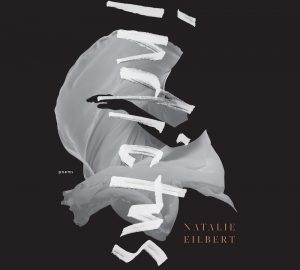

Book Review

Indictus, the Latin word for what is unsaid or unheard, points in many ways to the great silence each poet must face. The silences in poetry are as important as the words, the spaces as moving as the lines; the lyric “I” speaks to and against this. And yet what has wrought more damage than the silences (and silencing) of trauma in cultural discourse? In Indictus, Natalie Eilbert verbs the titular root word into “indict” and “indicate,” naming the traumas committed against the female body in a document that can never truly be finished. Writing generally in lengthy poems across several parts, Eilbert resists the neat formal unity of single-page poems, suggesting that trauma similarly resists such unity and resolution. The speaker in the forty-four-page poem “Man Hole” meditates on how language means that trauma is never neatly sealed into the past, nor into a fixed shape:

If language is required to give what happened narrative context, then

the past is not the past at all but always present, in the way glass is

liquid. We do as glass does, pretend solidity by breaking down over

time. How can we know any better?

How indeed can we know any better than to pretend in our cultural discourse that the past is past, that sexual violence is over and done with for survivors? Eilbert offers an alternative, holding open the wound by concretizing the spaces left by trauma and the shape a telling makes around the traumatic act. Mouths and holes become slippery sites of agency and removal of that agency. Men are destroyed but must be reconstructed to retell the story of violence. The language taken from the body by men is returned, as in the poem “To Read Poems Is to Follow Another Line to the Afterlife. To Write Them Is to Wed Life with Afterlife”: “I push language back into the body I could never save—and I pull from the hole a roster.”

Forming men “into the wound of a line,” Eilbert works to reclaim language without letting its discourse simply recapitulate the trauma. As the title of the poem indicates, writing a poem becomes an act of radical ethics and radical fusion—life to afterlife, before to after, light to shadow. To tell what happened is to join two wholly separate realms, a mythic transgression that welds time with consecration, but not necessarily consolation.

Such an ethics, combined with startling imagery, evokes Plath in depictions of female speakers reclaiming power and reenacting wounds on men. Like Plath’s “Lady Lazarus” who rises “with [her] red hair” to “eat men like air,” Eilbert’s speaker in “Man Hole” declares, “I blast holes in the pits of the men,” and “I am a bright red wet mouth that lies to everyone.”

And yet, Eilbert’s ethics of shedding light on the reciprocity of trauma also shares concerns with Simone Weil, whose words appear in “Man Hole”: “A hurtful act is the transference to others of the degradation which we bear in ourselves.” The poems in Indictus may indict wrongdoers and offer a space for survival, but they also suggest that we hurt one another because we hurt ourselves. The speaker of the poem “Testament with Water under the Bridge” evokes this reciprocity in the formal duality of couplets and images of harm to the self:

of refusal: to know I am rent and crave the chasm that it makes.

Yes I excited the scene in a powerful gown, but when the sun

sets we fail each other. It is religious, my desire to find a better bridge . . .

The craving for chasm can refer to both the wound inflicted upon the self by the self and the wound inflicted by the assailant; it can indicate both the original harm all people commit against themselves, leading them to hurt others, and the long-standing effects of those wounds: a craving for the hurt. Even if reciprocity involves a level of reclaiming power—a gown, an outward symbol declaring status—all power, and the way we inflict it on each other, is implicated in failure. These are the difficult lessons with which Eilbert grapples, making room for the complexities of interpersonal violence.

In finding language to articulate such a poetics, Eilbert uses the sentence as a unit, sometimes breaking into lines and sometimes using the prose poem stanza as a way to quite literally sentence the men. The speaker calls our attention to these prosaic qualities in “To Read Poems Is to Follow Another Line to the Afterlife. To Write Them Is to Wed Life with Afterlife,” claiming them as power: “Let me say of language that it is my currency and it performs best when it is stripped of decorum.”

The prose poem format is a way of sometimes removing this decorum, which then gives way to lines that hold all the more incantatory power for appearing after sentences that stretch clear from one margin to the other. In the short poem “Neighborhood,” the lines take on the quality of fairytale or myth, their images of woods and indention waving back and forth across the page like a series of slow, deliberate steps down a path:

I was a boy until they found me

lost in the woods. Then I was just

a stupid girl lost in the woods.

With their use of pacing, the lines hold the decorum otherwise absent in the prose, which is a part of their woundedness and a part of their necessity to the indictment that Indictus makes.

With a book that revolves around holes and fraught relationships, Eilbert also troubles the lyric “I” and the traditional relationship between the “I/thou” of love poetry. In “Man Hole,” the speaker responds to a “you” dismissing her life as a “sob story” by transforming the personal pronoun first into an object, then almost a verb: “I give my I a new look. I rosy cheeks.” This “I” becomes simultaneously filled and emptied, a stripped pronoun that seems at times loaded with autobiographical detail persisting across sections and poems, and at other times seems slippery, transformative, like Lady Lazarus tearing away layers. The “you” is the oppressor, is the victim, is nonexistent, is the reader; the “thou” that love poetry so often addresses, some beloved, becomes an ambiguous verb in “Man Hole”: “I thou him so hard I feel his fingers wrapping their worth round my neck.” “Thou” thus becomes an act of lovemaking or an act of violence, or both, and another instance of grammar being transformed through an act of agency on the part of the speaker.

Such dichotomies of language ultimately encapsulate the beautiful paradoxes at the heart of Indictus: language is used as a weapon to both remove agency and reclaim it, an indictment reifies the trauma as it names the crime, and what is unsaid must be both named and somehow left unsaid. As a result, Eilbert speaks beautifully and urgently to the silences that persist in our discourse and the stories survivors tell in the face of power that exists at every level of language, including poetic register. Reading Indictus is a line to the afterlife and a challenge to refuse complicity. Writing after Indictus is a way to keep caring, to keep digging, to keep verbing.

About the Reviewer

Kelly Weber is the author of the chapbook All My Valentine’s Days Are Weird from Pseudo Poseur Press, and her poems and essays have appeared in Upstreet, the Midwest Quarterly, Nebraska Poetry: A Sesquicentennial Anthology, and elsewhere. Her work has been nominated for the AWP Intro Journal Award, and she has served as an artist-in-residence at Cedar Point Biological Station. She is currently an MFA candidate at Colorado State University.