By Colorado Review Associate Editor Sarah Lin

A few months ago, while in the middle of production for the Spring 2011 issue of Colorado Review, I was delighted to find myself reading for the first time Floyd Skloot‘s nonfiction piece “The Famous Recipe.” The essay details Skloot’s exploration of an intriguing, never-before-seen recipe authored by his mother, opening with these paragraphs:

She might as well have said she had a photograph of my mother turning cartwheels on the moon. Instead, and no less implausibly, Joan said she had a recipe my mother contributed to a cookbook in the late 1950s.

Joan had been my brother’s fiancée forty-seven years ago and knew my mother never cooked. She may not have known my mother used the oven as an extra cabinet for stashing pots, pans, platters, and dishes, all wrapped in plastic, but she knew how unlikely it was for her ever to have prepared a dish called Veal Italienne “Sklootini.”

Veal Italienne “Sklootini”! What more pleasing name for veal, sauce, and spaghetti? When I reached the end of the piece and discovered that Skloot had included his mother’s original, improbable recipe, I decided I wanted to make this storied dish myself—albeit the updated 2010 version, with the author’s tweaks and adjustments. “From the moment I saw the recipe, I felt I had to cook it,” Skloot wrote in his essay, and so it was for me as well.

(I urge you to read the rest of the essay here. Go on, I’ll wait.)

Channeling Floyd Skloot, I invited several members of the Colorado Review staff over to my apartment for dinner. And a few days beforehand, I went off to the supermarket to buy the ingredients.

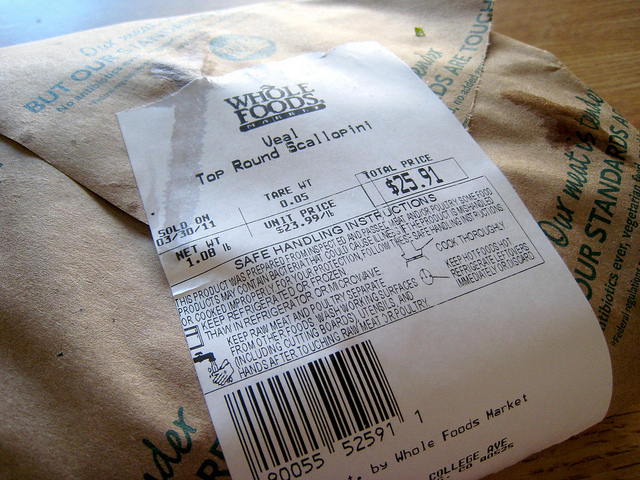

Most of the list was easy to cross off; the problem was procuring the meat. Local groceries don’t carry veal of any kind, and Whole Foods was sold out. I rang up several butchers in town, but my inquiries yielded nothing more than a series of regretful “no”s. I was about to investigate whether I could substitute thinly sliced beef tenderloin when I decided to ask Whole Foods if they would have in any veal the next day; Anthony, one of the butchers, offered to sell me finely cut veal ribeye (“even richer and more tender,” he assured me) for the same price as their veal scallops. And so, in the end, I got a bit of a bargain, though from a place where veal top round still rings up at $23.99 a pound.

With the meat finally obtained, it was time to cook. Skloot’s updated Veal Italienne “Sklootini” recipe calls for the dish to be gluten-free, but I took the liberty of reverting the recipe back to its roots in this aspect, using wheat flour and wheat spaghetti instead of the rice flour and brown rice pasta called for in his version. I left out the garnish of Parmesan, but kept the Kalamata olives, onions, red wine, fresh mushrooms, and fresh Italian parsley that were Skloot’s additions to his mother’s 1958 recipe. And of course, I declined to cook the veal as originally suggested in the 1958 version, fearing, like Skloot, that I would simply end up ruining the meat.

Therefore, what I placed before my friends was partly Skloot’s recipe and partly his mother’s—a huge platter of cooked spaghetti ladled with a rich, chunky tomato sauce, and over it the floured-and-seared pieces of veal ribeye, which had hit hot olive oil in a cast iron pan for about thirty seconds on each side and which had subsequently filled my entire kitchen with meaty smoke. I sprinkled parsley on top instead of Parmesan, and garlic bread and a green salad tossed with balsamic vinaigrette rounded out the table.

Inevitably cooking from any recipe is an act of making it your own. As my friends and I dug in, I thought to myself that were I to make the dish again, I’d season the veal with salt and maybe pepper before searing it, as to me the meat seemed slightly bland. I’d also leave out the cubed green peppers, because I’d forgotten that I actually don’t like them very much. But everything else, I’d prepare in exactly the same way, because it was a good meal, a hearty and satisfying meal, and one that I felt was eaten in very fine company—not only that of my friends, but of Floyd Skloot, and his mother, too.

Sarah Lin’s personal food blog, Salty/Savory/Sweet, can be read here.