Book Review

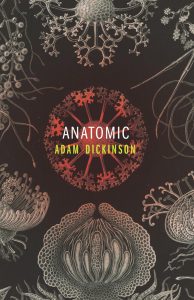

Anatomic, Dickinson’s fourth collection, is a partnership between both a science experiment and a book of poems. After having an impressive series of tests run on his body, Dickinson uses poetry as his laboratory notebook. The poems in Anatomic record data, suggest hypotheses, provide context for discoveries, and lay out the subject’s reflections.

Anatomic, Dickinson’s fourth collection, is a partnership between both a science experiment and a book of poems. After having an impressive series of tests run on his body, Dickinson uses poetry as his laboratory notebook. The poems in Anatomic record data, suggest hypotheses, provide context for discoveries, and lay out the subject’s reflections.

From the title poem, “Anatomic,” Dickinson gives some insight into these pursuits:

I wear multinational companies in my flesh. But I also wear symbiotic and parasitic relationships with countless nonhumans who insist for their own reasons on making me human. I want to know the stories of these chemicals, metals, and organisms that compose me. I am an event, a site within which the industrial powers and evolutionary pressures of my time come to write. I am a spectacular and horrifying crowd. How can I read me? How can I write me?

Dickinson doesn’t merely suggest that it would be interesting to think of cellular communication through the lens of crowd mentality; he demonstrates the idea over the nineteen-part poem, “Hormone.” Here, he achieves an unusual and fascinating way of thinking about “the big within the small.”

Within these cell-sized containers, the reader will be delighted to find explorations of the larger social landscapes that encompass politics, masculinity, and consumerism—all offered up by a contemplative, philosophical voice. In one passage of “Hormone” Dickinson writes:

Anxiety awaits

for a table

under a cave painting.

Water stirred

with a spear.

Keeping it together

is a form of digestion,

and digestion

is a form of commitment

to the dignity

of letting it go.

One part of you,

as an act of survival,

starts eating another part

This is a membranous

decision

in which the crowd,

having mistaken

its periphery, resembles

its prey.

It seems Dickinson expects a little more from readers—the level of scientific vocabulary used in the poetry isn’t quite laborious, but it does require a more engaged reading of the collection. Thankfully, he doesn’t completely leave the readers without guidance. He gives some additional insight into the “Hormone” poems with “Outside Inside” in which he also plays with the idea of the poem as a body. It begins:

Hormones have their own poetics. Secreted into the circulatory system in response to chemical signals, hormones write to distant organs. Their task is the prosody of the metabolism – cellular rhythms harvest energy from food and air to fuel digestion, reproduction, growth, and the general health of a body. This book of glands and hormones makes up the endocrine system, an enduring evolutionary adaptation that has changed little in millions of years.

The philosophical voice is a hallmark in Dickinson’s poems and spans beyond the “Hormone” pieces to fully shine in his prose poems, which could be considered hybrid forms, giving a nod to the flash essay or micro fiction. For instance, on page 83, in a sequence of poems titled “Disruptors,” Dickinson writes:

Having bravely stood in a javelin rain, the male brain turns a blow dryer on a friend’s stream of pee. Though it will never admit to this, the male brain is tense that its tense in the future perfect: what will have been the means by which it means? It squats in its skull like a cork.

In addition to introducing wonder and making suggestions, the voice doesn’t shy away from being declarative. “Circulation” demonstrates this:

Anxiety is a form of autoimmunity. You can’t be trusted with your own intentions. I wash my hands and then I think to wash my hands. This is an attempt at silence.

Too, in “Galactic Acid,” Dickinson declares: “For the first two years of my life, my mother’s vaginal flora lived in my stomach.” He ends the piece by offering:

I watch my mother favour her disintegrating hips. The small party that left her for the new world founded settlement on a moon she still tracks without looking. Its tidal pull on the pit of her stomach makes her pause at the zenith of a phone call: ‘What is it?’

Aside from the more traditionally recognizable poems, Dickinson includes asides that are formatted in a different font and act as supplements for the reader. On one hand, these provide practical information like the one on page 16: “I filled seventy-six vials of blood.” But they also act as in-depth context for some of the explorations in Dickinson’s poetry, such as the aside on page 66 that reads:

I’m a white male. My body is marked by certain demographic privileges. It is true that racism and economic marginalization can cause people to live in closer proximity to industrial pollution. It is also true that privilege, with its associated dietary and hygiene opportunities, can lead to a less diverse microbiome and increased incidence of gut infections.

At the end of the book, Dickinson provides full-color images and graphs of some of the data gathered throughout his project, as well as an image on page 141 of an erasure poem that was “edited and revised by bacteria cultured from swabs of money.” This collection is brave and multi-faceted in its approaches and subjects. All between two covers, Anatomic gives its reader a mini science lesson, wrestles with the world’s environmental and consumer issues, and finds refuge in a variety of poetic forms. This collection beckons for a reader that will spend time and return again, still hungry.

About the Reviewer

Sam Leon is an MFA candidate in poetry at Florida International University where she teaches undergraduate writing. She is the assistant managing editor for Gulf Stream Magazine and a coordinator for the Richard Blanco Fellowship. Her book reviews and author interviews can be found in Gulf Stream Magazine, Tupelo Quarterly, and the Iowa Review.