About the Feature

The Spirit Cabinet

Anthemion

Her grandparents had spoken “a foreign tongue,” she recalled, but she couldn’t say which one. When I pressed for more, my grandmother would grow glum and dour, as if she were resisting prosecution. I took a picture of her the last day I visited her apartment. Her cat is in the foreground on the kitchen table, and she’s in the background, looking down, unfocused, sad. She’s ninety years old but looks like a child. I loved my grandmother but was confused and frustrated by her silences (I was afraid of inheriting them). The next time we met, she was in the hospital, where the time for questions and photographs was over, for she was at the end of a rope of immense pain. Without saying goodbye, I fed her little ice pellets from a white, nearly weightless plastic spoon.

Burl

Walter Benjamin wrote that “history decays into images, not into stories.” He was fond of quoting Proust’s notion that “the souls of those whom we have lost are held captive in some . . . inanimate object, and so effectively lost to us until the day . . . when we happen to pass by the tree or to obtain possession of the object which forms their prison.” This is probably why, when my parents asked if I wanted the secretary, I said okay. The secretary is a piece of furniture purchased by my great-grandparents in a department store a hundred years ago. They were notoriously private people, which explains my grandmother’s privacy. As a child I always avoided the secretary, with its gloomy, sepulchral air. But my parents were winnowing their possessions, moving to California, so I accepted their offer to ship me the thing free of charge.

Cabriole

It arrived one morning in a large truck. Two Russian movers carried it through the front door, deft as undertakers, and set it down in the designated corner. With its finely grained mahogany veneer, it was handsome but moribund. A solemn columbarium, it had little drawers and dovecotes for sorting paper; one of the drawers could be lowered to reveal a writing surface (I wondered if anything had ever been written there). Then there were the thirteen boxes of books that came with it. As I began reshelving them, I couldn’t help recalling “Unpacking My Library,” in which Benjamin extolls the virtues of book collecting. Inheritance is the best way of acquiring a collection, he suggests, for “the most distinguished trait of a collection will always be its transmissibility.” What exactly was being transmitted I didn’t yet know as I handled the books, which had a genuine aura because the leather and paper smelled so old, but seemed fake since I wasn’t sure anyone had ever read them. Perhaps that’s my job. Secretary means “one in whom secrets are entrusted.”

Dos D’Ane

In modern times, a secretary is typically a woman who assists people with clerical and administrative work, takes dictation, etc. This describes me fairly well. I’m good at making myself invisible. I’ve always felt a special fondness for Ishmael, the “sub-sub librarian” who spends his later years, post-Pequod, burrowing in libraries, collecting allusions to whales, to whiteness, to the disaster he survived. These hundred books were someone’s idea of the Western canon. A biography of Cortés called History of the Conquest of Mexico. A biography of Napoleon. The memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Volumes by Shakespeare, Dante, Cervantes—books meant to prop up a peculiar social identity, whiteness, and a sense of being landed economically. And then I found an object that turned out not to be a book at all, but a small wooden safe in which one could conceal one’s tiniest treasure. Its spine read Sister Dolorosa—from dolor, meaning painful, sorrowful, grieving—and inside it was completely empty. I thought of Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. And how the Hebrew word for “to read” means to cry out . . .

Escutcheon

I had a theory about my family: They were Ashkenazi—the Marxes and the Friedmans had come from Hungary and Ukraine during the pogroms of the 1880s. But they had disavowed this legacy many years ago. My grandmother refused to admit that her grandparents spoke Yiddish. But I had done my research. When I mentioned this to my friend Jenna, who knows a lot about trauma studies, she recommended The Shell and the Kernel, by Nicolas Abraham. A Jewish psychoanalyst who survived the war in Hungary, Abraham had studied the effects of transgenerational secrecy. Secrets get passed down and filed inside us, he imagined, like letters whose envelopes have never been opened. These crypts are like “psychic enclaves” that the descendants of survivors install within themselves. “The crypt is there with its fine lock, but where is the key to open it?” Abraham asks in “Notes on the Phantom.” He died before he could flesh out a coherent theory. But in his notes he proposes some fanciful ideas. Secrets act like foreign presences hosted by the patient’s unconscious and express themselves only through aberrant ventriloquisms in which the representational character of language is subverted by the wild subterfuge of glossolalia. Secrecy “works like a ventriloquist,” he hazards, “like a stranger within the subject’s own mental topography.”

