by Kristin Brace

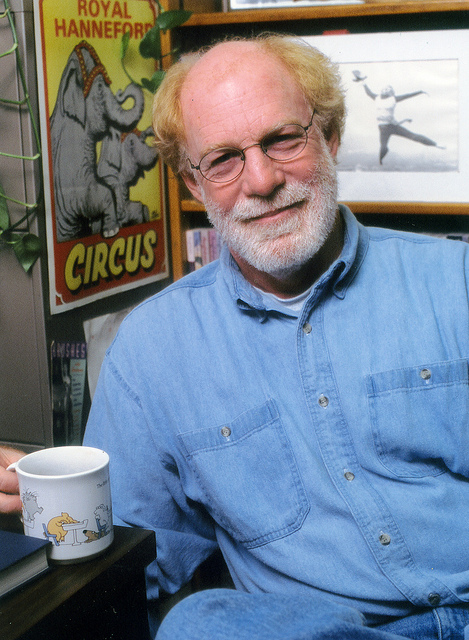

I met Jack Ridl on my first day of class as a freshman at Hope College in Holland, Michigan. It was Poetry 255 and we were in “The Dungeon,” a windowless basement room meant to serve as proof that poets could find inspiration anywhere. And inspiration we young poets found, if not in ourselves or our surroundings, then in the encouragement and guidance of our teacher—not “Professor Ridl,” but “Jack.”

Ridl taught at Hope College for more than 37 years, during which time he played an integral role in the development of the creative writing program and published several collections of poetry, the most recent of which is Practicing to Walk Like a Heron (Wayne State University Press, 2013).

Our conversation took place in Ridl’s living room, filling both sides of an old cassette tape recording of Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw. Yo Yo Ma played in the background and Stafford the Clumber spaniel snored softly in his favorite corner.

Kristin Brace: Did you go into college thinking you wanted to be a poet?

Jack Ridl: I wanted to be a major league baseball player. That’s all I ever wanted to be. I played ball through college and I certainly realized that I couldn’t go on with that. I wanted to be a minister but what I learned from a professor was that I was confusing that with being a church minister. He said I shouldn’t be a church minister. And I thought wow, that’s fascinating; ministry is something that you can do even if it’s not in a church. Then I had four majors in college because I was really confused and it took me five years to get through. I graduated, and still had no idea.

KB: What were your majors?

JR: Philosophy, Psychology, Religion, and English. When I got out of college I took a job in the admissions office and took on the role of the sensitive male of the late 60s. You know, flowers in the hair and all that—the flower child, sensitive man. Anything that was tender and heartbreaking and sentimental, boy I went for it. I started writing these incredibly sappy poems. Then I started writing songs for [the poet Li Young Lee’s] sister. I wrote songs for her for two years and we were ready to have a recording—we’d done some concert stuff—when she came to rehearsal one day and said she was going to get married and asked if I would be in the wedding. But then she said that meant she wasn’t going to sing anymore, only for her children. Well, that just threw me for a loop because we’d spent the last two years writing and performing and I didn’t want to go through that any more. This is how pragmatic it was! I’d been reading some poems and I kind of liked them and I thought, I don’t need to go through this anymore, with getting people to sing, and bands, and recordings. All you need to write a poem is a pen and a piece of paper. So I jettisoned the musical career and started writing these poems. And then I thought, well, why don’t I learn a little bit about it?

There were a couple poets in Pittsburgh that a classmate of mine introduced me to. One of them was Paul Zimmer, and I asked him if he would take a look at my poems and give me some advice. I gave him a whole fistful of poems. We had lunch about a week later and he said, “My advice is that you need to start over. These aren’t any good.” So he started me all over again. He said that he would tell me when I’d written a poem. In five years I gave him this poem and he sat there and read it and then he said, “Poem.”

KB: Tell me more about Paul Zimmer. How did he influence you?

