by Alex Morrison, Colorado Review editorial assistant

Last month, I was hosting a friend from Baltimore while he used Fort Collins as a launching point to explore Rocky Mountain National Park. I was giving my friend a quick tour of my apartment when he stopped to inspect my bookshelf, a narrow and flimsy piece of furniture with five shelves. I tried to usher him along (“Look—here’s my washer and dryer!”) given that at this late point in the semester, my bookshelf wasn’t the proud, alphabetized display it once was. It was strewn with scrap paper and school supplies, bent staples, and scribbled Post-it notes. Worse yet, after accumulating a dozen Norton guides and textbooks over the course of the academic year, all semblance of serialization and order was gone. My shelves sagged beneath books squeezed haphazardly in between other books, their titles half-revealed. I felt weird as my friend thumbed his way through my volumes, from baseball encyclopedias to an embarrassing collection of Middle-Earth cartography. My personal life as a reader was suddenly exposed in a way I didn’t like. Then my friend turned to me and asked me something that gave me pause:

If there was a fire in your apartment and you could only save one book, what book would it be?

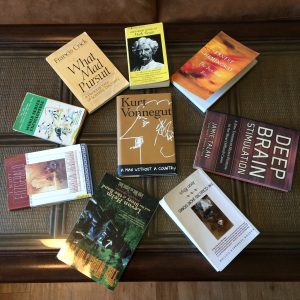

It’s a hokey question, and I still don’t have an answer. My favorite novel, given my genuine love for all things wine and northern Spain, is The Sun Also Rises, but my particular Penguin Classics copy isn’t anything special. Then there is The Collected Short Stories by Jean Rhys, my favorite author, and a difficult volume to track down given that most of Rhys’s short fiction is out of print. That would be a hard one to see burn. There’s Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, the first book I fell in love with (I had all the stuffed animals), but this version isn’t that version, which is likely chewed up and juiced-stained somewhere in my parents’ home in New York. And what about my old neuroscience books? Francis Crick’s What Mad Pursuit, the biologist’s personal account of his co-discovery of DNA, or Jamie Talan’s Deep Brain Stimulation, which was more or less my how-to guide for hippocampal studies during my two years in the lab. Am I ready to say goodbye to these books, to this part of my life? Or my mom’s college copies of French and Russian literature that she let fall to me, some of which, such as The Complete Short Stories of Guy de Maupassant, still need to be returned to the Goucher College library. That book in particular has led a long and varied life, from Baltimore to New York to Fort Collins—shouldn’t I save it?

It’s a hokey question, and I still don’t have an answer. My favorite novel, given my genuine love for all things wine and northern Spain, is The Sun Also Rises, but my particular Penguin Classics copy isn’t anything special. Then there is The Collected Short Stories by Jean Rhys, my favorite author, and a difficult volume to track down given that most of Rhys’s short fiction is out of print. That would be a hard one to see burn. There’s Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, the first book I fell in love with (I had all the stuffed animals), but this version isn’t that version, which is likely chewed up and juiced-stained somewhere in my parents’ home in New York. And what about my old neuroscience books? Francis Crick’s What Mad Pursuit, the biologist’s personal account of his co-discovery of DNA, or Jamie Talan’s Deep Brain Stimulation, which was more or less my how-to guide for hippocampal studies during my two years in the lab. Am I ready to say goodbye to these books, to this part of my life? Or my mom’s college copies of French and Russian literature that she let fall to me, some of which, such as The Complete Short Stories of Guy de Maupassant, still need to be returned to the Goucher College library. That book in particular has led a long and varied life, from Baltimore to New York to Fort Collins—shouldn’t I save it?

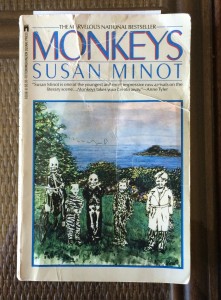

As I consider that one, salvageable work I realize: I’m more concerned with the story of the book than I am with the story within the book. Where has the book been? How did I come by it? Who have I shared it with? Is it in good condition, or is it worn and bent from use? The book that I save needs to have a history, and when I think of these questions, I realize there is only one answer: Susan Minot’s Monkeys.

