Book Review

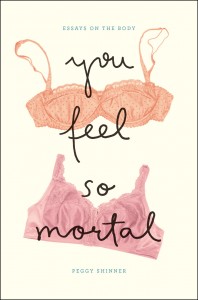

The popular conversation about women and our bodies has gotten dull. Yes, it’s a Barbie doll world. The media distorts reality. Girls aspire for a body that’s possible only in Photoshop. Anorexics. Boob jobs. Fad diets. Self-loathing. It’s become so familiar that I assumed I knew what to expect of Peggy Shinner’s first book, You Feel So Mortal: Essays on the Body, with its playful cover art of two bras: both pink, one decidedly sweet and sexy, the other a full-coverage, matronly model. But Shinner’s twelve remarkable essays are anything but the usual fare, instead taking as her subject the complicated relationship between our bodies and our souls.

The popular conversation about women and our bodies has gotten dull. Yes, it’s a Barbie doll world. The media distorts reality. Girls aspire for a body that’s possible only in Photoshop. Anorexics. Boob jobs. Fad diets. Self-loathing. It’s become so familiar that I assumed I knew what to expect of Peggy Shinner’s first book, You Feel So Mortal: Essays on the Body, with its playful cover art of two bras: both pink, one decidedly sweet and sexy, the other a full-coverage, matronly model. But Shinner’s twelve remarkable essays are anything but the usual fare, instead taking as her subject the complicated relationship between our bodies and our souls.

Shinner is in her sixties and like so many of us still struggles to be at peace with her body, with all its slouchiness, its “Jewish feet,” its bosom in need of ample support. Yet, she has gained the maturity and wisdom to take pride in her body, too. After all, she couldn’t get around without it. She couldn’t be a martial arts expert without it. She wouldn’t be Peggy Shinner without this particular corporeal form. And in each essay she wittily argues that our bodies forge our identities, with proof from her own experiences and those of the beloved people in her life: her partner, Ann; her clutch of loyal friends; her mother and father, for whom she still mourns decades after their deaths.

Shinner weaves these personal narratives with curious snippets of history on subjects as diverse as the mythology of women’s hair, the 1950s cult of good posture, and the fate of Nathan Leopold of Leopold and Loeb fame. These interludes of historical curiosities are entertaining, but also elevate Shinner’s personal memories to something more universal. Take “Pocketing,” for example, in which Shinner recounts her single experience of shoplifting—a can of nutmeg from a grocery store back in her twenties—in contrast to nineteenth-century notions of women’s psychology. Women, the old theories went, became kleptomaniacs because of troubles with their wombs and their repressed sexuality. And while we are enjoying this romp through an earlier era—those crazy, sexist psychiatrists!—she asks herself whether, in fact, those ignoramuses might have been onto something. Wasn’t it true that when she shoplifted she was in transition, having proclaimed herself a lesbian but not yet having found a partner with whom to consummate this newly declared sexuality? Her voice shines through as she tells us about her theft:

I stole a jar of nutmeg from the Jewel. . . . Where I had gone grocery shopping. Where I had, in fact, filled the cart with my small stash of weekly necessities. I was the occasional baker, and the nutmeg, I dimly reasoned, could be used in zucchini bread. I concealed the jar in my pocket, which no sooner hidden there seemed exposed, and waited in line to pay for the rest of my groceries. . . . It was a down-at-the-heels Jewel in a modest neighborhood. Many of the shoppers were Latino. I was a diffident white woman not likely to catch anyone’s attention. I left the store unnoticed.

…

Did I steal the nutmeg as a substitute for sex? Was the desire to be transgressive really the desire to fulfill desire? Did I just need a little nookie? Well, I did need a little nookie, there’s no denying that.

In Shinner’s deft hands, the factual bits woven into her essays feel as organic and essential as her personal stories and reflections. Reading her work is, I imagine, akin to sitting next to her at a dinner party: her ideas a sparkling confluence of anecdote, self-analysis and quirky historical facts.

For Shinner, any discussion of the body must also be a discussion of being Jewish, the two being intertwined in her identity. “History has weighed in on my body, and I have come up . . . Jewish.” I confess that as a mutt of nineteenth-century Ellis Island immigration, my body has never been a strong source of ethnic identity. I have never considered whether my too long nose or my stocky legs are particularly Irish or German, whether others might evaluate my body not just based on its beauty or lack thereof, but on its ethnicity and, thus, assume a package of other traits for me, too. Shinner dissects her love-hate relationship with her stereotypical Jewish bodily traits—her flat feet, her slumping posture, her nose before it was reshaped by surgery—and explains how this tension is central to her sense of self. On one hand, she has pride in her “tribe,” to use her word, and a desire to be recognized as a member of it: She’s resentful when a colleague says, I didn’t know you were Jewish. On the other, she considers the benefits of assimilation that her decidedly gentile name and newly minted snub nose may have granted her, among them, the choice of when and whether to disclose that she is Jewish. “Sure, I want to be taken for who I am, but . . . I don’t want to suffer too much for it.” But Shinner wonders both if there is disloyalty in this assimilation and what price she pays for it. “Anonymity lets others fill in the blanks.”

While the first section of the book is devoted to essays about Shinner and her relationship with her own body, the second section shifts the focus to the bodies of others: Shinner’s mother, who survived breast cancer only to die in her fifties from thyroid cancer; her father, who died after a stroke when Shinner was in her late thirties; and her great-aunt, for whom Shinner had responsibility as the depressed elderly woman neared death. Shinner struggles to understand the relationship between these failing bodies and the souls that they sheltered. As she says in an essay on the disconcerting autopsy of her father’s body, “Postmortem”:

I feel loyal to my body. It is, for better and for worse, for all its betrayals and my abuses, mine. I imagine a final leave-taking, when death comes, and body and soul part ways: Bye-bye, the soul might say to the body…. And the soul takes off. And the body is at rest.

In these smart and engaging essays, Shinner challenges us to reconsider our bodies—in particular women’s bodies, in particular Jewish bodies—but her point is more general, too. Our existence is intricately linked to our ongoing physical health. No matter how much we malign how our bodies look or function, how they regularly disappoint us, we cannot exist on this planet without them. Throughout the collection, Shinner employs a funny, self-deprecating tone as she tells some of the most embarrassing, intimate, and hilarious details of her life: her teenaged nose job, the degradations of a bra-fitting, guiltily eating pigs-in-a-blanket on Rosh Hashanah, her obsession with choosing the just-right burial plot for herself and her partner. Her willingness to share these most private moments with us gives her authority when she shares, too, her wisdom and insights. She stands naked before us, both in body and in mind, fully exposed, fully vulnerable, fully human.

About the Reviewer

Jennifer Wisner Kelly’s stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in the Massachusetts Review, the Greensboro Review, the Beloit Fiction Journal, Poets & Writers Magazine, Colorado Review, and others. She has attended residencies at the Jentel Foundation, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. Kelly is the Book Review Editor for fiction and nonfiction titles at Colorado Review.