Book Review

Brenda Hillman’s tenth book of poetry, Extra Hidden Life, among the Days, is an eclectic collection grounded in the materiality of nature and the fact of writing. Hillman plays with the post-human—a hypothetical, ecological state following the extinction of humanity—but never abandons political activism and poetic optimism. In fact, although the collection contains two lengthy sections dedicated to the poet’s recently deceased father and to the poet C. D. Wright (deceased in early 2016), Hillman’s poems are almost startlingly optimistic. Although the collection squarely faces (and opposes) humanity’s staggeringly negative effect on global ecosystems and the contemporary American political moment, Hillman’s poems do not retreat into wary irony or apocalyptic destructiveness. The collection brings this optimism to the contemporary political and ecological moment as an act of both political resistance and poetic creation.

Writing, always separated from speech, is one of the central operative metaphors of the book. For Hillman, the act and presence of writing allows the human and so-called natural world a point of contact, although, as she indicates in a series of moving poems about environmentalist John Muir, the concept of nature is as constructed as any other anthropocentric idea. Yet the word “nature” and the corresponding concept are irreplaceable in our modern lexicon—a Romantic problem in which we have caught ourselves, as poets and humans. Nothing is genuinely outside of nature. As Hillman eloquently puts it in “The Bride Tree Lives Three Times,”

some like to avoid the word nature

but what to put in its place. . . .

When you are confused about poetry

& misunderstand its brown math,

the sessile branches & a seal of awe

attach the tree to the dark.

Someday, you’ll need less evidence;

the missing won’t cease to exist.

Amid sections lamenting the current state of American politics and praising day-to-day political activism, Hillman reminds us that we have no idea what nature thinks of itself or how it would act outside of the aggressive machinations of late capitalism. With tongue in cheek, she writes: “There was aggression among large mammals / but no merrill lynching, no goldman saching, / no bankers’ greed or quantitative easing.”

So for Hillman, the baselines, the ground floors of commonality between the human and the natural are the act and the form of writing. The pure physicality of the act of writing is not limited to humanity and is not necessarily tied to a conscious mind. Poems blend human compositional agency with natural phenomena (itself a type of pseudo-agency) to decenter the human will and enfold it within a natural system of writing-deployment. In the poem “Composition: Under Cypresses, Near Big Sur,” Hillman ties her own writing to the sounds and sky-shapes of circling crows. She writes:

facing the full-of-plastic Pacific, eager to include crows,

. . . i’ve thought punctuation has features of skylight . . .

. . . hoping this might lift the dread of being human, & early, relieved by dots in the air,

i repeated a composition 6 times with the crow & tried to breathe humanly . . .

The poem aligns the forms and actions of human and natural through the material shape of punctuation and acts of (pseudo)writing. In the human-natural-political assemblage that Hillman creates, no agent dominates or suppresses any other, whether animal, vegetable, or mineral. The horizontal, the truly democratic, prevails.

In “A Poem for a National Forest,” one of the most effective sections of the book, Hillman illustrates this horizontal writing aesthetic by comparing the writing of a poem with the “writing” of beetles as they carve abstract paths and tunnels beneath the bark of trees. On each page of this section, following the last line of the poem, Hillman includes a small photograph of a single, twisted, semantically impenetrable segment of beetle “writing.” She articulates that the human poet and the beetle perform acts of staggering similarity, despite the utter illegibility of the beetle’s script. Hillman narrows the gap between “human” and “natural” work, and reminds us that the formal creative processes of nature are only a shade different from our own. In part “d.” of this sequence (“the writing between forest & mountains”), Hillman writes:

. . . beetles

chew

the trees, meaning by erasure, prefixes,

syllables,

inventing humped letters not in English . . .

& today I have fallen in love

with the borers & the sawyers

writing in the cones

with larval forms of the obtuse

for they love wood as I love paper,

pressing

their whole jeweled bodies

into the beauty of the bark, dark bark,

sexy sexy sexy abstract beauty—.

The form of poetry (and writing-in-nature) also carries meaning. For Hillman, metaphor and simile (among other formal devices) are not limited to poetic creation but allow us ways to interpret nature, humanity, politics, and death as extensions of form. The optimism that comes from writing allows Hillman to conjoin the human, the natural, the political, and the personal in ways that form a democratic assemblage out of registers of life that are often considered to be opposing binaries. Hillman uses optimism-through-writing to dismiss neither the human nor the human’s daily life (which includes political fury and the sorrow of bereavement) but to permeate and redefine what we mean by human and nonhuman life.

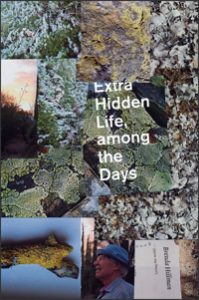

Extra Hidden Life, among the Days is saturated with objects and shows a sharply intelligent curiosity toward the object world at macro- and microscopic levels. Hope emerges from this materially focused fascination with objects. Hillman’s hope, an aspect of her optimism, seems to stem from an inclination to focus on the overlooked or unnoticed aspects of relationships, poetry, and nature in order to unearth, reclaim, and reincorporate the once-dismissed aspects of our (political) reality into dominant discourses. This poetic choice is another form of democracy, of aesthetic horizontalization. Another profoundly effective section of the collection, “Metaphor & Simile,” features a small photograph of lichen on every page. The visual inclusion of lichen, itself often confused (as Hillman notes) for moss, allows a marginal organism substantial space on the page. Moreover, Hillman implicitly gestures to lichen’s tenacity and its slowness to grow as it spreads its text-like tendrils across the surface of impassive stone. She writes in “Day 1,” “greenshield / lichen. . . . Indicator / species. Indicators of health, in the twilight / of a terrible year. . . .” Lichen hones in the focus of both reader and poet to the nearly passive, script-like presence of a nonhuman, ecological way of grappling with what the world itself, in all its withdrawn profundity, means.

Hillman’s collection gestures to curiosity, openness, and an engagement with the materiality that surrounds her (lichen, beetles, crows, plastic bags, driveways, fast food, molecules of every variety, trees, otters, and bacteria). Furthermore, it gestures to an overlap of knowledge and creativity between the “human” and “natural” worlds. As she writes in section “g.” of “Poem for a National Forest,” “Each small section of the world is / owned / But meaning is not owned.”

About the Reviewer

Connor Fisher lives in Athens, Georgia. He has an MA in English literature from the University of Denver, an MFA in creative writing from the University of Colorado at Boulder, and is working toward a PhD in English and creative writing at the University of Georgia. Reviews and poetry have appeared in journals including Word for/Word, Typo, the Colorado Review, 7x7, and the Volta. His chapbook The Hinge is available now from Epigraph Magazine.