Book Review

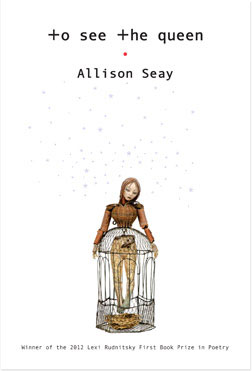

“It is too simple to say the figment is inside me or is myself, / or whichever of my selves, in some thick air. / Or even to say the figment is an illness.” So begins “Sick Room,” from Allison Seay’s To See the Queen, winner of the 2012 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry. The “figment” haunts this haunting collection. The figment is depression, sickness, desolation—and yet, as “Sick Room” explains, it cannot be reduced to those labels.

“It is too simple to say the figment is inside me or is myself, / or whichever of my selves, in some thick air. / Or even to say the figment is an illness.” So begins “Sick Room,” from Allison Seay’s To See the Queen, winner of the 2012 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry. The “figment” haunts this haunting collection. The figment is depression, sickness, desolation—and yet, as “Sick Room” explains, it cannot be reduced to those labels.

Though these are poems of frightening interiority, the self in Seay’s work is not exactly self-contained. Much of the book hinges on a figure, a figment, named Liliana. Liliana is with the speaker, in some ways is the speaker, and yet remains apart. As Seay explains in an interview with Persea Books: “Liliana is, by turns, love, God, sadness, mercy – variations on a theme of psychic questions and discoveries. She is both blessing and curse…I never thought of her as less than a fully human and alive being. She exists, even if only in an imagined reality.”

Seay’s speaker suffers intensely, and is intensely self-aware. Take a poem like “Room of Sleepwalking,” in which Liliana figures prominently:

I was being drawn

creme and black from the mouth up.

Liliana painted my sadness with a flue-black streak

on the canvas where my brain would be.

Though Liliana is in some ways a creation of the speaker’s, the speaker has come to feel that it is Liliana who creates her. Liliana’s act is at once tender and troubling: she carefully renders the speaker, and understands her sadness intimately. In doing so, however, she erases the speaker’s brain, and all of her body below the mouth. The poem continues:

I understand now it was she this whole time

mixing colors in the sink; she who polished the silver

with a scarf while I slept,

she I heard humming with joy

As Liliana becomes responsible for more and more of the speaker’s daily experience, we begin to suspect that Liliana is the speaker—alienated from her own experience, the speaker sees herself as sleeping while some other self goes through the motions of her life. Perhaps the speaker is being drawn in a self-portrait. As the poem continues, however, Liliana becomes so distinct from the speaker that this initial reading can no longer quite hold:

and she, lamp-tanned at the bedside while I writhed,

who told me of a lovely other world: where

everything is a shade of green, where I find my bracelet

in the wheatfield and a red fox in some enormous woods.

Liliana sits vigil with the speaker through her illness, comforting her. The comfort she gives the speaker is a product of the speaker’s life—Liliana’s knowledge of the lost bracelet indicates an intimate familiarity with the speaker’s most quotidian concerns—and yet it goes beyond her life into a prophecy of fields and foxes. Though Liliana may be in some ways rooted in the speaker, she also sits outside her, transcends her. The poem continues:

She says to me

dear sleepwalker, dreamer, darling sufferer,

next time you will find whatever

you are after. Next time the kitchen is only

a sunny kitchen, the room where my brushes are drying,

and never again the room with the knives.

Though we are reminded that the speaker is a “sleepwalker,” raising again the possibility of Liliana as a kind of alienated self, Liliana’s string of epithets and emphasis on their twoness (she says to me) further cements their separation. Liliana becomes a voice of hope, even salvation—the speaker’s freedom from the kitchen-as-room-with-knives (implicitly, her freedom from suicidality) is possible only by means of the assertion of the kitchen-as-room-with-Liliana’s-brushes. Liliana’s painting, her remaking of the speaker—a remaking that erases the speaker’s mind—becomes, paradoxically, the speaker’s chance to continue to exist.

There is much more to say about Liliana, whose presence dominates the book, and whose role shifts and develops frequently. When, in “Room of Resignation,” the speaker at last does “something [Liliana] could not forgive” (implicitly an attempted suicide causing severe self-harm), and Liliana abandons her, we have come to rely on Liliana so much that the loss is staggering.

Given the constraints of the review, however, I want to turn my attention to another vein of Seay’s work, her poignant handling of fraught romance. Though the second section of Seay’s book, “Geography of God’s Undoing,” fits well within the context of the volume as a whole, the section is so strong that it could easily stand alone as an excellent chapbook. The section charts the course of a failing love in vivid, unexpected ways. Take “My Husband, the Roe”:

Before the joy there was the end before the end

the ugliest before the worst before I said no

before he asked me to marry him before

I wanted him to ask me before he loved me at all

before he knew I moved to town before I moved to town

I had to move before I had nothing

……………………………………..

before I knew my name before

I had a name before I was born

he was born already

By tracing each step of the romance further and further back, Seay creates a haunting sense of inevitability. The speaker traces this thread into the past not out of a desire to get back to an earlier, happier time, but rather in order to make sense of a cause-and-effect chain that she could not possibly have perceived until now. Even before she had a name, the speaker’s life was leading toward its present. Even more hauntingly, before her birth, “he was born already”—even before the speaker existed, the chain of events had been set into motion.

Once again, there is much more to be said about these poems, and not enough time to say it. Suffice to say that To See the Queen is a masterful book. Seay takes big risks—an extreme interiority, an unrelenting sadness, the complex and multifaceted uses of Liliana—and they pay off wonderfully. These are frightening, moving, deeply human poems—poems such as these are sorely needed.

About the Reviewer

J.G. McClure is an MFA candidate at the University of California – Irvine, where he teaches writing and works on Faultline. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in various publications including, most recently, Fourteen Hills and The Southern Poetry Anthology (Texas Review Press). His reviews appear in Green Mountains Review and Cleaver. He is at work on his first book.