Book Review

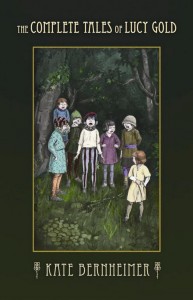

The Complete Tales of Lucy Gold, Kate Bernheimer’s third and final novel in the trilogy about the lives of the three Gold sisters, Ketzia, Merry, and Lucy, is a wild and lyrical romp through the mind of Lucy Gold and a fitting finale to this sometimes baffling series. Like Bernheimer’s other two novels, The Complete Tales of Lucy Gold is indebted to a variety of Russian, German, and Yiddish fairy tales which serve as springboards for Lucy’s own adventures and imagination. While the novel’s poetic impulses in the rendering of Lucy’s world and psyche occasionally lead the reader astray, it remains a beautifully lyrical and modern evocation that succeeds in shattering the mold of the typical fairy-tale world, all the while honoring it in spirit.

The Complete Tales of Lucy Gold, Kate Bernheimer’s third and final novel in the trilogy about the lives of the three Gold sisters, Ketzia, Merry, and Lucy, is a wild and lyrical romp through the mind of Lucy Gold and a fitting finale to this sometimes baffling series. Like Bernheimer’s other two novels, The Complete Tales of Lucy Gold is indebted to a variety of Russian, German, and Yiddish fairy tales which serve as springboards for Lucy’s own adventures and imagination. While the novel’s poetic impulses in the rendering of Lucy’s world and psyche occasionally lead the reader astray, it remains a beautifully lyrical and modern evocation that succeeds in shattering the mold of the typical fairy-tale world, all the while honoring it in spirit.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to speak of the novel’s plot. It jumps and shifts quickly between what seems to be the real world Lucy inhabits—working as an animator—and another, parallel world where Lucy resides in the woods, making dolls. Detailing the plot would also spoil the unfolding mystery that occurs near the end. The chapters of the novel work less as markers of time and progression and more as connected short stories or vignettes that create an overall picture of a troubled and perhaps traumatized woman struggling to cope with a terrible event or loss.

Throughout the novel, Lucy continually foreshadows or mentions her death; there is even a chapter titled “The Death of Lucy.” In this chapter Lucy places in her mouth “a small rock on the path that reminded me somehow of . . . my happy childhood.” When it lodges in her throat, Lucy tells us, although she thought she might end up swallowing the rock, “Instead, I died.” This jars the reader and instantly forces a shift in his or her view of the narrator, who now appears to be speaking from the grave. Yet, two paragraphs later Lucy reveals:

When I woke up, the doctors said that I had not been

dead at all, and accused me of something very extreme,

of trying to take my very own life! Apparently, in my

bloodstream, they found a high volume of sleep medica-

tion. This would explain how I had to lie down, and some

of the visions I had as I lay there—snakes hissing, bodies

sliding into the ground—but I have always been happy, I

tell you.

Lucy is in fact not dead, but in the telling of her story wishes her reader or listener to believe she did die. And Lucy’s assurance that she has “always been happy” is in direct contradiction to one of her own ominous statements from earlier in the novel. When, as a child, Lucy’s young love kills himself, Lucy confesses, “I know this will shock you, for I was always so happy, your airy fairy girl of the woods, the girl who lives in, but doesn’t know, darkness: that is just how I died too in the end.”

Furthermore, at different points in the novel, both of Lucy’s sisters, obviously struggling with their own demons, visit her and say, “I’m going to tell you something.” But in both instances, as answers loom for the reader, Lucy refuses to disclose what her sisters said. In the case of Merry, Lucy tells the reader, “But I can’t tell you what she next said. Fill it in, with the worst thing you could imagine: _________________.” Whatever has occurred, wherever she exists, Lucy, in her concoction of fables, fairy tales, and stories, never comes out of the shadows to clearly resolve this buried conflict. As such, the reader is consistently left in the dark when he or she might prefer to have a bit more context to light the way.

It’s clear Bernheimer is interested in both using the surreal and fantastic nature of fairy tales to create original stories and subverting certain limiting conventions of these same fairy tales, such as the straightforward, simplistic, and moralizing endings. And in this scope, she succeeds. Below the surface of Lucy’s own story boils the collective unconscious of stories told and retold over hundreds of years, giving Bernheimer’s modern twist on these fairy tales a simultaneously alien yet comfortingly familiar feel—a not entirely unpleasant place to be lost.

In addition to Bernheimer’s weaving a complex story that favors repeated readings, as well as a close reading of Lucy’s sisters’ stories, the reader has to admire her sheer commitment to the aesthetic completeness of the novel. From the dedication to Merry and Ketzia at the beginning of the book to a number of photographs that punctuate the novel being attributed to the Gold family, Bernheimer truly tries to create an immersive world for the reader to wander through. And although at times the novel’s flights of fancy might confuse or lose the reader, the novel’s compactness and Bernheimer’s generally tight control of language, syntax, and word choice ensure the reader’s willingness to push through with interest to later illumination.

About the Reviewer

Nick DePascal currently lives in Albuquerque, NM with his wife and son, where he's working towards his MFA in Poetry at the University of New Mexico. His poetry and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in The Los Angeles Review, Sugar House Review, Rattle, Rain Taxi, Tucson Weekly, Adobe Walls, and more.