Book Review

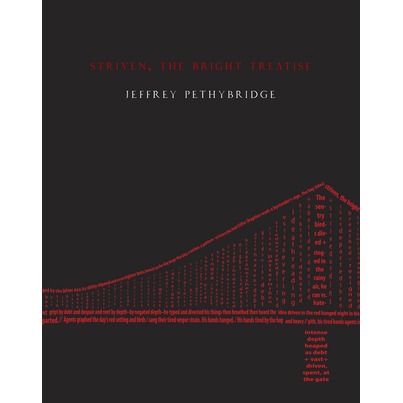

Jeffrey Pethybridge’s stunning first collection, Striven, The Bright Treatise, offers readers a graceful synthesis of art and ethics. Described by Aaron McCullough as a “study in grief,” the book uses autobiographical material as a point of entry to a thought-provoking discussion of suicide as a social, philosophical, and ultimately political problem. Although Pethybridge draws from numerous points of view—which range from Emile Durkheim, Dante Alighieri, and Shakespeare to John Cage—his use of invented forms lends a beautiful sense of unity to the collection. Pethybridge invokes formal constraints to suggest the myriad ways in which one’s fate is inscribed by culture, biology, and political systems, allowing style and technique to illuminate the pressing theoretical concerns that motivate his work.

Jeffrey Pethybridge’s stunning first collection, Striven, The Bright Treatise, offers readers a graceful synthesis of art and ethics. Described by Aaron McCullough as a “study in grief,” the book uses autobiographical material as a point of entry to a thought-provoking discussion of suicide as a social, philosophical, and ultimately political problem. Although Pethybridge draws from numerous points of view—which range from Emile Durkheim, Dante Alighieri, and Shakespeare to John Cage—his use of invented forms lends a beautiful sense of unity to the collection. Pethybridge invokes formal constraints to suggest the myriad ways in which one’s fate is inscribed by culture, biology, and political systems, allowing style and technique to illuminate the pressing theoretical concerns that motivate his work.

His finely-crafted sequence “The Book of Lamps, being a psalm book” exemplifies these ideas. Presented as a 128 line poem, with one line for each pole on the Golden Gate Bridge, the piece uses formal constraint to mirror the ways in which individuals suffering from emotional problems are often silenced, ostracized, and alienated within mainstream society. In much the same way as the poem is coerced into its chosen form, with its seemingly chance enjambments and fragmented syntactic units, the text itself conveys the sense of estrangement experienced by many who contemplate suicide. With that in mind, each formal decision is carefully considered, well-executed, and purposefully complicates the text itself, adding to the possibilities for interpretation. Consider this passage:

…Palms open and upturned—

good little supplicants, what is their (secret) prayer, what is open to praise? candor?—the pure

fact of the four irrevocable seconds?—the right note to elicit briny air, of the thick beach

chill along the skin at dusk—palms pressed against the limit—the nouns to summon it:

This passage suggests that mainstream society privileges conformity. As a result, those suffering from emotional problems risk judgment by their peers, and more often than not, attempt to conceal what might be considered inappropriate affect. As Pethybridge narrates the “secret prayers” and innermost thoughts of these individuals, the form of the poem suggests the impossibility of reconciling this emotional turmoil with the demands of culture. In much the same way that the poem appears in fragments, frequently ruptured by dashes and caesuras, Pethybridge implies the impossibility of integrating this negative affect into the pristine master narratives that are imposed upon individuals in contemporary society.

Pethybridge’s use of white space, caesura, and typography also proves noteworthy as the book unfolds. Frequently using these literary devices to gesture toward the ineffable, the poet suggests the myriad ways in which we are limited by language itself. For Pethybridge, the society we inhabit lacks the resources to appropriately deal with negative affect, mostly due to our lack of ability to adequately express, and subsequently understand and analyze, feelings of grief, despair, and hopelessness. With that in mind, Pethybridge incorporates black pages throughout the book, referred to as “mourning pages,” and uses white space in innovative and visually striking ways. These moments when the poet turns away from language are among the most powerful in the collection. In “The Sad Tally, being a vocabulary, map, and ode,” Pethybridge writes:

Striven in the debt-age, its red hanged air, its graphs and sentrybirds [the lamps will come on soon the lamps will come on soon]”I hate this ‘I,’ this tired agent” he said—striven, the tired age entire, its sign

The fact that this passage is written in the shape of a bridge, in many ways an emblem for modernity and its discontents, renders it all the more poignant. For Pethybridge, suicide would not be such a pressing ethical problem were it not for the things we consider as markers of social progress: credit cards, consumer culture, and even language as we know it. With that in mind, the poet’s turn away from language in pieces like this one constitutes an act of resistance, a search for alternative modes of thinking, writing, and representing experience that would ideally reside outside of a consumerist framework. Striven, The Bright Treatise is filled with beautifully crafted poems like this one, in which technical choices illuminate and complicate the text itself. In short, Pethybridge’s first book is a truly remarkable debut.

About the Reviewer

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of fifteen books, which include Melancholia (An Essay)(Ravenna Press, 2012), Petrarchan (BlazeVOX Books, 2013), and a forthcoming hybrid genre collection called Fortress (Sundress Publications, 2014). Her awards include fellowships from Yaddo, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and the Hawthornden Castle International Retreat for Writers, as well as grants from the Kittredge Fund and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is currently working toward a Ph.D. in Poetics at S.U.N.Y.-Buffalo.