Book Review

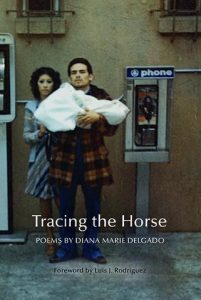

In her strong, debut poetry collection, Tracing the Horse, Diana Marie Delgado comes to terms with cultural forces that limit her, especially those of machismo—as in “Songs of Escape” where “Men are the only islands / I’ve ever lived on. / I’ll never get away.” Delgado, though, doesn’t back down. Starting in the first poem “Little Swan,” the speaker-poet has this urge “to understand the drive // to hurt something young, / wild with sky.” There’s this insatiable curiosity about violence and violation, which is inherent in this masculine world.

There’s lovely varied pacing in this book, which is its one of its strengths. Almost half the poems are compact yet spacious with one or two-line stanzas, and they usually spark in the fireworks of emotional and linguistic resonance, such as in “They Chopped Down the Tree I Used to Lie Under and Count Stars With”:

Inside the Impala’s trunk: clubs and maces.

I’m kissing a boy in his car, below a streetlamp vibrating with moths.

I pretend to lie in sand, be part ocean, dust from a candy cigarette.

Spanish feels like eating roses sprinkled with lime;

English, peeling potatoes, barefoot.

The pacing and associations drive these end-stopped monostich lines, and they counteract the fragmentary feel of a list. In this poem, and others in this collection, the sharp, piercing form seems to cue a male energy (mostly associated with violence) in Delgado’s perception of her world.

In sharp contrast, about a third of this collection are prose poems that are usually shorter, bare, and more prosaic, as in “Amiga”:

We were in front of Kmart when I called your boyfriend an asshole for beating you up and you told me if I said anything bad about him again, you’d never speak to me.

Only one pause in this long-sentence poem, the part that threatens to chop off their friendship. The intensity—the violence that a language enacts or passion it evokes—seems absent or more contained. Rather, the language here seems more stretched, syntactically complex, and emotionally nuanced. This form seems to cue more of the female energy in Delgado’s perception and enactment of her world.

Throughout the book, there are glimpses of violence, poverty, and addiction. Despite living in this world, Delgado finds spaces that defy machismo’s constriction and erasure. In “Lucky You”: “All absence is large, / a stretch of spine you can / never touch.” The implication is that “you” cannot hurt her even if she does not have a rigid strength of backbone, usually associated with male energy. There’s strength here is in its stretch and hiddenness.

While men are a threat, though, Delgado has love for them, too. There’s tenderness towards her brother and father. For instance, during the Day of the Dead celebration in “Where I Drown”: “There are games to play / . . . But my favorite / part that’s taught, // is that Dad / never stops.” Delgado does not dwell on violence and violation. She juxtaposes, steps in and out of this masculine world. She has complexity and agency.

In the middle section of this collection, two powerful monostich poems with their single-line thrusts seem to open up the speaker-poet’s agency. “In the Romantic Longhand of the Night,” women have power in coarse and almost violent sexuality: “Let’s kneel on gravel, tear apart the lace // of fruit, blade the wool from lambs // who kiss hard, eat the meadow’s changing face.” The female speaker-poet gathers in and uses this male, violent energy. She concludes:

Let’s fake it the right way, draped in the right light

For the wrong person. Although we say we aren’t,

We’re seeking the tricky algorithm

Of travel, boys who wager swans first

And survive on cobwebs and capture.

At her best, Delgado is precise in language and brilliant in her associations and tensions.

Her next poem “Prayer for What’s in Me to Finally Come Out” continues this momentum, not as sexual, but cultural defiance—no longer hiding, she is revealing all the seemingly disparaging parts of her heritage when growing up. The infinitive in the title is split—it’s non-conforming grammar in the dominant white-male literary culture, just as this revealing poem is an aberration or underbelly in the dominant American culture in which she lives. This poem lets readers know the difficulties in her family: drug addiction, lower-class poverty, and her brother being shot. Her female strength emerges via the male energy of the monostich form. This poem claims her space. Though vulnerable just by revealing her life, she garners the curiosity of a young and perhaps frightened girl who dreams (as in her first poem “Little Swan”) and transforms it into plain observation. There are no poetic niceties, only brutal observation.

Everywhere the white American culture presses into the speaker-poet’s world. In the next poem, “Notes for White Girls,” “Roaches bubbling out of drawers and cabinets, [. . .] Life as a girl in a Mexican family can feel different. Sometimes like you’re not part of the family.” She uses a language hiccup of white Valley girls (“like”) to counteract the stereotype of Mexican families (as roaches). She, too, has grown up in the valley. She is both a part of this culture and not. Delgado inhabits both spaces—that of white California Valley girls and machismo. And as a Mexican-American woman, she feels trapped, as in “Songs of Escape”: “Our house: two doors, / a window that never opens.” What saves her from being stuck? At the end of this section in “Dream Obituary,” she seems to answer: “my journey is to forgive / everything that’s happened.” Perhaps, then she can truly be who she is.

What does it mean to be herself in this Mexican-American culture? The last section moves more toward answering this question. The first poem, “Who Makes Love to Us After We Die,” is a prose poem where “I turn on the radio and hear voices, girls becoming women after tragedy. Talk about dreams!” This opening starkly contrasts with the first poem of this collection, “Little Swan,” where “Most nights I’m face to face with the stars. / No one is more afraid of this than me.” Afraid, she cannot look at whatever the stars tell her, which likely indicate the reality of where she is and what her dreams have become. In this prose poem, though, the speaker-poet has evolved into herself. “I found a recipe he’d carved into the wood, and I had a hard time believing him.” The speaker-poet has choice. She’s making up her own mind about what she encounters, not wondering why but taking what she found into herself then deciding whether or not to believe a man. This older speaker-poet has power and agency. The section ends in the location in which the speaker-poet seems to have grown up. In “La Puente” (“The Bridge” in Spanish), while the form has male monostich energy, the lines are longer, not just one independent clause, perhaps reaching toward Delgado’s literary cue of female energy. “I lived next to a train crossing on Valley Blvd, the sky above pink-and-gold stars. / Summers were horses traced on denim; my youth unfolding, paper fan.” She is there, choosing to be under the stars in this violent imposing world, which this poem reflects throughout (drugs, crime, prison, gangs), yet she’s herself and not afraid anymore.

About the Reviewer

Robert Manaster has published poetry book reviews in such publications as Rattle, the Los Angeles Review, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and <>Massachusetts Review. His poetry has appeared in numerous journals including Birmingham Poetry Review, Image, Maine Review, Into the Void, and Spillway. His co-translation of Ronny Someck's The Milk Underground was awarded the Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation.