by CL Young, Colorado Review Editorial Assistant

Around the middle of last year, the age restriction on the Yale Younger Poets Prize was lifted, opening the competition (previously available only to poets under the age of 40) to emerging poets of any age. The Yale Prize has been around for nearly one-hundred years and has launched the careers of more than a few greats—Muriel Rukeyser, Adrienne Rich, and W.S. Merwin, to name a few. When I heard about this change, I was disappointed. Not only because I identify as a younger poet and therefore project my own fantasies onto an opportunity like this one, but because it struck me as a choice to move away from change instead of toward it.

A few weeks ago, an article called “These 9 Young Poets Are Actually Making the Genre Cool Again,” profiling a handful of poets, around or under the age of 30, appeared in Teen Vogue (yes, poets; yes, Teen Vogue). One of the poets included in the article is 27-year-old Ocean Vuong, whose work I first encountered in the New Yorker (yes, 27; yes, the New Yorker) about a year ago. The poem was called “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong,” and I loved it immediately. It sweats as much sincerity as it does violence, presenting the reader with an infinite cycle of damage and repair. Parts of it continue to enter my head unprompted. For me, it is a perfect poem.

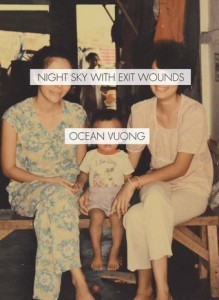

Since then, I have been following Vuong’s work, and when I learned that Copper Canyon Press would be publishing his debut collection, Night Sky With Exit Wounds, I felt strange. I was thrilled that I would get to read a whole book of this poet, yes, but it was more than that. It was a feeling of fullness—of expansion—that such a well-established, respected press had decided to bring into the world a first book written by someone so young. Surely there is plenty of evidence of Vuong’s talent and potential (that poem in the New Yorker alone is enough), but to see one of the major poetry presses in this country publishing someone born four months after me—it is something like hope. Not just hope for what might become of us other young poets, but hope for the future of poetry and what that could mean for the world.

Since then, I have been following Vuong’s work, and when I learned that Copper Canyon Press would be publishing his debut collection, Night Sky With Exit Wounds, I felt strange. I was thrilled that I would get to read a whole book of this poet, yes, but it was more than that. It was a feeling of fullness—of expansion—that such a well-established, respected press had decided to bring into the world a first book written by someone so young. Surely there is plenty of evidence of Vuong’s talent and potential (that poem in the New Yorker alone is enough), but to see one of the major poetry presses in this country publishing someone born four months after me—it is something like hope. Not just hope for what might become of us other young poets, but hope for the future of poetry and what that could mean for the world.

It is essential to engage with work by authors at all stages of life and a great first book can surely emerge from any of these. However, it is my estimation that in order to best continue in this world—this place that is broken and continuing to break—in order to be better in it, one approach might be to listen more closely to the young, to those who are the most direct product of this moment. O that they might help move it toward repair.