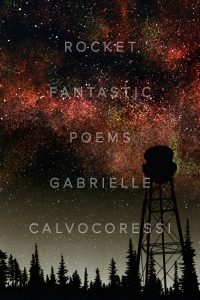

Book Review

The first poem in Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s Rocket Fantastic is called “Shave.” I read it once, and then again. I didn’t need to reread the poem because I struggled with comprehension; rather, I wanted to understand how the author had persuaded me to accept, so effortlessly, the unlikely combination of elements that come together in the poem. As the title suggests, it is a poem about shaving. The individual who shaves “was a lady once,” but now is a deer, a buck, in a forest. As this buck shaves, all the former shame of facial hair disappears. Now “the fox offers me the squirrel’s / hide to buff myself to shining.” All this I accepted with pleasure.

The first poem in Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s Rocket Fantastic is called “Shave.” I read it once, and then again. I didn’t need to reread the poem because I struggled with comprehension; rather, I wanted to understand how the author had persuaded me to accept, so effortlessly, the unlikely combination of elements that come together in the poem. As the title suggests, it is a poem about shaving. The individual who shaves “was a lady once,” but now is a deer, a buck, in a forest. As this buck shaves, all the former shame of facial hair disappears. Now “the fox offers me the squirrel’s / hide to buff myself to shining.” All this I accepted with pleasure.

There is magic in the poetry of Rocket Fantastic. Bodies are gendered and more-than-gendered. Humans are also creatures, most often a buck or a doe, who live and play amid other creatures of the wild. Then again, they enter the terrain of the archetypal, consorting with a queen or a hermit. The speaker’s lover is designated as “the Bandleader.” Why that title? I do not know. Do I really need to know? What I recognize in these poems is what I recognize from my daily life—we struggle to make sense of the world, we achieve moments of sense, even moments of ecstatic sensual surfeit, while at the same time the world crashes painfully around us. The leaps and syntheses of Calvocoressi’s poems understand this, all the deepest good and most corrosive bad and infuse the merging of unlikely elements with their own imaginative magic. Yet magic, here, somehow leads us beyond the speculative and into the real. Real—I’ll return to that in a moment.

I wonder if poetry isn’t always in some way a study of the nature of presence. Rocket Fantastic lives with the slipperiness of presence in multiple ways. Presence populates memory, and memory leaks—sometimes pollutes—the present with ghosts who disobey the boundaries of time. This is especially apparent in the poems that speak to familial relationships in Rocket Fantastic. The speaker’s father, in particular, is an ambivalent figure. At times, he seems playful and inviting, teaching his kids how to “get loose and double” and find the “null point:” a place in the visual field where opposing forces cancel each other out. Elsewhere in the book, the father is more malign, even cruel. In one prose poem section, the speaker, while still a child, refuses to keep walking during a demanding nocturnal hike and sits down. The father simply continues on and leaves the child alone outside overnight.

Later, the Bandleader tells the speaker, much in the vein of the father, “Let yourself get loose and double.” The Bandleader, a figure of intimacy and passion in these poems, briefly merges with the father. Obviously, lover and father are distinct—just as the speaker shaving in the first poem is clearly not a buck in the woods—and yet the blurring of identities is productive in these poems. We do imagine ourselves in implausible ways, and we do collapse one person into another in patterns of association that we cannot always understand—Why is it that I always want to call my younger brother by my older son’s name? These suffusions are part of the real to which I alluded before. Reality is constantly collecting its adjunct surreality and hauling it along into the actual. Calvocoressi is adept at getting loose and double where the past and the present soak through each other, and the null point is the site where we encounter the simultaneous, the whole of who we really are: “We were one / / in our wondering.” You could say that this is a new (renewing) mode of confessionalism that relates what happened and, on a wholly other plane, a just-as-real reality that didn’t happen.

You could say that Calvocoressi is audacious. She takes risks, and they work. But she is also graceful and not showy. There are things in these poems that don’t quite make sense to me—why the lover is called the Bandleader, why the book is called Rocket Fantastic. In the end, I accepted these elements as expressive eccentricity. They live in the poems because they live in the author’s mind—again: presence. Again: the real, or the author’s compelling animation thereof. There’s plenty here that instills trust because Calvocoressi is willing to reveal vulnerability, eros, pain, love. Here is the awkward child who cannot climb stairs, the niece whom an aunt finds rather distasteful. Here is the naked adult body spreadeagled in a window in flagrante delicto.

Presence, magic, and reality also intermingle to address the nature of the gendered or extra-gendered body in Rocket Fantastic. In the introduction, Calvocoressi explains that the character of the Bandleader will not be designated with a conventional binary pronoun, but instead with a symbol that I cannot replicate, called the dal segno. This “represents a confluence of genders in varying degrees, not either/or nor necessarily both in equal measure,” but rather an entity that is “encompassing and fluctuating . . . when a body is unlimited in its possibilities.” Once again, Calvocoressi shows us a reality that steps outside the known. I like almost as much the way the poems frame this symbol with another pronoun, “whose,” as in:

I count seven

stars between whose shoulder

blades and three inside

whose navel. And in whose eyes

I see nothing, they are so

dark they refuse whatever

light I offer. And yet.

It feels apt and right that a pronoun meant to convey such intimacy is also indeterminate and carries something of the interrogative—whose? The Bandleader, Calvocoressi tells us, “is indicative / of nothing or everything // depending on the day.” Herein lies the problem of the real—it is elusive, just as intimacy is. Experience marks us with pain and betrayal, but it also enables us to realize a body somehow unlimited in its possibilities.

Reading Rocket Fantastic effects transformations that the reader has always suspected were possible without denying the wounds that continue to accrue in the past and present, in intimacy and the polis. To embrace what cannot be entirely known is a form of magic. Magic abounds here and suffuses fact with new sense.

About the Reviewer

Elizabeth Robinson’s most recent books of poetry are Blue Heron (Center for Literary Publishing) and Rumor (Parlor Press/Free Verse Editions). Vulnerability Index is forthcoming from Ahsahta Press in 2019. With Jennifer Phelps, Robinson coedited Quo Anima: innovation and spirituality in contemporary women’s writing, forthcoming from University of Akron Press.