Book Review

In the 19th century,

People believed that emotions

Came from the heart

But now we know

That they come from the brain—

Emotions, and that helps us to—

In these Dickinsonian dashes are all the difficulties and puzzlements that we still retain in the 21st century when we consider the heart. Claudia Keelan, in O, Heart, has written a poetic treatise on the heart, encompassing the past, the present, and the timeless fantastic; a time machine for anyone who has a heart.

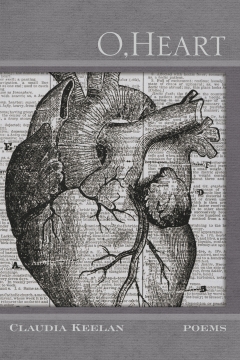

The title O, Heart tips the reader immediately that this will be a work that considers historicity as well as an address to/about the heart. The cover art, by Diane Cundall, is a print of a historical anatomical drawing of a heart superimposed on an H page of the OED. And no one today spells the word “O” without an h. The text itself interweaves the 16th through 21st centuries (with a few others thrown in for good measure; Keelan is a scholar of 12th century women troubadours) the characters acting out, in the form of a play within the book and sometimes through the poet’s voice on the periphery of the play, what it means to be a woman, an artist, a mother, a daughter and a spouse. Always present, too, is the poet’s engagement with the history of literature: words and phrases that describe and often ignite the heart. The wealth of references (Shakespeare, Whitman, Dickinson, Hawthorne, Jane Bowles, etc.) will awake echoes in the reader’s mind and leave her hastening to rediscover these writers in the light of the characters’ reimagined lives. Readers who enjoy looking deeper into the text will find other rewarding literary references as well. Keelan uses historical personas to look at the psychological anatomy of the heart: William Harvey, discoverer of the heart’s circulatory system, Jane Bowles, Emily Dickinson, Kate Chopin, the Brontës and Poe, as well as a number of literary and allegorical characters, among them, interestingly, Pity.

O, Heart’s told slant; in this case, through the exploration of the many meanings of “heart” and through the hermeneutics of a personal and specific life, which, as Keelan has observed, is representative of all lives. The book includes a play, and even outside the play, many poems have titles that allude to playwriting, such as Scene 4, Act 2, giving the sense that the theater of the heart also acts outside the prescribed limits of form. William Harvey, both in the text and in the play, acts the part of both the scientific mind and the mind in the mind vs. heart dichotomy, still a powerful metaphor in this day and age. The repetition of the description of the functions of the heart’s chambers, in the play and elsewhere in the text, almost turns Harvey’s dry text into a lyric itself: “Two hold the blood / Returning to the heart and at just the right moment, empty.”

The play in the book has been expanded and in fact, produced on stage at Black Mountain Institute. Keelan has said that after publishing the book, she felt pushed by the characters to continue the play. In the stage version, a “verse drama” is read by students in the Creative Writing MFA program and colleagues including the poet (and Keelan’s husband) Donald Revell; some parts from the book are expanded or additional material is performed (Shaky Girls) some parts are differentiated (poems read by a Bride not present in the book) and some poems are given a noted expansion in meaning by being read by two voices instead of one. In the play, both in book form and on stage, Keelan’s wit shows in her list of dramatis personae (not all of whom actually appear in the play, but certainly have informed the poet’s thinking about the heart): POE: ANTITHETICAL MAN OR THE AUTHOR’S AVERSION TO THE BAROQUE; EMILY BRONTE: ANTITHETICAL WOMAN OR THE AUTHOR’S AVERSION TO THE LITERATURE OF OBSESSION. Even the stage directions have a bite to them: “lyric poetry circles on ticker tape and the characters shout it out randomly like brokers.” Is this a barb at the commercialism of poetry, at the ubiquity and abundance of Love Poems (later referenced as the Oxford World Classic Love Poems)? The women in the play find these poems ridiculous in fully (or even partially, in the case of Robert Herrick’s Julia) describing the heart, perhaps as ridiculous as the monolithic scientific view represented by Harvey.

In two poems, each called “Continuous Acts,” and thus, possibly, still a part of the play, Keelan further explores what the heart might mean in terms of being a 21st century woman who is a daughter, wife, and mother, as well as an inheritor of powerful cultural mythological female figures: Lucy the Fossil, Sheela Na Gig, Mary, Mother of God, “armless Venus de Milo,” the Shekinah. In the second “Continuous Acts,” Keelan introduces the allegorical La Liberté, lady liberty, she of the welcoming heart, whose blouse is torn. The poem delves further into the symbols and metaphors for heart: “All the posturing / Synonyms want a role / In the play: Spirit core nature mood mind…” but this poem, perhaps the most recognizably “political” in the book, essentially describes a thinking, feeling lady liberty, and her meditation on her own destruction. In “(HIS)torical Heart,” Keelan gives us a central moment in the medical history of the heart and brings to mind those early 19th century paintings of the first surgical theaters, the men in their suits and ties:

The physician has removed

The mitral annulus

Which resembles a cross

It’s easy to see the logic

Why it’s right there!

