About the Feature

Photo by Best Picko

Home

In 1993, the British artist Rachel Whiteread was commissioned to create a sculpture similar to an earlier work, Ghost, which had involved casting an empty North London apartment in concrete and presenting its interior, solidified. The new sculpture would incorporate the same process, this time utilizing an entire house, the only remaining residential structure in the condemned neighborhood of Wennington Green, as its cast. Imagine the difficulty of Whiteread’s undertaking: pumping every room in a large house with liquid concrete in such an order as to avoid the weight of the material splitting the house apart, then peeling back the structure that had once been the house itself to reveal its negative image, a monument to what had formerly been known as the air in the rooms. The resulting work, House, stood for three months on its weedy patch of land in East London, provoking befuddlement and controversy before it, too, was demolished to make way for development that, it was hoped, would revitalize the depressed neighborhood. The sculpture had never been intended as a permanent fixture. Like other works of art of this nature, transience was essential to its design.

Active Adult

Halfway through a three-bedroom single-story with an open floor plan, we realize we’ve lost my dad. Wandering off is something he does now, like a child or a kitten. My mother’s gotten used to it, along with everything else. Numb is how she puts it.

I’m numb all the time, she says now, loud enough so that other people touring the home can hear.

I know, Mom, I say. I’ll go find him.

We’re touring model homes inside an active-adult community near Wentzville, Missouri, forty miles from where I live in St. Louis. My parents have come to visit for the weekend from New Jersey. My daughter, their granddaughter, is at a birthday party, and my wife is at work. Left alone as the family unit we once were (minus my brother, who lives in Charleston), my parents and I fall back on old patterns.

Throughout my childhood, weekend excursions for my family often meant visiting model homes in new subdivisions across New Jersey. It was, for lack of a better word, a hobby, though for my brother and me it was mostly torture. From Ocean to Sussex County, no destination was too far for my parents’ desire to shuffle through one model after another, pointing out the features that were new and different from our own home in the Central New Jersey township of East Brunswick.

Relief

On the way to Wentzville, my father jokes that soon I’ll be eligible to move into an active-adult community myself. He can still make jokes, or at least point out absurdities such as this. He knows how old I am, generally, though specific dates confuse him. My mother tells me that recently he recalled their wedding as taking place in 1924. In that case we’d better notify the Guinness people, she’d said. After she explained that they were married in 1964, they had a laugh about it. You have to find the humor, she says. She’s been attending a weekly support group for spouses of those afflicted with mental decline, or, as she calls them, Dementia Widows (if there are widowers, she hasn’t mentioned them). Finding the humor is something I assume she got from them.

Visit

According to the website SeeYourFolks.com, which has an algorithm that will calculate how many more times a user will see their parents, depending on their ages and how many times per year you see them, my father is already dead. The fact is, he has outlived average life expectancy in the United States, and so no answer is provided. I reconfigure my input, making my dad one year younger, and the site tells me I will see my parents 1.5 more times.

Model

We were, in many ways, a typical American nuclear family. In 1984, the average number of children according to the us census was 1.85. I used to tell my little brother this meant he was only partially a person. Maybe you’re the partial one, he would say. In response, I would draw my hands down over my body like the hostess of a game show to display how complete I was. We lived in a three-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath colonial in a new suburban development called Normandy Woods. Saplings were planted along the easements, tethered with rubber bungees so they grew straight and true. Our house was on a cul-de-sac and had the number 1 as its street address, which felt like something to be proud of. Our parents weren’t divorced, nor did we have any members of our extended family living with us. My brother and I had our own bedrooms. We had two television sets (one of which was an old black-and-white), a microwave oven that talked (one button prompted the oven to intone Insert probe in its female robot voice, which delighted my brother and me to no end), and a living room with stiffly upholstered furniture nobody ever sat on. We had those tiny spoons with serrated edges for sectioning the grapefruits my mother sometimes gave us for breakfast, which were only barely palatable after several teaspoonfuls of sugar had been scattered over them.