JR: He lives on a hundred and some acre farm in Wisconsin. He has a writing shack. All of the wonderful things about wanting to do this, he was a wonderful image of that. He loved books—he just loved to hold them! He was a sports fan, he was a down to earth guy, he had a blue-collar family background—all of those things were exactly what I needed. I came from blue collar, I came from sports, I had no intellectual confidence, and here was this shuffling, bumbling guy who did it all himself, too. He taught himself. And then there was the romantic stuff—he had a writing shack. He would go out every morning in the writing shack. I thought, I want a writing shack. He was salt of the earth, and benevolently honest. He taught me to be a working class poet and I’ll always be that. I sit down and I go to work.

KB: Your poems have that everyday feel about them.

JR: A little bit of that comes from William Stafford, who was my other main teacher, and his great description of writing: “A reckless encounter with whatever comes along.” Exactly what you do is exactly what you can be dismissed for. You write about the everyday and people say, “It’s wonderful, he draws my attention to what I just pass by everyday,” or you flip it over and say, “The guy has no big themes or aspirations, these are inconsequential poems.” While the dismissive stuff stings, I’m not surprised by it anymore. That was a big thing to learn. Early on, I thought, you write five words and everyone passes out and puts a laurel wreath on your head. And I had to learn that for everyone who loves T. S. Eliot, there are people who are going to say, “He’s arrogant, who does he think he is.” For anybody who loves William Stafford, there’s going to be someone who says, “Oh, he’s just an old grandfather saying cute things.” You’re kind of helpless when it comes to responses to what you do.

JR: A little bit of that comes from William Stafford, who was my other main teacher, and his great description of writing: “A reckless encounter with whatever comes along.” Exactly what you do is exactly what you can be dismissed for. You write about the everyday and people say, “It’s wonderful, he draws my attention to what I just pass by everyday,” or you flip it over and say, “The guy has no big themes or aspirations, these are inconsequential poems.” While the dismissive stuff stings, I’m not surprised by it anymore. That was a big thing to learn. Early on, I thought, you write five words and everyone passes out and puts a laurel wreath on your head. And I had to learn that for everyone who loves T. S. Eliot, there are people who are going to say, “He’s arrogant, who does he think he is.” For anybody who loves William Stafford, there’s going to be someone who says, “Oh, he’s just an old grandfather saying cute things.” You’re kind of helpless when it comes to responses to what you do.

KB: Who were you most influenced by when you first started writing?

JR: When I started, I used to put Nancy Willard, William Stafford, and Naomi Shihab Nye’s books right here, right beside my chair, and that’s how I’d write. They’d be saying “yes”—I needed to hear yes. They wrote for the reasons I liked, all three of them.

KB: How did you get to know the writer Ellen Bryant Voigt?

JR: Years ago I started the Visiting Writers Series at Hope. I came across this foundation that would send a writer for a couple of weeks to a college and on the list was Ellen Bryant Voigt. I thought, she’s a master teacher, she invented the Warren Wilson program—she’s the mother of them all! If she came here and she liked it here, she could put us on the map for students. So I wrote this grant to see if we could get Ellen to come here and she came. She scared the hell out of me. Right away, the first time we met, she walked in, and she looked at me and said, “I understand you’re a Staffordian.” I thought I was over all my naïveté, and I couldn’t imagine anything being wrong with William Stafford— he was Christ come back as Bill Stafford as far as I was concerned.

Ellen spent two weeks here. She tore apart a bunch of my poems. She was up till two in the morning with the students night after night and she was just as tough as nails. But she was also “Aunt Ellen.” She was like that aunt who says, “What the hell’s the matter with you?! Put a scarf on, it’s snowing out there.” And she’d take those poems and boom, it was like taking them to the car shop, she’d fix them in ten minutes. She got mad about Paul Zimmer: “Five years!? Oh, that’s crazy. I could’ve taught you to do this in an afternoon!” She’s very southern when she talks to you like that.

About the end of the first week, the Staffordian and the Ellen Bryant Voigt came together. I got to indirectly suggest to her that there’s another way to look at this. In reference to my chapbook she wrote to somebody, “Jack is our poet of joy.” I didn’t know how she meant that, but then one time we were going up to another place for her to give a reading, and she said, “You know what strikes me today is that the most subversive, cutting edge thing you can do with poetry is to deal with joy. I just think that would be incredibly difficult.”