Our heart in the crossbow

And so an anatomist

At a lectern above a corpse

Among students and gawkers

The subjective ruined opening

Up all around them.

In this poem, we can see again how science both relies on and is unaware of the power of metaphor. Perhaps here is a double meaning to the phrase “the knowledge of the heart.”

In the play as read, the character of Woman represents Everywoman in our time, and the gathering of characters represents nothing so much as a night out with the girls in a cabin somewhere, drinking and exchanging ideas and lives; but as in real life, the jokes and confidences in the conversations are not trivial, but meant to help us figure out how to live. The women characters, Woman, Jane Bowles, Emily Dickinson, and Pity, talk and read from The Scarlet Letter, as they mock, admire, and empathize with literature’s difficult heroine, Hester Prynne. The surreal enters in the form of the Stranger, a tormented man with a caul of moths, accompanied by William Harvey. Who is the Stranger? Is the Stranger a representative of those men who are faithless (as part of the performed play, Keelan notes that the Shaky Girls could be the wives who stand beside their lying politician husbands); is the Stranger a partner who has grown away? Or, is the Stranger “my Stranger,” the stranger that we become to ourselves over time?

Keelan has said that one of the themes in the book is infidelity, a neutral word that the poems belie, most especially in the lyric portions: In the second of two poems called “Mojave Letter,” “I am authentic / I break my own heart” resonates powerfully with any person who has both rejoiced and suffered in a relationship. But the word that comes to mind is betrayal, rather than infidelity. It’s deeply felt. Who is betrayed and who is the betrayer, other or self, other and self, is the question the poems and the characters in the play ask. Fictional characters such as Hester Prynne and Desdemona are used to explore this theme as are Jane Bowles and Emily Dickinson, two historical figures who broke their own hearts loving people who could not love them back. Keelan hints that there are other ways to break a heart; for example, wanting something back that has disappeared: a time, a feeling, a different self. Sometimes, in reliving our private histories, we break our own hearts.

What comes of these scientific and psychological explorations into the nature of the heart? In the last group of poems in the book, Keelan disputes da Vinci’s notion of the retrograde: “At one and the same time, in one and the same subject, two opposite motions cannot take place…” In “Agape, the Woman is Agape,” she says, “There are always at least two motions / Desire and repentance, love and hate / Staying home or leaving forever / Staying home and leaving forever.” Here, “The women inside the woman / The strangers inhabiting the man” are somehow givens that if we can understand, we can accept. The last poem in O Heart relates the “scientific” to Edna’s last action in Chopin’s The Awakening (from the poem “First Acts.”) Edna decides to swim out into the open water, “swimming away from possession / Swimming into the possession / Of her own heart / Which drowns her.” Keelan’s poem acknowledges the metaphor but is strangely hopeful for the future.

Retrograde Heart

Yes, da Vinci was wrong.

There is the reality of retrograde,

Which is motion in the opposite direction.

And though we are not, love, celestial bodies

Our hearts do there aspire.

swim swim

swim swim

O, Heart is a book I will go back to because of its mystery, its wit, in both senses of that word, and because of its moments of personal revelation and recognition. There are still things to discover. What is the meaning of the arrangement of poems/play? I have postulated that the poems titled in the language of theater are a way of breaking a theatrical boundary; but what is the reader to make of the poems with identical titles, placed apart from one another? In some cases, the titles themselves posit questions. What is a “Continuous Act”? What is a “Primary (not Prime) Directive”? In what sense is the word “Agape” used in the Agape, The Woman is Agape poems?

What is clear is that the book itself deals with intimate questions: the condition of being woman/human, the mistakes, the betrayals, the “continuous act” of figuring out how to live, and discerning what is most important to our “spirit core nature…”

I have called the book a poetic treatise, but in effect, it is more an inquiry into our particular hearts; to me, that is the essential function of poetry.

Published 2/17/2015

About the Reviewer

Carol Ciavonne’s poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Boston Review, Colorado Review, New American Writing and How2, among other journals. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Poetry Flash, Xantippe, Pleiades and Entropy. She is the author of Birdhouse Dialogues (LaFi 2013) (with artist Susana Amundaraín) and a collection of poetry, Azimuth (Jaded Ibis Press 2014; artist Beatriz Albuquerque). Ciavonne has also collaborated with Amundaraín on several theater pieces, and has worked with the innovative The Imaginists theater collective in Santa Rosa, California. cciavonne.blogspot.com