by Lincoln Greenhaw, Colorado Review Associate Editor

Picture yourself in a busy coffee shop with a copper counter and a ceiling festooned with strings of large, old-fashioned lightbulbs. There is dark, atmospheric music playing. Now take a moment to look around the room and listen as the various conversations about marketing plans or Internet cats wash over the dull bass of the shop’s indie rock station. The noise is huge and hydra-like, each voice containing music or commenting upon it, a word spoken differently each time that word is repeated. Words are a kind of music, but the implied song in them is limited by the need for words to remain linguistically meaningful. This constant push-and-pull between music and linguistic sense is the maddening heart of the strange experience that is poetry.

A poem is a kind of musical notation that doesn’t always translate to an aural performance. Often, a poem remains on the page to be pondered silently and repeatedly, unspoken except in the attentive mind.

The experience of music, though, is a very different thing. It can be loud to an extent, and part of its noise is of a more elemental nature, pre-linguistic but deeply communicative. While these pre-linguistic aspects of music create a context for any word uttered within that context, poems are usually made up of words and quiet—whether that quiet is the whiteness of a page or simply a pause for breath. In performance, lyrics are often like pages blowing about in a downtown wind: They make obscure forces apparent. In the process of reading a poem silently, there is only the voice in the reader’s mind blowing the words around.

It is, of course, difficult to speak accurately about concepts as fluid as “poetry” or “lyrics.” But I want to highlight one particular poet’s concerns set against the subtly different work of writing and performing songs.

Many readers criticize contemporary poetry for its difficulty—and it can definitely be inscrutable at times—but defenders of difficult poetry point to the fact that any hope of comprehending, say, a formidable painting or sculpture on the first viewing would seem very unlikely to an art lover. “Why should poetry be different?” they might ask. It is a quiet music that reveals itself with repeated study.

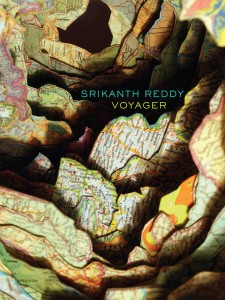

Take, for example, the poetry of Srikanth Reddy. His collection Voyager is a poetic erasure of the memoir by Kurt Waldheim, a former UN Secretary General who was later discovered to have been an officer in Hitler’s SS. It is Waldheim’s voice that was recorded speaking for humanity on the gold record aboard the Voyager space probe. This book is alive with layers of meaning, which reveal themselves further upon repeated readings. The very first poem is a good example of the project’s tone:

The world is the world.

To deny it is to break with reason.

Nevertheless it would be reasonable to question the affair.

The speaker studies the world to determine the extent of his troubles.

He studies the night overhead.

He says therefore.

He says venerable art.

To believe in the world, a person has to quit thinking.

The dead do not cease in the grave.

The world is water falling on stone.

Each poem’s voice is both Waldheim’s and Reddy’s. Waldheim speaks through Reddy’s repurposing of his memoir’s sentences. But the voice is also our collective voice, the voice of the human project on a golden record floating through space. Some lines can be read in the light of the memoir for which they were composed, but those lines gain meanings and ironies that are not at first apparent. “The dead do not cease in the grave.” They speak through us; our minds reanimate their words.

Each poem’s voice is both Waldheim’s and Reddy’s. Waldheim speaks through Reddy’s repurposing of his memoir’s sentences. But the voice is also our collective voice, the voice of the human project on a golden record floating through space. Some lines can be read in the light of the memoir for which they were composed, but those lines gain meanings and ironies that are not at first apparent. “The dead do not cease in the grave.” They speak through us; our minds reanimate their words.

Many poems function by implying music, implying world. Poems are not generally something you listen to in the background while washing the dishes. They tend to demand a constant attention. Poetry is a work in which the form is allowed to comment upon the subject of that work, and, in order to understand how the form might be operating, it is sometimes necessary to study it intensely. To echo Reddy, we must study such forms to “determine the extent” to which they present our troubles to us. But “the world is water falling on stone.” To study the world is to study an image in motion.

