Book Review

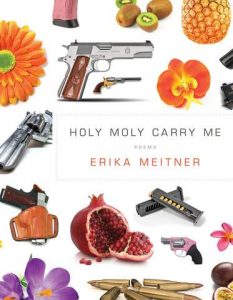

In its explorations of citizenship and everyday life, Erika Meitner’s fifth collection of poems, Holy Moly Carry Me, is filled with worry. And why shouldn’t it be? On television, there are more school shootings. The girl selling Thin Mints door-to-door is wearing a uniform vaguely reminiscent of Hitler Youth. History is unsettling and so is the present (“This year / has dragged like / a broken tailpipe”). And while many of Meitner’s meditations are brutal and anxiety-laced, what’s also clear is this collection believes firmly in the power of goodness. The world is dangerous, but not all hope is lost: It can be immeasurably beautiful, too.

The book opens with “HolyMolyLand,” a sprawling poem covering everything from Captain Marvel and thrash metal to Moses and Marco Rubio. “In The Odyssey,” the poem begins, “there’s mention of a plant called moly, which is sacred and harvested only by the gods. // The gods are vengeful but they are also good to us, though we have given up sacrifices and burnt offerings.” From the get-go, Meitner studies how divinity crosses—or fails to cross—into our everyday lives. The poem takes a panoramic shot of societies through time and space and asks what is holy and within our reach? How is faith ultimately linked to our realities? The poem is an encyclopedic study of humility, and it catapults us into the present moment to question what is divine and what is moral right now.

As a result, the rest of the collection is very much rooted in life in 2018: It’s filled with references to LeBron James, Dumbledore, hashtags, and Bud Light Lime. Meitner holds up these details and studies how gorgeous the ordinary can be if you look close enough, as in “Your Body, Your Margins, Your Diminutive Villages,” which reads:

. . . but today

outside the automatic doors by the

caged propane tanks and water dispenser

and Red Box movies and Coke machine

there’s a two-tiered metal stand with hanging

baskets of trailing pansies on the bottom

shadowed by wind chimes with miniature

pastel birdhouses on top and what I want

to tell you is that these stop me: their song

and their otherworldly new age light

speaking at the top of their lungs . . .

These are the spaces in which our own myths are made: tiny, ordinary spaces filled with random babble and clutter. In several poems, these moments are further enhanced by pairing the everyday details with more traditional and historical references (various psalms, the Secret Annex, Monet, etc.) to study beauty across time. In Meitner’s hands, just about anything can be an artifact of biblical proportions.

One of the collection’s central (and most powerful) obsessions is children and, specifically, the threat of their absence. Here and there, poems allude to the speaker’s infertility and determination to have a family no matter what. At times, this longing weighs heavily on the speaker (“Maybe I had nothing to offer. / Maybe I didn’t promise enough, weep // enough, open my palms wide enough . . . ”), but this is only part of the story. Once children enter the picture, there is the fear of losing them. A handful of poems directly confront the epidemic of gun violence in the country and how children—at school or out in the world—are vulnerable. In “Continuation,” Meitner writes:

Sarah’s mother threw her father out

for keeping a loaded Uzi on the floor

of their garage. When Sarah aims,

with her fingers, at the empty birds’ nests

in the eaves of our porch, I wait for her

to say bang, but instead she repeats,

It had bullets in it . . .

With these astonishing lines, Meitner investigates our relationships (and our children’s relationships) to firearms: We’re used to kids wielding make-believe guns, but what happens when the consequences feel too close, too real? How to protect them from harm when it seems to be everywhere?

Part of the collection’s magnetism is this emphasis on compassion and protection. Almost every poem gets political—addressing issues like gun violence, systemic racism, outrage over teacher salaries, and religious persecution—but it never feels preachy; rather, it reads as someone you wholly trust telling you, matter-of-factly, how it is. There is a sincerity that is not only compelling but also affecting. In “Jackhammering Limestone,” a poem in which the speaker tries to imagine a bright future, Meitner writes, “More like I would invent a future where my black son will not // get shot by police for playing in a park, or driving, or walking from his / broken-down car.” Ultimately, Holy Moly Carry Me functions as a political collection, but it isn’t bogged down by that angle. Instead, it remains beautiful, heartfelt, and playful at once, bringing the work of C. D. Wright to mind.

And while this collection examines these very serious subjects, Meitner’s tremendous wit and sense of humor shines through and is expertly deployed. “Bless the black G-string, / abandoned on the sidewalk” begins “Post-Game-Day Blessing,” a poem taking inventory of the messy aftermath of a college town reveling in a home victory. Even in this scene—littered with red Solo cups and condom wrappers—Meitner is capable of revealing something urgent and exciting about motherhood and the state of the world, proving that what is messy can be fun, and what is fun can still feel dangerous.

With Holy Moly Carry Me, Erika Meitner has written a collection we very much need in 2018. “If you are fearful, America, / I can tell you I am too,” she writes in “I’ll Remember You as You Were, Not as What You’ll Become,” the final poem of the book. And at the end of the day, much of this collection is about these intersections of public and private spaces. We see the world’s terrors and must digest them to keep ourselves moving forward. It’s depressing. It’s terrifying. Still, there are hints of hope in the little moments: how the bag boy rides shopping carts in the Food Lion parking lot; the ordinary magic of letting something go in the library’s drop box. Small things. The things we try to savor every day.

About the Reviewer

Rob Shapiro received an MFA from the University of Virginia, where he was awarded the Academy of American Poets Prize. His work has appeared in the Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Blackbird, and Prairie Schooner, where he was awarded the Edward Stanley Award. He lives in New York City.