The neighborhood was full of families and houses like that. The only different ones were the Orthodox Jews, who started moving to the area when a synagogue opened nearby. They had lots of kids and their lawns were shaggy with crabgrass. They allowed the tar on their driveways to crack into chunks like the Mojave Desert and left their garage doors open all day long. On Saturday mornings, when my father and I would take long bike rides, we sometimes passed the Orthodox walking to shul.

There go the good Jews, my father would say, and then he would gesture at the two of us on our snazzy ten-speeds and say, Here come the bad Jews.

Model

There are some things I can recall enjoying from the model home tours of my youth. After a day of schlepping from one new subdivision to another, we’d usually stop at a Dairy Queen or a Stewart’s. I liked Stewart’s because the hot dogs were the kind that snapped when you bit into them, and I loved the thin skin of ice on the mugs that you could slide off in pieces with a fingernail, the near pain of those first frosty gulps.

Another thing I liked was when a model we were touring had a laundry chute, which our home in East Brunswick did not. My brother and I always traveled with a few Star Wars figures in our pockets, and it was fun to send them down a laundry chute until someone stopped us. I can still remember the lonely rattle of Greedo bouncing off the aluminum ducts on his way into my expectant hands.

The best, though, were the fake appliances—televisions, stereos, even microwaves—made of hollow plastic that were displayed in the model homes and that could be picked up, with much pantomimed straining and grunting, and thrown at one’s sibling, or simply borne aloft on the tip of finger and balanced the way a circus strongman might do.

Relief

I tell my brother I am working on an essay about our father’s dementia and that it is titled Fuggedaboutit!: A New Jersey Son Reckons with His Father’s Alzheimer’s.

Home

The Normandy Woods subdivision, where I grew up, was built on top of what had been a sheep meadow in East Brunswick. In industry terms, it was a greenfield development project, as opposed to a brownfield project, in which construction happens on land that has already been developed. One way of looking at this is that a greenfield space may be assumed to have no memory, nothing to hamper the developer in any way, as opposed to a brownfield project, where a developer might be dealing with existing structures or underlying infrastructures. Maybe it’s called brownfield because when you build there you’re dealing with someone else’s shit. There’s also land referred to as grayfield, which is described as obsolescent, outdated, failing, moribund or underused. Often, grayfield plots of land are found covered in decaying asphalt.

Relief

Before we can leave to tour the active-adult community, I need to find my car keys, which I’ve misplaced somewhere. I go through each room, grumbling curses under my breath. I can’t remember what I was doing when I came in with them the night before, what I might have done with them. Don’t you start, now, my mother says.

Model

The developers of Normandy Woods were Abraham Zuckerman and Murray Pantirer. Both men were Holocaust survivors and Schindler Jews. In each subdivision they built from the fifties on, Zuckerman and Pantirer named a street after Oskar Schindler—such streets can now be found all across New Jersey. In our neighborhood, it was Schindler Court, a cul-de-sac like the one we lived on (ours was named Franklin). A cul-de-sac is a strange sort of street, capped at the end with a bulb—you can begin or end there, but you can’t pass through.

In the late sixties, toward the end of Schindler’s life, Zuckerman and Pantirer brought the man to New Jersey several times. Schindler’s health was failing and he was destitute, having failed at many endeavors since the end of the war, and the two New Jersey real estate moguls tried to do what they could to help. They arranged speaking engagements at congregations across the East Coast. They bought him clothes and shoes.

When he visited, Schindler stayed at Zuckerman’s well-appointed home in the suburbs. The children called him Uncle Oskar and spoke to him in English or Yiddish, but he could only respond in German. Kinder, Kinder, he would say, patting their heads. At dinner parties, Zuckerman always introduced Schindler as the man who saved my life. This was decades before the Spielberg movie, and many of these Jews, born and raised in the usa, had no idea who the tall, smiling German in the room was.

Active Adult

The active-adult community near Wentzville is similar to the one where my parents live in Jackson, New Jersey. Most of these places have at least one man-made pond or lake and a golf course, a security gate with a guard in uniform. They have vaguely pastoral names, tasteful and indistinguishable, somewhat like the names of companies that manufacture organic food products: Winterbrooke. Stone Creek. Lake Ridge. Heather Gardens. Each home here in the Wentzville community features a swell in the yard just underneath the picture window, as if each residence is buoyed along on its own personal wavelet.

