Book Review

In American poetry, the work of Russell Edson and James Tate epitomizes the type of surrealism that successfully combines mystery, tragedy, and humor (especially if your tastes already lean toward the absurd). Each poet left behind books that can move you as much as they can make you feel uncomfortable, at least in the sense that you don’t necessarily know how you should feel by the end of a poem. Any poet who takes up the mantle of surrealism has big shoes to fill, and Jose Hernandez Diaz is not just filling them, but creating a style that is unique, memorable, and uncanny enough to navigate an already strange world.

In American poetry, the work of Russell Edson and James Tate epitomizes the type of surrealism that successfully combines mystery, tragedy, and humor (especially if your tastes already lean toward the absurd). Each poet left behind books that can move you as much as they can make you feel uncomfortable, at least in the sense that you don’t necessarily know how you should feel by the end of a poem. Any poet who takes up the mantle of surrealism has big shoes to fill, and Jose Hernandez Diaz is not just filling them, but creating a style that is unique, memorable, and uncanny enough to navigate an already strange world.

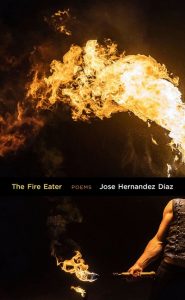

To read The Fire Eater is to put yourself in a reality that straddles the one we live in and the one where just a tiny change in detail makes us question what we thought of as reality in the first place. The title poem is relatively grounded in a world where a performer showcasing his “tricks on Hollywood Blvd by the entrance to the 101 Freeway” is exactly what you get (the language and narrative here is reminiscent of Franz Wright’s collection Kindertotenwald). But immediately in the following poem “The Fire,” Hernandez Diaz describes a man waking up to a fire in his building. The man breaks the window with a chair, but what awaits him below is unexpected:

A preacher was down at the bottom, waiting to catch him. He jumped into the preacher’s arms. On impact, they both transformed into pigeons. They flew away from the fire. Far away from the fire.

The pair could have changed into eagles, or vultures, or any other bird or animal Hernandez Diaz wanted, but he chose pigeons (scientifically identical to doves—symbolic of hope) and there is hope that the man survived his fall. However, one could say that the man didn’t survive (a three-story building is a considerable height for anyone), and the hope (doves) that we see here is merely our desires as readers for a happy ending. We can oscillate between interpretations all day long and still not be any closer to the truth, but herein lies the beauty of Hernandez Diaz’s poetry: what is real is up for grabs, and it’s our job to decipher what’s in front of us any way we can.

The first section prominently features a man who encounters new cities, clowns as targets, mimes, dragons, coyotes, and abandoned shores. The theme of regret shows up throughout, and nowhere is it more tragically revealed than in the poem “The Moon.” Characteristic of the man’s sudden predicament in previous poems, he wakes up on the moon. The man looks down at the earth, and what follows is a subtle, yet profound, reflection on missed opportunities:

He saw the earth in the distance. It looked like a blue and green tennis ball, only significantly larger. He remembered his childhood in California. How he wanted to be an astronaut when he grew up. Nothing could stop him now.

Nothing can stop the man because the man is no longer bound by earthly constraints (either because he is dead, is still dreaming—can we even trust that he woke up in the first place?—or because of some other reason we haven’t yet conceived). The man is full of hope and, in a way, we are inclined to believe his success reflects our possible own. (I mean, who doesn’t want to be unstoppable?)

The second section of The Fire Eater features “a man in a Pink Floyd shirt” and his absurd encounters and adventures, which lead him through unexpected house parties, subways, impromptu bands, and, of course, to the moon. Despite the plethora of images and scenes, Hernandez Diaz skillfully combines humor and moral inquiry within the span of a few sentences in order to show the complexity of human life. “The Hole” is emblematic of such an approach:

The man in the Pink Floyd shirt dug a giant hole in his backyard. Someone had told him to go to hell earlier that day. Assuming hell to be beneath the soil, the man in a Pink Floyd shirt picked up a shovel, and got to work. The person who told him to go to hell was a professional juggler. He juggled axes, bowling pins, and soccer balls. The man in a Pink Floyd shirt had accidentally bumped into him causing him to drop his soccer balls. That’s when he told him to go to hell. The man in a Pink Floyd shirt dug and dug. He told himself that when he got to hell, he would fistfight Lucifer. He didn’t much like his chance against Lucifer, but he thought it a nobler endeavor.

The man eventually falls asleep from fatigue, but his initial intention for wanting to dig the hole was rather honorable, regardless of what led him to his backyard in the first place. The speakers in many of Hernandez Diaz’s poems wants to remain as moral as they can, aware that circumstances will inevitably push them in a different direction or prompt them to question their place in other people’s lives and in the world.

By the time we reach the end of the collection, Death (represented by a skeleton) has replaced the man and the man in the Pink Floyd shirt and is parading through city parks, lakes, and the city of Los Angeles. The skeleton is rather reflective throughout the third section, and it realizes, like we all come to realize at some point in our lives, that it is time to call it a day:

It was a misty night. The skeleton sat deep in thought. His mother had taught him how to play when he was a young skeleton. She’d been deceased for a century. A crow landed on the piano as he played. The skeleton smiled at it. The bright moon floated above the sporadic clouds. The skeleton wore a scarf and fedora. When he finished playing, at midnight, he smoked a cigarette by a creek. He wondered when the time had gone.

If you have not yet wondered where all the time in your life has gone, then you surely will at some point. The Fire Eater ultimately tackles what it means to be human in a chaotic world, and how we can create meaning with the brief amount of time we’re in it. Provoking, thoughtful, and always entertaining, Hernandez Diaz has written a stellar book, one that no doubt will be prologue to his great works to come.

About the Reviewer

Esteban Rodríguez is the author of the poetry collections Dusk & Dust, Crash Course, In Bloom, (Dis)placement, and The Valley. His poetry has appeared in Boulevard, Shenandoah, The Rumpus, TriQuarterly, and elsewhere. He is the Interviews Editor for the EcoTheo Review, an assistant poetry editor for AGNI, and a regular reviews contributor for [PANK] and Heavy Feather Review. He lives in Austin, Texas.