By Colorado Review Editorial Assistant Aliceanna Stopher

I’ve been thinking about place, where I come from, and how place informs what I write. Recently I’ve noticed some puzzling changes in myself, in my go-to phrases, my tastes, the settings of stories I want to read or write. When I called my sister to tell her I’ve been making grits every morning and carrying Tabasco in my canvas bag, she teased me before admitting our mother has also lately been praising her Southern cooking. We laughed at each other, our reluctant-northern-Virginia-Southernness, laughed at our mother, the Yankee outsider. I admitted, then, like a secret or a dare, “I’ve found myself writing preach, mama in the margins of the books I’m reading,” which has been the biggest puzzle to emerge out of many otherwise subtle changes.

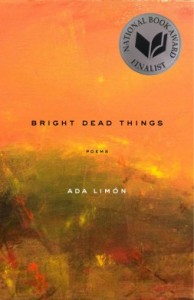

When I stood in line to have my book signed last Thursday by poet Ada Limón, I held my copy of Bright Dead Things close against my stomach. This book is one I’ve littered with preach, mama in my messy ink; hovering next to lines like “I want to try and be terrific. Even for an hour,” and all down the spine of the spine-tingling poem “How to Triumph Like a Girl.” When she signed my copy I stood, grinning blankly, nervous she might accidentally flip a few pages over and find the evidence of my fangirling.

Last Thursday afternoon before the reading, some CSU students were lucky enough to enjoy an informal conversation with Limón herself over a brown-bag lunch. She fielded questions and spoke to process and hoarding weird facts and giving credit to the human animal graciously, with all eyes on her as she made a solid effort to finish her salad. She was bright and funny and I took frantic, messy notes.

Of many glittering gems this is what resonated most with me: Limón spoke to the real-world implications of our art, to accountability in publishing. She said, “What you need to write is not always what you need to publish.” Instead, sometimes what you write serves as a written memory that, once written, can be let go to make space for other things. She talked about survival, about needing to express what’s true and real and alive, but that this kind of writing is not always what the rest of the world needs to read. Considering how personal and raw Bright Dead Things reads, I was blown away by what strikes me now as obvious—the idea that we, as writers, don’t have to give everything to our readers. Some conversations aren’t public. Some writing, whether deeply personal and revelatory or not, is just for the writer themselves.

This semester I’m taking Harrison Candelaria Fletcher’s nonfiction workshop, and I’ve felt this push and pull between what I need to say and what needs to be heard, but I hadn’t yet named it. Limón named this tension so succinctly, and this naming helped me give permission to myself to write what feels urgent to my survival without putting pressure on myself to share it with workshop or to seek publishing it.

Which brings me back to place, to the South. I may never get to the bottom of why my tastes changed from oatmeal to grits when I moved to Colorado. I may never figure out why, seemingly all of a sudden, I’m quick to say “y’all” instead of “you guys.” I may never share what I’ve written about how I can’t remember my father’s Louisianan accent, or what it was like to grow up running with my family’s chickens on the backside of the Blue Ridge Mountains. But in hearing Ada Limón read and in listening to her talk about accountability and survival, I felt deeply grateful to her as a human being and writer. Again and again I found myself thinking, preach, mama, preach.