Relief

In Central New Jersey there’s an East Brunswick, a North and a South Brunswick, and a New Brunswick, but there is no West Brunswick. My friends and I used to imagine a West Brunswick, though, and would even set D&D campaigns there. We referred to West Brunswick as The Land New Jersey Forgot.

Visit

All the way to Wentzville, my father fusses with the temperature-control knobs and air vents on the dashboard in front of the passenger seat, trying to find a temperature that satisfies him. He is agitated, constantly mumbling to himself. He exists in a bubble, a prison of the present, where any bit of discomfort is an eternity because he can’t imagine a future where the condition changes. If he is walking in the rain, he will always be walking in the rain. If the radio is too loud, it will grate on his ears forevermore. For most, the present is like the car I’m driving, simply a vehicle bearing us from the past to the future. But my father doesn’t know where he’s coming from or where he’s going.

Goddamn, he murmurs, slapping the vent closed entirely, then opening it again.

What? I ask.

Nothing, he says.

In the back seat, my mother tells a story about traveling from New Jersey to visit my father at Miami University in Ohio when she was eighteen, the first time she’d ever flown. These days, she brings up their past more than she ever did, desperate to preserve what slips from my father’s mind.

I wore a yellow suit, she says, with a pillbox hat that matched. It was the kind of thing a young woman wore when flying back in those days. When we landed I spotted your dad through the little window, waiting for me on the tarmac, and I thought about what I would look like to him coming down from the plane in my yellow suit, whether I would live up to his image of me after all those months apart.

My father pauses in his fussing to listen, a wistful expression on his face.

I remember it well, he says, but we don’t believe him.

Model

During the summer between my high school graduation and my first semester of college, I worked for my father’s friend Ivan. Ivan owned a company that cleaned up construction sites in the new subdivisions and condo complexes that were springing up everywhere in Central New Jersey in the eighties. His crew was made up mostly of Black and Mexican guys from New Brunswick, but that summer his stepson Stewie and I had been conscripted into service. You’ll need money for books, my father told me. And any fun you plan on having. My dad was also working that summer for Ivan, as a foreman. It was funny to see the two of them together surveying the work sites—my bespectacled father in cutoff jeans and tennis shirts, the professor in summer, next to Ivan, pure Brooklyn in his black leather jacket, polyester trousers, and a shirt unbuttoned to show the gold Chai pendant caught in the coarse hair on his chest. Stewie and I usually worked inside the models, taking advantage of the air-conditioning. We laid sheets of plastic over the new carpets, listlessly sprayed and wiped the surfaces in the kitchens and bathrooms. We shot blue liquid into the toilets so they always looked clean for prospective buyers. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew sweated out in the sun. Stewie always brought a boom box. We’d crank “Burning Down the House” and sing along. Sometimes we’d go inside a closet and close the door to smoke cigarettes or nap in the cool dark, curled on the soft carpet like puppies. Once Ivan caught us like that and screamed bloody murder, but Stewie laughed it off.

The one nasty job we couldn’t get out of was dredging the manmade ponds that would eventually be the centerpieces of the subdivisions but that now were convenient dumps for anything the construction crews wanted out of their way. They’d hurl cardboard appliance cases into the water, boxes full of nails, clumps of concrete and broken cinder blocks, splintered beams that went all mossy, not to mention the hundreds of Styrofoam cups and containers, pizza boxes, banana peels, and the myriad of unmentionables they went through in the course of a day. The regular guys on Ivan’s crew wouldn’t venture into the ponds, claiming they couldn’t swim, but mostly everyone just wanted to get even with us for slacking most of the day and getting an equal paycheck at the end of the week. Stewie and I would strip off our shirts and sneakers and pick our way barefoot down banks of jagged riprap. Usually, the aeration fountains hadn’t been installed yet and the lake surface would be filmed with green algae. The water had the consistency and temperature of fresh saliva, and the primordial silt at the bottom sucked our legs almost up to the knees. We hip waded through billowing chains of slimy frog eggs, each with the tiny black seed of a tadpole eye at its center. Whatever we encountered with our stumbling knees or searching fingers we would drag out. Once we had to pull out a half-sunken and cracked Johnny on the Spot, which took an hour. Ivan and my father would watch from the banks along with the rest of Ivan’s crew, hooting and laughing as we grimaced and tried to keep our noses and mouths as far from the scummy water as we could.

My father was the one who started singing the Jaws theme—da dum, da dum, da dum—and the others thought it was a riot. Soon they were all doing it while my dad waved his arms like a conductor.

Home

A friend of mine brings a souvenir for my daughter back from Haiti, a six-inch-tall model of a brightly painted Caribbean-style house made entirely out of corrugated cardboard. The house is green and yellow, with a rust-colored roof. Its features include a dormer window and a lovely front porch, complete with detailed railings. The green front doors are positioned slightly open, revealing a screened door with slats through which, were it a real house, the island breeze might pass. It’s a clever little thing, an astonishing display of craftsmanship, which its maker likely carries out several dozen times a day in order to meet the demands of the tourism trade. We place it high on a shelf in my daughter’s room, which is why I’m surprised to find it on the floor a few days later, torn into pieces. My daughter would have had to place several of her thicker books on top of a chair to reach it. I wanted to see who lived in it, she tells me later.

Model

White, unpainted architectural 1:100 scale-model figures come in packs of one hundred, assorted. From Amazon: This pack of 100 people offers a mix of varying genders and positions and is suitable for any scale modeller. It is worth mentioning that no children are included in the pack. Also from Amazon, confusingly: Item’s color might be different from the picture because of the aberration. Each figure stands three-eighths of an inch. The figures, which are created from cheap molds, are devoid of detail, faceless, with mitts for hands and heavy, ambiguous footwear. Their clothes appear as candle wax poured over them. The most clearly defined of the figures is a man in a suit and hat, the cartoonish thickness of his sport coat bringing Joseph Beuys’s “Felt Suit” of 1970 to mind. One figure of a woman appears to be wearing an apron, beckoning hello or goodbye with a globby appendage.

Visit

It’s maybe a year and a half before the excursion to Wentzville when I first notice something’s wrong. I’m visiting my parents in Jackson, heading back to their house after running errands with my father. We’d gone to pick up some things for dinner, and also to replace the battery on my wristwatch at a strip mall where I’ve replaced the same battery once before. For some reason, I like this particular jeweler, though changing a watch battery is no big thing—you can get it done anywhere. Maybe it’s just the kind of errand I like running with my father, something I would have done with him back when I lived at home, along with getting new tires or having mower blades sharpened or paint mixed at the hardware store. Sometimes when I do these sorts of things on my own, even as a forty-eight-year-old, I feel like an imposter, someone pretending to be the sort of man who knows what tires to put on his car or whether to use gloss or semigloss, things I always relied on my father to advise me about. In any case, I’ve lived with a dead watch for months, waiting for this trip to New Jersey, and now it’s finally fixed. I’m admiring it, ticking like a champ on my wrist, when my father stops at an intersection about a mile from his subdivision and just stares forward as if no further action is demanded, as if we’ve arrived. It’s a busy intersection with four corners of retail, two banks, a gigantic new Walgreens. Cars behind us begin to honk and soon it’s a Jersey cacophony. But my father continues to gaze into the middle distance, mouth slightly open, his fingers tapping out the rhythm on the steering wheel of a song playing on the radio, “Lyin’ Eyes,” by the Eagles, a song he’s always loved.

Dad, I say. Earth to Dad.

Model

Props for staging model homes can be purchased from PropsAmerica.com. From the “How to Choose TVs for Staging” section of the website: Asides [sic] from using a prop TV to fill empty wall space, it can also be seen as a work of art and an important part of the home that families gather around to spend quality time together. Advice is available on the proper placement and angle of prop TVs relative to size. Again, from the site: Granted no one will be watching your TV but the more realistically it is placed the more believable it will be. The “Fake Foods” section of PropsAmerica.com displays an array of items from slices of lime to full main courses, like some plastic lamb chops, colored medium rare and fanned artfully next to some stalks of asparagus and new potatoes on a white plate. My personal favorite is the set of 6 Saltine Crackers for $14.95, evidence that the folks at PropsAmerica have taken into account the humble and mundane. In the photograph, the saltines appear to be made of orange rubber, resembling a hybrid of crackers and the cheese that might top them. Also available are a myriad of options when it comes to bread and rolls, from an Artificial French Loaf described as “soft to the touch” to a set of 2 Artificial Bagels with Cream Cheese or 3 Whole Fake Bagels without.