Flitch

For years I wrote poems that verged on nonsense, attempting to mimic the surrealism of Rimbaud or Ashbery. These days I’m trying to make sense of things more clearly. I want content. For instance, what does it really mean to confess “I is an other,” and what did Rimbaud mean when he explained this statement by saying, “Too bad for the wood which finds itself a violin”? I will try to find out by consulting the secretary, by writing in the manner of the secretary. Whenever I find a fragment that bears some flake of self-knowledge, some half note or broken twig, I will slip it into a dovecote or drawer for safekeeping.

Gadroon

When I was ten, my family went to see Broadway Danny Rose, the new Woody Allen film about a talent agent managing a bunch of washed-up, two-bit performers. I heard some whispering down the row at one point, then my mom leaned over and whispered, “That’s your uncle Herbie.” The character she was pointing to was a ventriloquist with a stutter that disappeared only when he spoke through his dummy. I had heard rumors about our uncle Herbie. He was, in real life, a struggling ventriloquist who played cruise ships and occasionally hotel gigs in the Catskills, and lived with his ninety-five-year-old mother in a Brooklyn walk-up. There was a way of chuckling at Herbie that suggested embarrassment and pity. Afterward everyone seemed a little ashamed that Herbie had outed himself so publicly like this. For he wasn’t just acting a part—he was playing himself in front of everyone. He was his own dummy.

Hassock

The email that arrived out of the blue informed me that the writer was my distant cousin, a couple times removed. Her name was Evelyn and she was eighty. She had pulmonary fibrosis and was in an assisted living facility outside of St. Louis. When I called the phone number she provided, she explained how she was trying to fill in all the leaves and branches of the family tree before she died. I said I knew almost nothing. She didn’t mind; she was happy just to connect and talked for most of the hour. We were related, she explained, through her father—Billy Finkelstein, the brother of my great-grandfather Louis. They had come over from Russia during the pogroms in 1882. Then at age twelve, Billy ran away from the orthodox Finkelstein family to join a traveling circus; he painted his face white and performed as a professional clown. Eventually, he made it to Hollywood and was hired as a double for Charlie Chaplin. Yes, he and Chaplin forged a lifelong friendship, and Billy died wearing a ring that Chaplin had inscribed to him. Evelyn sent me some clippings as proof the next day. In the March 27, 1937, edition of the Omaha Bee-News, there is a fuzzy photograph of Billy Finkle floating above the caption: “Chaplin’s double has appeared in all of Chaplin’s films but ‘Modern Times,’ and between movies makes personal appearances as Chaplin’s double and works circuses and theaters with a Chaplin act. In fact, Billy says, he and Chaplin photograph exactly alike.”

Inlay

Emmanuel Levinas wrote about shame in On Escape by recounting a scene from Chaplin’s City Lights. The Tramp is trying to blend in with some wealthy socialites at a New Year’s Eve party. He’s tipsy, having been drinking the free champagne, and when someone hands him a small silver whistle for the purposes of celebrating, he pops it into his mouth and swallows it. Now every time he inhales or hiccups, the whistle bleats. At one point the room quiets down, and a man in a cummerbund, standing beside the piano, is poised to begin an aria. But just as he opens his mouth, Chaplin’s whistle sounds shrilly, and everyone turns around to stare. He’s helpless to control it, this noise that is a metaphor for himself, for his body, for the fact that he shouldn’t be there at all. He runs outside and collapses on a bench. But even here, the whistle inadvertently hails a taxicab, then attracts a pack of stray dogs that won’t leave him be. When he returns to the party inside, the mangy dog pack follows him, ruining the party, upsetting all the furniture . . .

Japanning

How shallow it is! I just measured it—nine inches deep, just deep enough to house the books. And I’m asking it to harbor so much significance. I want it to be a “deep image” of our family’s past. But the next moment I see it for exactly what it is—a hollow prop, a piece of handsome kitsch. Why can’t I just let it be what it is—something shallow? A convincing replica, a simulacrum?

Kitsch

I spent my late teens and young adulthood attempting to fashion for myself a life that felt earthy and grounded. I worked on organic vegetable farms in North Carolina and on apple orchards in Vermont. I lived in a cabin in the Green Mountains, twelve miles from the nearest village; squatted for a year in a defunct forge without plumbing; and kept a foam mattress in the back of a station wagon when I drove cross-country. That was the summer that Into the Wild came out, the book about Christopher McCandless—the white kid who threw out his wallet, abandoned his car and his college degree, and walked into the Alaskan wilderness in search of himself forever. He died after a hundred days of foraging for wild edibles. I spent that fall at a dharma center in Greenfield, trying to become more fully alive. Aliveness meant presence; it meant you had no past. The idea was that you could become a portal for anonymous energy rippling through your body like the aurora borealis. But really, I was seeking the same thing my family had sought when they whitened the family name, silently, from Finkelstein to Finch.

Loper

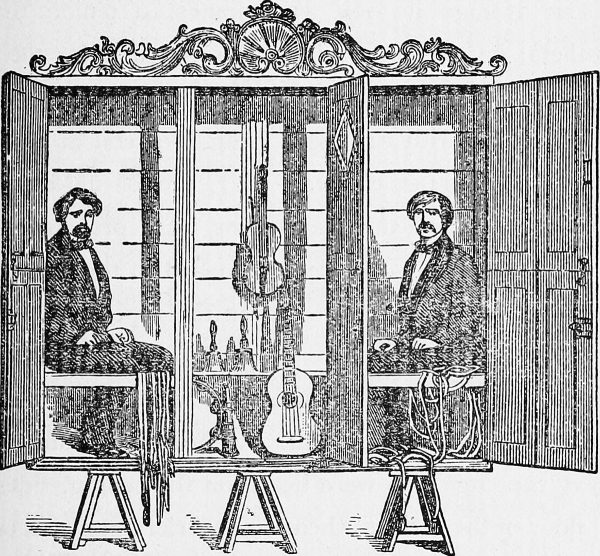

Houdini was a Jew. His father, a rabbi, emigrated from Hungary in the 1880s. I learned this from a book subtitled The Art of Escape by the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips. Houdini’s father failed to sustain himself and his family through his work as a rabbi, so the son became obsessed with succeeding in the new world—on its own performative terms. He ran away from home when he was twelve and changed his name. One of his most successful escape acts was called “The Metamorphosis.” In it, he would ask members of the audience to tie him with rope and put him into a sack. The sack would then be placed into a trunk, the padlock would be shut, and the trunk would be placed into a wooden piece of furniture. The Spirit Cabinet was first used by the Davenport Brothers, a pair of traveling spiritualist-magicians who claimed to be able to communicate with the dead. They would climb inside the cabinet, and when the doors were closed, cacophonous music would begin to play with hands and feet poking through the holes in the structure. “For Houdini, the whole notion of identity,” Phillips writes, “was something one escaped into from the past.”

Muntin

We’re so much better at naming the surfaces of things than at sounding some hidden interior. Flitch, gadroon, japanning, loper, ogee, pilaster, quartersawn, rabbet, splat . . . From researching some old furniture dictionaries, I learned that the secretary is an imitation of the Sheraton style of cabinetry produced in late eighteenth-century England and that its handsome veneer likely comes from mahogany burls—those bulbous shapes a tree grows to protect itself from some trauma or infestation. Tiny knots, formed by aborted buds, are what create those delicate patterns so highly prized by furniture makers, artists, woodworkers, and thieves.