Although Monkeys is not my favorite book, it is one of them. It is Minot’s first published novel (1986), and it describes, through linked stories, the events surrounding various members of a large New England family from 1966 to 1979. I was given the book during a workshop at the house of one of my undergraduate professors, Richard Macksey, after I told him how I was attempting to write my own linked-novel about a large family.

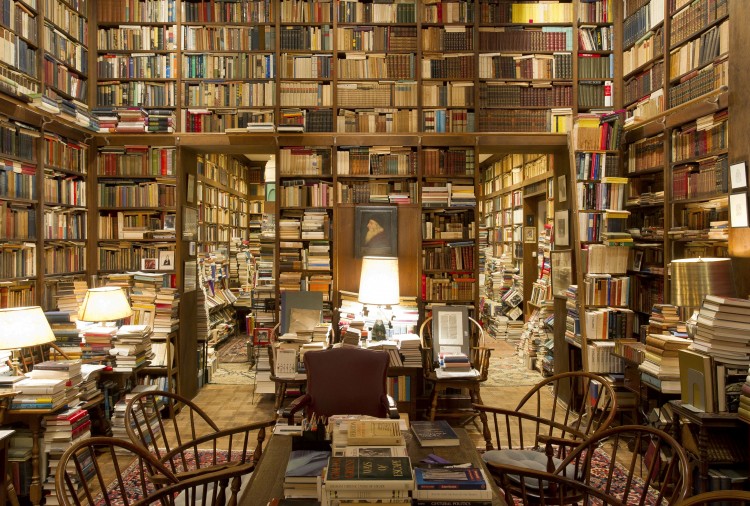

The fact that the book comes from Richard Macksey is fitting, as there is no person I know who loves books more. He presides over one of the largest private libraries in Maryland, comprising over 70,000 books and manuscripts. Attending a fiction workshop at his home in Baltimore was a bibliophile’s paradise, with books quite literally everywhere. I’m pretty sure he lent me Monkeys with the intention of getting it back (Sorry, Professor!), but I know he’d be happy to hear about the journey the book has taken.

The fact that the book comes from Richard Macksey is fitting, as there is no person I know who loves books more. He presides over one of the largest private libraries in Maryland, comprising over 70,000 books and manuscripts. Attending a fiction workshop at his home in Baltimore was a bibliophile’s paradise, with books quite literally everywhere. I’m pretty sure he lent me Monkeys with the intention of getting it back (Sorry, Professor!), but I know he’d be happy to hear about the journey the book has taken.

Because of how much I enjoyed it, I shipped Monkeys to friends in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and California. I’ve gotten the novel back each time, and always with a few more cracks and creases. When I received the book in 2010, it was already well worn; at this point, there is a section of the book’s middle that needs to be held together by paper clip. The last time I lent it out, I was happy to see it returned to me with a large coffee stain on the back cover. These are wounds to be proud of, scars that show where the book has come from, where it has been, and who has cherished it.

Because of how much I enjoyed it, I shipped Monkeys to friends in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and California. I’ve gotten the novel back each time, and always with a few more cracks and creases. When I received the book in 2010, it was already well worn; at this point, there is a section of the book’s middle that needs to be held together by paper clip. The last time I lent it out, I was happy to see it returned to me with a large coffee stain on the back cover. These are wounds to be proud of, scars that show where the book has come from, where it has been, and who has cherished it.

This summer I am helping my parents move cross-country, from New York to Northern California, and I’ve been charged with organizing all the books in the family home. I imagine I’ll spend most of my time sprawled out among boxes, flipping through works I forgot existed, remembering those moments of magic when I first opened My Father’s Dragon, Jacob Have I Loved, or even Goosebumps. I’ll fit as many books as I can into as many boxes I can, and each book will start a new life 3,000 miles way. Those that I can’t pack I’ll donate, with the hope that they’ll be used and reused again and again.

So take a look at your bookshelf, and consider the history of its contents. Are your books gifts? First loves? Works you haven’t read but plan to? Works you’ve never been able to get through, though claimed that you have? Volumes that perhaps should have been returned but never were? Consider your books’ blemishes and tears with pride, knowing each defect to be a worthwhile moment in their lives. And the next time you pick out a volume, pause for a moment before you open it, and think about how it came to be in your hands.