Relief

Six or so months before my parents’ visit, I’m on the phone with my mom, trying to make sure she’s finding time for “self-care.” The jargony phrase stumbles from my lips, and I know my mom doesn’t like it. As a family, we’ve always prided ourselves on not being taken in by feel-good, New Agey stuff. We’re unsentimental to a fault, though we’ve started saying I love you at the end of every phone call, a new practice these last six months.

You’ve got to find time to just breathe, I say, a little giggle escaping with the words.

She tells me the neurologist who’s been seeing my dad advised her that when things become unbearable, she should go into the bathroom, close the door, and scream into a pillow.

Have you been doing that? I ask.

Once or twice I have, she tells me. I really have.

I’m walking next to a tall chain-link fence, around the part of the campus where a tremendous hole has been dug for the new underground parking garage. It’s a blustery day, and in front of me three architecture majors are trying to keep the foam-core models they’re carrying from sailing off like kites. I tell my mom about the sophomore who recently jumped off the edge of the hole and dropped fifty feet to his death.

Oh, be careful, she says.

I keep telling everyone how she said that—be careful—as if suicide is something that might happen to me by accident. Nobody seems to think what she said is as funny as I think it is.

Home

The American artist Mike Kelley spent the months before his suicide in 2012 fabricating a full-scale model of the suburban house where he grew up. From the outside, “Mobile Homestead” is indistinguishable from other one-story ranches of its kind, the kind of house a child could easily draw, a few low rectangles and triangles. The work of art is meant to live up to its name; it can be hitched to a semitruck and transported easily from place to place. But when “docked” at its home on a lot across from the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, a port in the floor of the house opens to a warren of underground rooms, work and exhibition spaces meant to serve contemporary artists and community groups alike. In an interview, one of his last, Kelley stated that the basement would be “reserved for secret rites of an antisocial nature.”

You descend a ladder to one floor and then there are more ladders and you keep going down.

Model

In fifth grade, the woman I took private art lessons from invited me to take part in her Saturday class, the one where students drew from a live nude model. She even spoke to my parents to convince them there was nothing vulgar about drawing the figure from life, that for an artist it was the same thing as drawing a vase or a hat.

My art teacher lived out in the sticks on an overgrown parcel of land with a crumbling barn and a bunch of animals, including a bison her husband had raised and a raggedy peacock who rushed to our car when we stopped at the end of the gravel drive in order to pick bugs from the grille.

There was a sort of reverent hush in the studio as the model entered and sat on the edge of her platform, and the scrapes and squeals of students adjusting their easels and getting their stools in place sounded louder than it had before. An older woman gave me a tight smile, and it occurred to me that she didn’t think I belonged there, but when my teacher breezed in, her wild, curly hair flying in all directions, she introduced me to the room as her favorite student and I flushed with pleasure.

The model shrugged out of her terry robe and draped it over the back of a folding chair. We began.

Later, when my father picked me up, we pulled over halfway down the long driveway leading out of my teacher’s place, as we always did, to look at the bison in his grassy enclosure. The giant creature stood immobile, muzzle low to the ground.

Well? my father asked.

It was okay, I told him. Ms. Sutton made us do a lot of contour drawing.

I’d never been crazy about contour drawing, because you couldn’t linger over the details, which is what I loved to do.

But my father wasn’t asking about the lesson. He wanted to know about the naked lady.

Relief

Nothing. When I ask him to help me with material for this essay, my brother has nothing to say. He doesn’t remember the model home tours, the Star Wars figures down the laundry chutes, the fake TVs, any of it. He’s five years younger than I am, and so he would have been just a tiny kid. But still, you’d think he’d remember some of it.

