Book Review

In the 1944 film To Have and Have Not, Lauren Bacall delivers what might be her most famous line (in her first movie, at that). After kissing Humphrey Bogart’s character for the first time, as she’s exiting the room, Bacall’s Slim says:

In the 1944 film To Have and Have Not, Lauren Bacall delivers what might be her most famous line (in her first movie, at that). After kissing Humphrey Bogart’s character for the first time, as she’s exiting the room, Bacall’s Slim says:

You know you don’t have to act with me, Steve. You don’t have to say anything, and you don’t have to do anything. Not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle. You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and . . . blow.

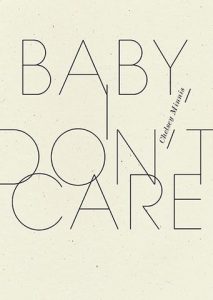

The final line is delivered wonderfully by Bacall. She smirks as she says it, and after pausing before “blow,” immediately leaves the room. The audience, like Bogart’s character, is left smiling goofily and blinking. This seems an appropriate place to begin a review of Chesley Minnis’s Baby, I Don’t Care, a book concerned with suggestion, affect, and great endings.

Moreover, in Baby, I Don’t Care’s acknowledgments, Minnis notes that the “book was inspired by classic movies and couldn’t have been written without the Turner Classic Movie channel,” and the book indeed sounds more like a classic movie, specifically classic film noir, than any book of poetry I can think of. The book appropriates the language and feel of old movies to a remarkable degree. For example, the word darling appears sixty-six times across the book, while baby shows up thirty-one times; who says darling anymore? And it’s easy to imagine Baby, I Don’t Care’s speaker delivering many of her lines over her shoulder, while wearing a mink stole, cigarette in cigarette holder. Here’s what that looks like in practice. This is from “Larceny”:

You have a pretty low opinion of me, haven’t you?

I did something wrong, once.

Oh, but that was years ago.

Don’t get sentimental, darling.

What’s new in the world of slander?

If you love me baby, tell me about it.

It’s charming when you lecture me sternly.

Darling, the ice would melt in my veins.

You and your diamonds.

Anytime I want anything from you I’ll take it.

Baby, I Don’t Care is poetry to read while having cocktails, or vice versa. Baby, I Don’t Care is the book a bored suspect turns to while the detective determines who killed the dinner party guest. Baby, I Don’t Care should replace Gideon’s Bible in casino hotels. Baby, I Don’t Care would make great reading after a night of film noir and absinthe. All of which I mean as praise.

Minnis’s fourth book, Baby, I Don’t Care follows Zirconia, Bad Bad (published in 2001 and 2007, respectively, by Fence Books), and Poemland (2009, Wave), and is the most refined, clearest distillation of her unique voice—droll, darkly comedic, self-loathing, unconvincingly debonair—so far. Per Robert Strong’s blurb on my copy of Bad Bad, “her poems take some getting used to . . . .” But if you’re used to Chelsey Minnis’s poetry by now, then you’ll love Baby, I Don’t Care. And even if this book is your introduction to her work, it’s a good place to start.

In part because Baby, I Don’t Care lacks the ostentatiously avant-garde tendencies shown in Bad Bad and Zirconia. Gone are the run-on periods, wacky fonts, and symbols that typify her Fence work. Indeed, even Poemland’s habit of ending lines and poems with ellipses or exclamation points has largely disappeared. Instead, the work in Baby, I Don’t Care is almost staid by comparison; the poems are recognizably poems, with stanzas, caesuras, and end stops. There are even titles.

Which is not to say the writing itself is staid. Hardly. As shown above, Baby, I Don’t Care is a crackerjack book brimming with vim and character. It’s also very recognizably a Minnis book. Compare these two untitled poems from Poemland and Baby, I Don’t Care:

From Poemland:

If you want to be a poem-writer then I don’t know why . . .

It hurts like a puff sleeve dress on a child prostitute

Nothing makes it very true . . .

Except the promised sincerity of death!

From Baby, I Don’t Care (from “Laziness”):

First of all, do you have any money?

Sometimes I feel a slight warmth about money.

Baby, I might not be any good!

The only thing I do is write down words.

I make it special though, don’t I?

I wonder about things, but not too much!

You must understand the great laziness.

And don’t you feel colossal?

Forget about the math, baby.

By all means, let’s get drunk in a bar with a coat of arms on the sign.

Aside from the formal differences between the two poems, the work from Baby, I Don’t Care is slightly less dark (I mean, a “puff sleeve dress on a child prostitute”? Oof.) and somewhat funnier; it is as impish a book of poetry I’ve read since the last book of Minnis’s I read. Here Minnis re-establishes herself as perhaps our best, most biting, black-comic poet. Her poems sting.

Because I can’t help myself, here’s a final particularly wry excerpt from “Iceberg.” I highly suggest reading the whole book, as it’s a singularly immersive experience. That may lead to increased usage of darling, darling:

It makes me jump into the fountain.

It makes me crack up inside, it really does.

You’re handsome, but you don’t give me anything that I can use.

Let’s have drinks in my room after church.

I love you or words to that effect.

Shall I go or wait long enough to get my face slapped?

It won’t be a new sensation.

I wonder what the nice people are doing tonight.

You think I’m beaten, don’t you?

Well, I still can lose money.

About the Reviewer

Originally from Philadelphia, Kevin O’Rourke lives in Seattle, where he works in book publishing. He studied art at Kenyon College and writing at the University of Minnesota. His first book, the essay collection As If Seen at an Angle, was published by Tinderbox Editions. He is an active book and cultural critic, and his writing is currently supported by a grant from 4Culture.