Niche

I am named after my great-grandfather. A gentle giant, my grandmother said, he was beloved by “the Indians” who helped him and his brothers clear the forest where the family hotel was built. The Parkston was located in the town of Livingston Manor, New York, in the Catskills. It burned to the ground sometime in the 1960s. I wrote all this down and last summer drove out to take a look. All the trees were still cut down. In place of the hotel there was a camp for Hasidic girls from Brooklyn called Camp Na’aleh. An elder patriarch came out of the camp office as soon as my car hit the gravel driveway. We spoke for less than a minute in the parking lot. When I mentioned the Parkston and tried to explain my Jewish past, he waved his hand through the air and turned away, and in this gesture of being dismissed, I felt a little twinge of recognition.

Ogee

I remember two facts about my great-grandfather, who died when I was five. One, he walked with a cane that had a rubber stopper on the end. Two, he wore false teeth. He would remove them sometimes—ta-da—like a drawer from the dark soul of his mouth, a performance that scared but delighted me and made me want to sit at his feet and learn more. He must have been a smart investor. I once found, tucked into the secretary, a single sheet of graph paper on which he had tracked the ups and downs of his stocks during the weeks of November and December 1977. The miniature numbers were handwritten inside each cell of the graph paper’s honeycomb. Here is where the honey was hidden: Am. Cyanamid, Am. Home PD, Avon Prod, AT&T, Bank of America, CBS, Colgate-Palm, Eastman Kodak, Exxon, Ford, Gen Elec, Gen Motors, Gillette, Heinz, Hercules, Int Nickel, IBM, Johnson & Jn, La Land + Exp, Lehman, Marathon, Mobil, Morgan JP, Polaroid, Sears Roebuck, So Pacific, Sperry Rand, Xerox. The penciled numbers bobbing on the page looked like debris floating in the wake of a ship: 29 1/2, 29 3/4, 31 3/8, 32, 29 7/8, 30 1/2.

Pilaster

“Experience has fallen in value,” according to Benjamin’s “The Storyteller,” the essay in which he accounts for the decline of storytelling among the European middle classes. Benjamin was the chief secretary of modernity. He kept lots of files. One of the stranger folders in his magnum opus, The Arcades Project, is labeled “The Interior, The Trace” and contains psychoanalytic readings of domestic furniture. The diagonal positioning of chairs in a living room? This implies “the unconscious retention of a posture of struggle and defense.” An armoire? It suggests a military fortress “surrounded in ever-widening rings by walls, ramparts, and moats, forming a gigantic outwork, so the contents of the drawers and shelves . . . are overwhelmed by a mighty outwork.” In one clipping, he imagines the domestic interior as “a spider’s web, in whose toils world events hang loosely suspended like so many insect bodies sucked dry. From this cavern, one does not like to stir.”

Quartersawn

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you this little Japanese ivory carving, a netsuke, suspended on my mantel, another prop I’m not sure how to account for. Should I make it disappear? I could burn it the way the Kenyan government burned 105 tons of ivory a few years ago. But I prefer to assume the “feeling of responsibility toward his property” that Benjamin uses to describe collectors, those “physiognomists of the world of objects.” So let’s see. I spy, in this intricate carving, a miniature river flowing past a tall pagoda. I spy some flowering trees, two figures bent over a book, someone pushing a canoe with a pole, some serrated mountains high above them. And the whole scene is seated in a little stand of ebony. What story is being told by this fugitive whatnot? Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History” contends that even the smallest of cultural treasures is evidence of plunder, spoils being carried off in the procession of the victors, victors of who have just . . . what? Sacked a city? Poached an elephant and sawed off its tusks? Removed gold fillings from the teeth of the laborers before they’re marched to the gas chambers? I don’t mean to be flippant, to suggest my great-grandparents were barbarians or Nazi sympathizers—far cry—but that the things they collected are emblems of the racial, cultural, and economic supremacy they preferred to their identities as Jews and outsiders, refugees.

Rabbet

Something happened in his family when Sigmund Freud was ten years old. His uncle was arrested for selling counterfeit money—one hundred fifty-ruble notes to be precise—and he spent ten years in jail. The story was reported widely by the Viennese press, and it cast a large shadow over the entire family. The family was so ashamed of Uncle Josef’s case—it linked them to the stereotype of the greedy, corrupt Jew— that it became a family secret. Freud scholars Maria Torok and Nicholas Rand say that the whole family “withdrew into a cocoon of silence,” which led Freud to inherit “a trauma of inaccessibility,” stemming “from the prohibition against asking questions, from the impossibility of knowing.” As an adult, he would, of course, devote his life to researching the dynamics of repression. The threat of silence and the shame that silence was meant to conceal—he hoped to dispel this curse through analyzing the creative language we give to dreams. On page 466 of The Interpretation of Dreams, he offers a dream fragment of his own that suggests these difficulties: “I demand information of a grumpy secretary, who, bent over a desk, does not allow my urgency to disturb him; half straightening himself, he gives me a look of angry refusal.”

Splat

When I told a friend about this essay, she seemed skeptical. Rather than imitate the form of the secretary—with all its tidy, watertight compartments—why not try something more fluid, more life-affirming? Why not write, she said, in the form of an octopus?

Tracery

I have placed a copy of the Torah inside the secretary. An adolescent gesture, for sure. It was given to me in Jerusalem by my friend Danny, whom I went to visit when he was studying at yeshiva, the year before he entered rabbinical school. All week we traveled around: camped out on the Golan Heights, listened to the missiles being fired into Syria, got stoned at the headwaters of the Jordan, floated on our backs in the Dead Sea’s stinging saltwater. This was years before I learned about my heritage—otherwise I would have immediately taken to a kibbutz. “I feel like an outsider in a most profound sense,” I wrote in my journal, sitting outside the old city’s limestone walls. “I do not have ‘a people,’” I lamented, “and my sense of community lacks historical structure or substance.” So I learned to move around, to camouflage myself, to squeeze into tight places. In one study, scientists found that because of their restless minds, octopuses in captivity will get extremely bored and stressed out if they’re not stimulated. They found that octopuses who spent time in bare tanks began eating their own arms, a behavior they ceased when placed in tanks with lots of hiding spots and knickknacks.

Upholstery

My grandmother was eaten by an alligator, not an octopus. The way it happened was this: after she died, she donated her body to the hospital. Six months later, we claimed her plastic bag of cremains, tied off with a pink ribbon. We weren’t sure exactly what to do with it, so we brought it to the lowlands of South Carolina, a place that she loved. One afternoon we walked to a wooden footbridge that crossed a quiet lagoon, a beautiful spot. There, we emptied the bag of its pink grit and coral nub and tossed in some dried rose petals after. We watched in silence as this material slowly blossomed and sank into the dark water. No sooner had we done this than an alligator appeared from the edges of the lagoon, where it had been concealed beneath the trees. It floated toward us slowly, ineluctably, and then opened its mouth wide to let the cremains in. It accepted her like no one else had her entire life. The reptile was a ferry, its body a gondola. Everyone gasped from the bridge above, aghast. My grandmother was deathly afraid of the chthonic, of anything earthly. She played bridge five days a week. She volunteered for the symphony every year, making phone calls to raise money. Being eaten by an alligator would have been the final humiliation. But as I see it, the alligator’s presence at our family’s ceremony was a beautiful eventuality. Swimming away, it enacted the ultimate closure—the kind that our family is forced to invent for itself—for we don’t know how to do death, where to put death.

Veneer

During the pogroms of 1882, an Odessa doctor named Leon Pinsker wrote a Zionist pamphlet in which he made a diagnosis. The world is haunted by Jews, he said, who persist like apparitions within countries that will not absorb them. “If the fear of ghosts is something inborn,” he speculates, “why be surprised at the effect produced by this dead but still living nation?” Why be shocked by these violent attempts to exorcize the Jewish phantoms from their midst?

Webbing

I don’t want to be judgmental about my ancestors’ escape from Jewishness. I understand the racism and the anti-Semitism that was rampant in the States and still is. I’ve read Arthur Miller’s novel Focus, for instance. Published in 1945, it revolves around a character named Mr. Finkelstein. Everyone in his Brooklyn neighborhood wants this Finkelstein out. Mr. Finkelstein, who runs the corner store, faces every kind of aggression and daily humiliation—each morning he finds his trash cans upended, his garbage strewn across the sidewalk—until one night he’s brought within an inch of his life by a group of white supremacists. “If [Finkelstein] would just disappear, just go away,” thinks the protagonist of the book, “for God’s sake go away and let everybody be the same! The same, the same, let us all be the same!”