Home

A few years after the Orthodox started moving into Normandy Woods, someone spray-painted the word JEW in tall, shaky, red letters on the garage door of a house on Schindler Court. The morning after, with the neighborhood abuzz, my father walked us down the street and we stood there, along with others gathered in small groups, and watched the police take a statement from the family whose house had been vandalized. The spinning light at the top of the police car made no impression whatsoever on the bright morning. The funny thing was, the family was not one of the new Orthodox families. I seem to remember they may not have been Jews at all.

My father said to my brother and me, You see, it can happen anywhere.

We knew what he meant when he said “it.”

It was probably just some stupid kids, I said.

The world order I understood was composed of good and bad kids, bullies and the bullied.

Doesn’t matter, my father said. Again, we understood what he meant, or thought we did.

Murray Pantirer described his existence after the war as a “double life.” There was his life on the surface in America: the suburbs with their long, green summers and hissing sprinklers, the chimes of the ice-cream truck as the sun began to dip, the happy shouts of his own children in their sturdy, bright clothes. But there was another life underneath that, all he’d experienced during the war, which he endeavored mightily to keep buried. There were no photographs or souvenirs from this life to be displayed in the curio cabinet, as there were for the happy life he’d made in Livingston, New Jersey. But the other world was always present. It filled every room of every home he ever built.

Model

Riprap is human-placed material piled along shorelines to aid in wave absorption and prevent erosion. It is used for slope protection on bridge abutments and to protect levees. Riprap, which can also be called shot rock, rock armor, or simply rubble, is most often composed of granite, but may also be made of modular concrete blocks. An online riprap calculator tells me that a ten-by-ten, nine-inch-deep plot would require 4.17 tons of riprap to fill, which honestly seems like a lot. Sometimes pieces of demolished concrete buildings are used as riprap, granting these destroyed structures a second life as protectors against the violence of time and nature.

Active Adult

It occurs to me now that what my parents most admired was the pristine state of the model homes we visited. No dust bunnies raced along the molding when you walked down the hall, no cobwebs waved from the corners up above. Carpets were spotless and redolent of bright static electricity. The stoves sparkled, the ovens had never known a spitting roast, the sofas and easy chairs placed just so in the living rooms did not sag. Nobody had argued in these houses, or come down with the flu, or entered through the front door despondent after losing a job or through the laundry room with a lousy report card tucked inside a backpack.

My parents struggled daily to establish such an immaculate state in the house we actually lived in. They vacuumed and dusted obsessively. Clutter was not allowed anywhere. After each and every dinner, my mother wiped down the kitchen and degreased the oven. She loaded the dishwasher and turned the knob, after which, every evening, she would declare, The kitchen is closed. Our living room was like a diorama in a museum. The only thing missing was the glass wall to separate the space of actual life from the scale models of a family who looked like we did posed as we may have lived.

Model

Two songs I’ve got on repeat: The first is Dionne Warwick’s rendition of the Burt Bacharach/Hal David ballad “A House Is Not a Home,” from 1964. The song achieved moderate chart success. It’s likely my parents heard it on the radio that year. Warwick, wringing heartbreak from every last ventricle, sings about how a chair can be a chair even without someone seated in it, but how a house can’t be a home without someone there to hold her tight. I think about just what she means. A structure may resemble a house—imagine the simplest version: a peaked roof, a chimney, windows, and a front door with a welcome mat, something a child might draw—but, even standing among others of its kind, if it’s empty, it’s only a sign. House. Apply that to chairs, and the song presents a bit of complication. What Bacharach and David mean, I think, is that a chair is a functional object. It isn’t devoid of purpose and meaning if it isn’t being used. Otherwise there would be a different word for a chair with someone in it. But a home’s use goes well beyond the merely functional, and so can only be a home if it contains the complex web of relationships it’s meant to house. Unused, empty, or containing only one lonely soul, it’s just a house.

The other song I keep listening to is “Home,” by new wave queen Lene Lovich, another song that explores the semiotics of home. “Home is where the heart is,” goes the clichéd expression, and Lovich starts from here, as many of us might, summoning the fantasy of a happy, loving place. She keeps going, though, revealing the word’s more complex, darker associations: the suspicions, accusations, and controlling impulses all living under the same roof. After grinding lyrically through all the aggravation and fuss conjured by the word, Lovich pleads with the object of her desire, a person who, we suddenly realize, has been sitting here this whole time listening to her screed, to whom, she sings, “Let’s go to your place.”