KB: I read an old review that looked down on the “acute specificity” in some of your poems. The idea was that it’s hard to reach a general audience with a poem that’s very specific. Could such a poem actually be more inviting than isolating?

JR: Two of the great things that any art does are to help people feel less alone—they relate to it or it relates to them, or takes them to a place they wouldn’t otherwise go. I think that review is interesting because he was praising both those books as the best books of the year but he said they didn’t extend, that it was like watching someone’s family slide show for an evening. If you read a novel about a family, that’s like a family slide show. It seemed like he felt like the thematic side of the poems didn’t have enough reach, they didn’t extend out, that it wasn’t universal enough in the human condition part of those poems.

His complaint was one that has been registered since the emphasis on the personal history poem started in America. American poets have been into the personal history poem for a long time. Now it’s shifted to the memoir; everyone goes to grad school to write their memoir. And that really is an extension of the poet writing a personal history. I think the complaint is that the poets have abandoned the big history, the big themes. But the reaction that started that movement was that the big history had pulled everyone away from learning about their Uncle Lou and their grandma. It had destroyed personal history. You often hear complaints about “Americans don’t know history.” What’s ironic is that they know even less of their own history.

KB: You published a chapbook called Outside the Center Ring that explores a rich part of your family’s history. Could you talk about the role of the circus in your work?

JR: My mother was raised with a cousin so they were like brother and sister. Cousin Albert, when I came on the scene, took me in. My father was overseas in WWII and Cousin Albert was a circus man. Circuses were in his blood since he was little. He ended up owning a circus—they had to be tent shows, not shows inside buildings. It’s a whole world. So when I was a kid during the circus season, primarily during the summer, he and I would travel around and do circuses. He knew everybody. So I was always behind the scenes. In the sports world I was behind the scenes with my father and in the circus world, I wasn’t watching the show, I was always in the back lot or hanging out with the elephant trainer after the act.

JR: My mother was raised with a cousin so they were like brother and sister. Cousin Albert, when I came on the scene, took me in. My father was overseas in WWII and Cousin Albert was a circus man. Circuses were in his blood since he was little. He ended up owning a circus—they had to be tent shows, not shows inside buildings. It’s a whole world. So when I was a kid during the circus season, primarily during the summer, he and I would travel around and do circuses. He knew everybody. So I was always behind the scenes. In the sports world I was behind the scenes with my father and in the circus world, I wasn’t watching the show, I was always in the back lot or hanging out with the elephant trainer after the act.

Paul Zimmer encouraged me to try not to write about something, but try to be as receptive as you can all day long, and allow everything to come in and eventually it comes out. Almost every poem is written that way. These two sequences are simply all that material that came out from childhood, the sports and the circus. And what I like so much about that is neither of them are first person. In both of those worlds that I work with, it’s all about the circus people, or the kid on the bench who never gets in a game. I really like the relief of self-consciousness.

KB: In an address to Saugatuck High School seniors in 1978, you talked about not always having the right answers but asking the right questions. What are some of the questions you ask? Or that you think students should be asking?

JR: I don’t recommend that students do this. I’ve had to transform “hopeless” into “it’s okay.” My questions tend to really hurt me. Maybe you’ve been there. They tend to be: “Who cares?” “Why bother?” “What’s the use of this?” It’s tough writing poems, psychologically, in our culture. I’ve got buddies who get up and know that someone wants them to paint their house. And part of that is the blue collar talking. Blue-collar people are haunted by the pragmatic—it gives you self-assurance. So when you’re doing something you know is not in real demand and yet you believe in, my questions tend to be not healthy. The questions that I think are good to ask, especially as students, would come out of my 355 class where we read Letters to a Young Poet in which Rilke talks about living the questions. They’re the questions that lead you to become more understanding and humane rather than judgmental.

KB: I remember Heather Sellers teaching her students at Hope College to write “ from the thorax.” From where do you write?

