By Colorado Review Assistant Managing Editor Jess Turner

Three weeks before I moved from Pittsburgh, when I was in the middle of taking a shower, the sink faucet turned on by itself. The water—full blast and intentional. I’ve always believed in ghosts (energies, spirits, entities, whatever you might call them). I almost exclusively listen to disturbing podcasts. I watch paranormal shows on television, the types that ask people who have encountered ghosts to recount their stories. All supposedly factual, or something like nonfiction in my mind (it’s okay, reader, if you don’t believe in ghosts, but bear with me).

I’ve had experiences before with the paranormal, but this time was different—some unknown entity waiting to announce its presence until I was at my most vulnerable. This got me thinking about vulnerability and horror in writing, especially as a woman. Naturally I first think of classic horror fiction: Dracula, Salem’s Lot, Frankenstein, Interview with the Vampire. And of course, there are dozens of memoirs written by psychic mediums and people who experienced their own hauntings. But I am a poet and—perhaps I am missing something—but where is the horror poetry?

After another incident in which the spirit knocked over my lotion bottle at 3:30 a.m., I decided to write a poem. I wrote it from the perspective of the spirit. This, for me, was a way to feel less vulnerable—to take on the voice of what was haunting me. I find that poetry too often is regarded as something rigid. One of the reasons that I was drawn to this genre is because I personally found it to be open, offering room to experiment. That being said, I think there is something so empowering about taking on the voice of something that “haunts” us, even it’s not a paranormal haunting.

So where are the horror poets? I know of Edgar Allan Poe, and I suppose one might include Emily Dickinson, but what I am seeking is something more nuanced. I don’t believe that we have to name “Death” in order to write horror poetry. I also don’t believe that horror poetry has to be truthful. You don’t need to be stalked by a ghost in order to write about being stalked by a ghost. You don’t have to be stalked by a ghost at all to write horror poetry.

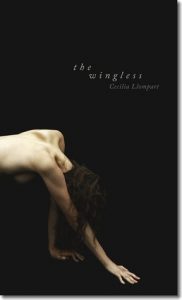

Regarding my own preferences, however, the horror poetry that I am looking for is more contemporary and less forward. In my research, I found a poem called “Omens” by Cecilia Llompart in which she begins:

The dead bird, color of a bruise,

and smaller than an eye

swollen shut,

is king among omens.

Who can blame the ants for feasting?

Let him cast the first crumb.

~

We once tended the oracles.

Now we rely on a photograph

a fingerprint

a hand we never saw

coming.

Llompart uses classic horror tropes—the omen, the oracle, the dead animal—to communicate a sense of loss and nostalgia. She sets the tone, taking these inherently cliché tropes and making them poetry.

Though it is not strictly poetry, in Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado does something similar. In this collection of dystopian, feminist, horror short stories, Machado uses poetic language (careful attention to sound, diction, and imagery) and reclaims horror tropes, usually reserved for men who dominate in the general field of horror. So while I wish for horror poetry, I also wish for women to be welcomed into the horror field across genres.

Earlier, I mentioned vulnerability and horror. A woman’s role in horror writing of any genre is most often the victim. Horror poetry, amongst other horror genres, could give women a space to transform from their stereotypical role as victim to writer. As the writer holding power, women might offer alternative representations of women within the actual content or use their power to communicate their powerlessness.

So why horror poetry? Partly for selfish reasons—it’s what I’m interested in right now, and therefore, what I want to read and perhaps write. Moreover it’s (mostly) uncharted territory, especially from women who can use this to their advantage, to change their common representations and experience all the usual relief that comes with writing a poem.

Plus after I wrote my poem, the ghost stopped coming around.