Home

My brother calls. He still doesn’t recall the model home excursions from when we were kids, but he asks if I remember that time Dad brought us to watch a house being built in one day. I do, dimly, though it wasn’t a house—it was a Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall. These are often prefabricated, erected by members of the church in what is called a “quick build.” I watch a few time-lapse videos of “quick builds” on YouTube: shadows of clouds rippling across the ribs of a slatted roof, shingles cascading as if vomited, people and trucks and forklifts whizzing in and out, then the darkness of night. I remember we had a box of glazed from Mickey’s Donut Land with us in the front seat of the car. I remember my dad pointing out the fact that there weren’t any windows in the structure. Easier to build that way, he said. But boy is it ugly.

Relief

In their home, my parents have a lot of fake food, or, more accurately, utilitarian and decorative items that are food-shaped. They have those miniature, plastic corn-on-the-cobs with prongs, meant to serve as handles for eating actual corn-on-the-cob. They have a ceramic baked potato meant for keeping actual baked potatoes warm, complete with a pat of butter on top that serves as a handle (which never made much sense to me, since you put the butter inside the potato once you’ve sliced it open). On their kitchen pass-through stands a three-tiered dessert display filled with tempting muffins and cakes and pastries, all of which are actually candles.

Once, inspired by an article in one of my mother’s home-decorating magazines, my father shellacked several loaves of fancy bread: a round loaf of black bread, a long baguette, and an oblong seeded rye. These were placed in a ceramic basket (itself fashioned to resemble a wicker basket) in the center of the dining room table, where they sat proudly for several years until my mother noticed a line of tiny bugs trailing across the table and spiraling down one of its legs. My father discovered the source of the infestation to be the loaf of petrified rye. He brought it out to the driveway and chopped it in half with a hatchet (the same hatchet he’d use, a few years later, to split my skateboard in two as punishment for a C in algebra, a D in chemistry, and an F in photography). Inside the rye, the tiny bugs had excavated a home, complete with a chamber for their young, tiny white grubs that waved wildly at the awful light of day.

Model

My mother calls to say they’ve been back to the neurologist and that, when asked, my father will claim the year is 1952. Tasked with sketching the face of a clock with all its numbers in place, my father draws a lopsided circle, which he stares at for several minutes before laying down the pencil and going into what my mother will describe, like she’s talking about a toddler, as a “total meltdown.”

Home

In 1974, the Icelandic artist Hreinn Fridfinnsson built a small house in a remote part of his country, erected to the specifications laid out by a character, Solon Gudmundsson, from the 1938 novel Icelandic Aristocracy. In the novel, Solon, an elderly eccentric living in a fishing village, wants to build a house inside out, based on the notion that if wallpaper is supposed to please people, it should be on the exterior so that passersby might enjoy it. Fridfinnsson’s house resembles a house a child might draw: a rectangle with a triangle on top. It is papered on the outside in white striped with pale blue. Curtains hang on the outside, exposed to the weather. In the picture I’ve seen, the house is tiny inside a harrowing landscape of craggy rock and pale northern sky. From Art Now: Scandinavia Today: “The existence of this house means that ‘outside’ has shrunk to the size of a closed space formed by the walls and the roof of the house. The rest has become ‘inside.’ This house harbors the whole world except itself.”

Everyone on the planet has been living inside Fridfinnsson’s house since the 1970s, which raises the question of what might happen if another inside-out house were to be constructed. Which would contain which?

Visit

I find my father in the basement of the model we’ve been touring, sitting alone on a bench made of two-by-eights perched on cinder blocks. Oddly, someone has constructed a small chapel down here, complete with several rows of cinder block pews and a cross as tall as a person, just two pieces of lumber roughly nailed and held up by three more cinder blocks arranged in a tripod formation. I take a seat next to my dad on the bench. He looks at me, says, Hey, Bud.

Buttresses of yellow light slant in from the basement windows, making dust sparkle in the air. There is the smell of water and earth, of excavation.

My father asks, What is this?