In a sense, every single lyric to a song is a moving image, a traversal of the voice that sways underneath it. The voice can convey an enthusiasm or gloom that might not seem warranted by the lyrics themselves. And lyrics can be set against the underlying emotion of a song, or they can be used to further articulate that emotion.

While poems are works in which the structural form is allowed to comment upon the subject of the work, songs allow the voice to comment upon the form. A person might read a poem in a sarcastic tone of voice, and that would obviously change the audience’s experience of the poem. A poem’s ironic tone might also mark a healthy awareness of the incompleteness of any literary experiment. The bafflement that many readers face when encountering contemporary poetry could be due in part to the lack of tonal or rhythmic guidance. A poet’s “voice” is often a silent form taken apart on the page, deconstructed by the poet in order to cast new light on a poem. Thus, finding out whether or not we like a poem just takes a lot of work. Our own voice is given wide latitude in reading them.

It is easy to contrast these concerns with the work of John Darnielle, the singer-songwriter for the acoustic-rock band the Mountain Goats. Darnielle is one of the best lyricists working today, and as the fiery, vocal engine of the Mountain Goats, Darnielle has secured a large audience for his literary lyrics. He is most widely known for “No Children,” a dark song about divorce, in which he gleefully sings these lines:

I hope that our few remaining friends

Give up on trying to save us

I hope we come up with a fail-safe plot

To piss off the dumb few that forgave us

The song is a paean to the terrifying, emotional abandon that often gains force throughout an unhealthy relationship’s dissolution. The tone is victorious, almost happy about the relationship’s destruction, and it lends a sense of the absurd to the song while remaining emotionally realistic.

The song is a paean to the terrifying, emotional abandon that often gains force throughout an unhealthy relationship’s dissolution. The tone is victorious, almost happy about the relationship’s destruction, and it lends a sense of the absurd to the song while remaining emotionally realistic.

“Riches and Wonders” is another great piece of work. It’s a much quieter song, and Darnielle’s voice maintains an even tone of earnest reflectiveness throughout the song despite the intensity of the sentiments carried though it. These are some of my favorite lines:

we write letters to each other

invent secrets to confess to

I learn foreign and exotic terms of

endearment by which to address you

we feed fresh fruit to one another

we stay up all night

and I am healthy, I am whole

but I have poor impulse control

and I want to go home

but I am home

Lyrics like “I am healthy, I am whole/but I have poor impulse control” hint at comedy, but the next lines display deep emotion: “and I want to go home/but I am home.” These last lines situate the intensity of a deep relationship in the ambivalence that accompanies any serious commitment. The song is rendered as the singer singing delicately to himself. Often, in moments of emotional exploration, we want nothing more than a clear, actionable explanation of our story so far, no matter how much such clarity implies deeper complication. Sometimes the earnest tone of a well-delivered lyric is enough to convey this by pointing to the sense beneath the words.

Often, lyrics in popular music explore the depths of a platitude. (Lou Reed’s song “Perfect Day” is a prime example this.) But as David Foster Wallace reminds us in his Kenyon College commencement speech, platitudes are not always bad things. “The fact is,” Wallace writes, “that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance.”

With that in mind, it seems to me that contemporary poetry might have a slight realization problem. Throughout my life, I have often had to hear the same platitudes over and over before realizing their importance. Anyone who has ever tried to express a consequential emotion to a significant other has some idea of the need for sheer repetition involved. The relationship between readers and poets might not be so different from a romantic relationship in this respect. Communication takes commitment and lends itself to variety. Good writers remember that simple statements are not necessarily easy to comprehend.

While writing poems, I try to keep voice and melody in mind as ways to present the pre-linguistic music that informs each line. And in the midst of inevitable, verbal complications, I believe there will always be room for a sincere word uttered tenderly.

Lincoln Greenhaw is a guitar player and lyricist for The Aquatic Lights, a band based in Fort Collins, Colorado. He is also a poet in Colorado State University’s MFA program.