I just wish they hadn’t been so ingrown and ashamed, refusing to admit that their real name was Finkelstein to their grandson—my dad found out when he was visiting his grandparents’ house in Queens one day; he noticed that the mailbox read Finkelstein, and he asked his mother why. “I’ll tell you later,” she whispered.

Some Sundays I would go over to my grandparents’ house, and my grandfather would teach me how to bake bread. In his den we would listen to funny records by Dr. Demento. He showed me scary movies. I loved him dearly. He taught me how to read the stock market page too. I made pretend investments, and we tracked their progress. One of his rules of thumb was that catastrophes are never just catastrophes. They’re investment opportunities. A massive oil spill, for instance, forcing a drop in Exxon’s stock? The perfect moment to sop up cheap shares.

I couldn’t tell if he was joking. He was always joking, like his ventriloquist brother Herbie, with a joke for every occasion. “I’ve got a million of ’em” was his tagline. But the million jokes vanished the day he died. All except for the one. For some reason there is one I still remember: “Hey kid, wanna see your name in lights one day? Then go and change your name to EXIT!”

Xenolith

My sister has a memory of spending the night at our grandparents’ house in the guest room upstairs and awaking the next morning to the song of the grandfather clock playing the Westminster Chimes. She got out of bed and padded to the top of stairs. She remembers very clearly standing there while our grandfather calls out, “Chocolate croissants are ready,” as she walks down the carpeted steps feeling entirely loved.

I am going to do something a little extreme and place this memory in the same dovecote as a recurring dream fragment that Primo Levi describes in The Drowned and the Saved: he is having a peaceful dinner with his family or with friends or with colleagues (the situation varies) when he suddenly knows that this peaceful setting, this delicious food, this familial warmth, is all just a dream, a mirage from which he awakes violently, in the dream, realizing: “I am once again in the camp, and nothing outside the camp was true. . . . I hear the sound of a voice I know well: the sound of one word, not a command, but a brief, submissive word. It is the order at dawn in Auschwitz, a foreign word, a word that is feared and expected: ‘Get up.’”

Yarmulke

My sister is interested in our family’s past too. She’s an herbalist in Oakland now and tells me vivid dreams in which our ancestors return to communicate with her. She recently dreamed that she became a lemon balm plant. She felt herself rooted in the ground beside a dusty road on the outskirts of a village that she understood to be in Ukraine. She watched a procession of soldiers walk past her, not in full army regalia, but soldiers clearly. They were speaking Russian, and they were dragging the women and children right past her. They were taking them somewhere. In the dream, my sister tries to cry out for them, but she is a plant—a witness who cannot speak—and there is nothing she can do. The vision goes dark and is replaced by another image of a different scene. A woman, in her early thirties, with brown hair to her shoulders, is standing in a crowd of people who have been rounded up and now are waiting. This woman turns to my sister, looks her in the eyes, and says: “Even though I’m about to die, I know that years ago, some of our family got out. They escaped. They can’t kill us completely. They live in the United States and they have children . . . ”

Zayin

It’s true, we do. My sister has three, and my boy turns six this summer. He’s at the age when at least a dozen times a day he asks me—over dinner, in the car, on the toilet—to tell him a story. I run through my repertoire of fairy tales and comic yarns, but it’s the myths that he likes most, so maybe he’s nearly ready for me to start this story. “Myths are often about the inescapable, about the painful discovery of powerful constraints,” writes Adam Phillips in Houdini’s Box. They almost always involve some “flight from something that will be returned to” because there are some things we cannot elude. These are the constraints that give us a clearer sense of ourselves and make the world feel solid.

About the Author

Zack Finch’s poems and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in the Georgia Review, New England Review, the Adroit Journal, Poetry, Tin House, and elsewhere. He teaches literature and creative writing at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in the Berkshire Mountains.