It’s the Midwest, I tell him.

What I mean is that prayer is common here in a way it isn’t in New Jersey. I’ve seen prayer spring up in parks, at the movie theater before the lights go down, at study tables in the public library. At Panera Bread, a group of young people will suddenly join hands and bow their heads over their sandwiches and bowls of broccoli-cheddar soup. Here, I can only imagine that someone on the construction crew is a pastor who’s found a way for some of his coworkers to make time for Jesus during the workday, or maybe some of the salespeople dip down for a quick prayer before the prospective buyers begin to show up on a Sunday. Oh heavenly father, grant me on this day my commission . . .

It’s kind of pretty in its way, my dad says.

He sounds like himself, for a change, the man who taught me to appreciate the flickering strangeness that sometimes rises out of the mundane.

Rustic, he continues, like a church in a peasant village in some little chalet in France from the 1600s.

In his professional life, my father was a professor of history.

We sit for a while on the bench, our elbows touching, having assumed for the moment the attitude of worshippers.

Home

One Franklin Court was brown. The palette of the entire neighborhood was earthy, with the exception of a few houses painted a dusky blue, and one greenish one my parents called the Vomitorium. When I visit New Jersey, I always make a point of driving back to the old neighborhood, though my parents live an hour south of East Brunswick these days. I don’t know why I make these pilgrimages—my childhood isn’t something I yearn for. I guess it’s like going back to a passage in a book to make sure I’m remembering it right.

The house has been repainted. It’s a sort of khaki color now. The color startled me the first time I saw it, like seeing someone I knew well wearing a strikingly different hairstyle. The owners, whoever they are, have affixed a ceramic mask to one of the tree trunks in the front yard, a tawny, wizened thing meant to turn the old oak into something out of Lord of the Rings. I would have loved such a thing when I was a kid.

When I visit, I sit inside my car, idling at the curb. I feel a strange sense of authority. I almost want someone to confront me as a stranger; it’s the suburbs after all, and you’re not supposed to just sit with your car running in front of someone’s property. I was raised in this house, I could tell them, and what could they say to that?

Model

There’s a photo of Schindler in one of Zuckerman and Pantirer’s subdivisions below a street sign bearing his name. Black and white, with the particular chiaroscuro of a late winter’s day, the photo shows the man in a double-breasted suit, holding a cigarette in the effete manner of a European. Schindler is a big man, as wide across as the city mailbox squatting behind him. The trees behind him are bare and the houses in the background are neat-edged and clean. The newness of it all must have astounded him—the rows of simple, identical houses encased in vinyl siding; chain-link fences and modest islands of manicured shrubbery; kidney pools covered tight for winter—traveling as he was from a continent where the scars of history were fresh to arrive in a place designed to have no memory.

Visit

On the ride to Lambert Airport, my dad sits in front with me, fussing with the knobs on the radio and the air-conditioner, muttering softly to himself. When we pass a billboard advertising one of the local universities, my father turns to me and says, I used to teach at a college.

He knows that, Honey, my mom says.

I catch my mother’s eyes in the rearview mirror, but only for a second. Her makeup is perfect. She still likes to look pretty when she flies.

When we arrive, I pull their bags out of the back and kiss them both. I watch them through the glinting glass of the terminal, my mom with her hand at my father’s elbow, as if she’s leading a blind man, until someone who wants my spot taps their horn.

House

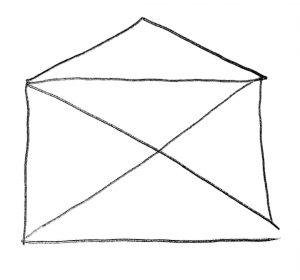

Sometimes when I’m bored in faculty meetings or stuck on a passage in whatever it is I’m trying to write, I draw this house over and over:

The house is a puzzle. My dad showed it to me when I was a kid. The object is to draw the house using one uninterrupted line.

Try it yourself.

It took a long time before I could get it right on the first try.

About the Author

David Schuman’s fiction and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Fence, Catapult, Conjunctions, American Short Fiction, Missouri Review, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and other journals and anthologies. He lives in St. Louis, where he teaches and directs the writing program at Washington University.