Book Review

Upon first flipping through this book, the reader’s eye is eventually—no, abruptly—brought to the photograph on page 113 of nineteen-year-old African American Michael Donald, dead and hanging by his neck in a tree. So unreal is the image—the body contorted in rigor mortis, the face strangely, unnervingly peaceful, despite the blood and dirt that covers it, despite the thirteen loops of the “classic Klan noose” that rise, taut, behind it—that the reader almost cannot agree that this is actually a human body. Then, slowly, the reader suspects that it isn’t only the unreality of the image that so unsettles the viewer, the ludicrous absence of life in still black and white, but the disturbing reality of the carnage that lead to the existence of the photograph in the first place.

Upon first flipping through this book, the reader’s eye is eventually—no, abruptly—brought to the photograph on page 113 of nineteen-year-old African American Michael Donald, dead and hanging by his neck in a tree. So unreal is the image—the body contorted in rigor mortis, the face strangely, unnervingly peaceful, despite the blood and dirt that covers it, despite the thirteen loops of the “classic Klan noose” that rise, taut, behind it—that the reader almost cannot agree that this is actually a human body. Then, slowly, the reader suspects that it isn’t only the unreality of the image that so unsettles the viewer, the ludicrous absence of life in still black and white, but the disturbing reality of the carnage that lead to the existence of the photograph in the first place.

“I could not fathom the senselessness . . . ,” says District Attorney Chris Galanos of the morning he watched Donald’s body being cut down from a tree. It was March 1981. “I remember staring at that body and being overwhelmed with a rush of emotions—the senselessness of the act. . . . ”

B. J. Hollars could not fathom the senselessness either. So he wrote a book.

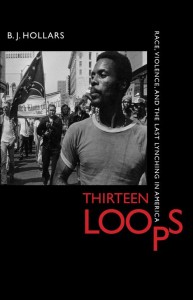

Thirteen Loops: Race, Violence, and the Last Lynching in America is a feat of investigative journalism, chronicling the horrific events that surrounded three separate—though, as Hollars aims to prove, deeply connected—murders in the state of Alabama: In 1933 Tuscaloosa, a young white woman is killed on her way to deliver a pail of flowers to her neighbors, a crime that leads to the lynching of two black men whose guilt was never established. In 1979 Birmingham, Sergeant Gene Ballard is shot and killed in his squad car when a young black man, having just robbed a bank, happens by. And in 1981 Mobile, the night the verdict in the case against Ballard’s alleged killer is announced—not guilty—Michael Donald is abducted, beaten, strangled, stabbed, and hanged by two young Klansmen who mean to teach Alabama blacks—and sympathetic whites—a lesson.

Three murders, two lynchings, a history of racial violence, and very little sense. Thankfully we have a writer like Hollars, a Tuscaloosa native, willing to brave these maddening depths, to relive his home state’s darkest nightmares, and, against all odds, combat illogic with a rational, literary consciousness. “I became invested in recounting the stories the victims could no longer tell themselves,” Hollars writes in his introduction, expressing his resistance to “sensationalism” and “hyperbole,” the stuff of the senseless acts he scrutinizes. “In matters such as these, the truth is often enough.”

This book, however, is far from the cold retelling of facts. Facts they are, and astounding facts at that, but in order to find the “truth,” or rather, the “logic” behind these crimes, Hollars must enter the story himself, if not in person (Hollars was not around, after all, to actually witness these crimes, though his physical presence is felt through conducted interviews, returns to crime scenes, the cultural inheritance of these stories, Alabama’s stories, almost mythic in their brutality), then in mind. It is this literary consciousness that makes the connections, that places, or attempts to place—rather than the successful defense of a thesis on racial violence, this is a book about the importance of the attempt itself to uncover it—a cause-effect structure across the decades, tracing certain eruptions of Southern racial violence from 1933 to their eventual results in 1981 and even, if the reader does not heed the book’s inherent warnings, to the present.