JR: In the 60s, James Wright, Robert Bly—those poets called the “deep image” poets—would write deep resonant images and you could tell the difference between those and the ones that were merely descriptive. There’s something about them that’s really real—they show up on the page—they shimmer, they’re alive. I can’t explain it. I want students to have it. It’s a very benign thing, even if it’s scary. It’s empowering, and they get in touch—it’s real in there. We’re not an inward culture. There’s a great misunderstanding of that being equated with self-centeredness or egotism. It has nothing to do with egotism. In fact, it’s when my ego goes away, when I’m least selfish.

KB: It’s interesting that inwardness is a part of many religious traditions. We live in a very religious place and I don’t think that this is a prevalent mindset here at all.

JR: No, and that makes it very difficult for us, raised in a Christian tradition because it’s quite skeptical of that whole business, even though it’s not right to be. There’s a marvelous Christian tradition of inwardness. That’s the story I always tell at the end of my class, about my daughter telling me when she was little that the most important word in the world is “with.”

KB: I think we inherit that burden of guilt, that anxiety that we have to get things done—schedule, schedule, schedule—and it eats away at all of our creativity and everything that’s so important.

JR: The wholeness and the holiness, it’s a real thing. You can tell all that institutional things are involved in are predicated on the opposite of what we’re talking about: “How can we get them to do this? How can we get them to…How can we get them to…” My method is how can I help people put the product aside and find what it’s like to go to that place and write a poem. And if the end result is shlop, that doesn’t dismiss this wonderful chance you had to be with your Aunt Sally in the poem world.

KB: Some of your poems have a sort of magical realism to them. Do those tend to come from a different place? For instance, are they rooted in early memory, or do they come from dreams, or do they just have to do with where you’re writing from that day?

JR: There are two forms of magical realism. There’s infusion of the supernatural with the natural and then there’s more what my work is closer to: it’s more the way I see things. I didn’t have much separation between imagination and reality when I was younger. I think some confuse it as an escape from reality and I don’t think that’s it. I see it as an entrance to reality. An escape from reality is hallucinating. If there are stories in it, it’s real to me.

KB: There are several references to jazz and blues in your poems. How does music inform and influence your work?

JR: The blues is incredibly important to me because the blues is singing the blues. That’s why it’s so fascinating to me. It’s not about being happy; it’s about keeping going. It’s about going on. I wake up in the morning with the blues! And then I just start singing and laughing and telling jokes and whatever it might be. There’s a wonderful paradox about blues singers. They’re almost more alive than those who merely have the blues. When you sing the blues, it’s a whole other metaphor.

KB: There’s more power in it.

JR: Yes! And I think a poem is that way. I think somebody reduces them to what happened. Sometimes a student will say, “Sorry my poem’s so depressing,” and I always say to them, “Your poem is not depressing. What happened, yes—I’d never disrespect the tragedy. But you made a poem!” I see it as a transformation of that experience into a poem.

KB: Do you feel especially close to certain poems you’ve written?

KB: Do you feel especially close to certain poems you’ve written?

JR: I never really have. My poems are all results, not goals for me. I like that place that you’re in when you write. It’s meditative, like deep prayer. This is Yo Yo Ma playing right now. How could you not want to do anything but feel yourself inside while he’s playing? You couldn’t write a paper on it. Anything else would be a reduction. It takes you past words. I think for me the poetry I respond so strongly to is words doing that paradox: the words take me past the words.

Jack Ridl is an award-winning author, most recently of Practicing to Walk Like a Heron (Wayne State University Press, 2013). Other collections include Losing Season (CavanKerry Press, 2009) Broken Symmetry (Wayne State University Press, 2006) and Outside the Center Ring (Puddinghouse Press, 2006). Ridl is a Professor Emeritus of Hope College in Holland, MI. More than seventy-five of his former students are published authors.

Kristin Brace received an MFA in Writing from Spalding University. Her writing appears or is forthcoming in Meridian, The Louisville Review, and The Rapidian, among other publications.