Hollars goes beyond the stats and semantics, the definitions of the words lynching and mob—“Yet how do we account for the arbitrariness of defining a mob as three? . . . Why not four or five? Why not a dozen? . . . Is the number not irrelevant when the outcome remains the same?” He presents not only cases, not only the names of the victims, “of whom there are many,” but their lives as well, and the lives of those they touched, lingering to capture the dynamic humanness of all involved, from Gene Ballard’s wife on the day of her husband’s death—“Gene always told me, if anything happened to him just to stay put and they’d send someone for me. I called the police department to see if they’d heard anything…I asked if they were sending someone for me and they said yes”—to Donald’s killer, Henry Hays, waiting out his sentence on death row. So vividly and lyrically does Hollars capture his subjects (as the following passage about Michael Donald will attest), the reader could swear Michael’s tragic ends were never met:

Though I didn’t know him, it’s how I choose to remember him; the [basketball] gripped tightly in his hands or weaving between his legs, his shoulder tucked low…

He turns, he shoots, and the ball lingers high above him, spinning, tracing an invisible path.

And Michael’s waiting now, watching, standing tiptoed as he tries to will the ball…

His eyes close, his body relaxes, and then, he inhales again.

But despite these moving passages, the irrationality of these events continues to linger, and Hollars continues to combat them with indefatigable irony. He juxtaposes the many lines of narrative that run through these crimes, like the editor of a documentary, assembling strips of story piecemeal, returning to the same scenes again and again from various, oftentimes contradictory angles of the camera: “It seems somehow inconceivable that Michael Donald was lynched the same week REO Speedwagon’s “Keep On Loving You” was at the top of the pop charts… Acid-washed jeans and parachute pants and a lynching in Mobile.”

As baffling as the anachronistic events themselves is Hollars’s eye for the ironic detail: Birmingham News reporting on the results of the Iron Bowl two days prior to Sergeant Ballard’s funeral, “Alabama giveth, Alabama taketh away”; the surprising “similarities between the actual events of Michael Donald’s night and the partially fabricated events of Henry Hays’s,” the only difference being that “one was black, one was white, and one returned home in the morning”; the NAACP Legal Defense Fund working to protect Hays from the electric chair, a representative saying, “We work against the death penalty no matter who it’s directed against”; the autopsy results noting that “while his actions spoke to the contrary…Hays’s heart weighed ten grams more than Michael Donald’s.” Through his irony, Hollars seeks out an alternative form of logic, hiccups in our grand narratives that betray that inscrutable fabric of our lives, the stagehands in the wings, the boom in the shot, never ceasing to find poignancy in the irony, if not, simply, beauty:

While the former Klan headquarters resides on one side of Lake Tuscaloosa, Prewitt Cemetery—one of the oldest slave cemeteries in the nation—sits on the other. It’s an odd contradiction—one location for perpetuating hate and one for preserving love. Yet regardless of purpose, both locations are picturesque, hidden among the trees on quiet roads, just short walks from the water.

But most poignant of all is the eventual, admitted failure of the writer to effectively, as Hollars terms it, unravel the rope. “How can we ever accurately judge the deeds of the past?” he writes in an affecting display of subjugation. “So far removed from the events themselves, we are often forced to rely on newspaper reports and history books. And yet the accuracy of any source is suspect—no one motiveless—leaving us to pull at truths from the tangles of history, hoping that, eventually, we learn to pull the right threads.”

In the end, the message of the book is one of redemption: a world of loose constructs, of savagery and pain, of black and white, of being “in the wrong place at the wrong time,” we must strive, as humans, as storytellers, against all odds, to combat illogic, to unravel the many ropes of injustice and strange coincidence. That is the beauty of Hollars’s book. When faced with no real answers, or rather, when the answers are many and contradictory, it is the attempt itself that defines history.

About the Reviewer

Nicholas Maistros received his MFA in fiction from Colorado State University. His work has appeared in Nimrod and Bellingham Review. He currently teaches at CSU and lives in Fort Collins.