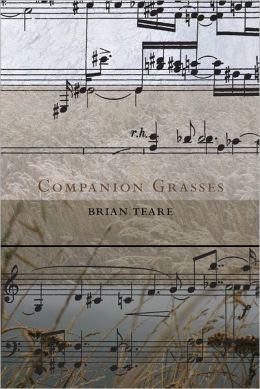

Book Review

In Companion Grasses, Brian Teare embodies the definition of poet as daydreamed by Thoreau while “Walking,” the poet who would transplant words “to his page with earth adhering to their roots…who could impress the winds and streams into his service, to speak for him.” Teare sustains a philosophical-linguistic dance-conversation with Thoreau, Dickinson, Emerson, and others contemporary and ancestral, literary and familial; he produces original and authentic art as he adheres to origins. Consider the delight in “Little Errand”:

I gather the rain

in both noun

& verb. The way

the river banks

its flood, floods

its banks, quiver’s

grammar I carry

The book’s arrangement into three distinct sections feels intentional and intuitive, while remaining collaborative with content. The poems in part one are particularly resonant of a naturalist’s guide, and have the effect of illuminating without mediating—the best guide helps us see with our own eyes. As the poet surveys, he impresses rural and urban landscape into his service; they help him speak, or he helps them. Physical landscape shapes poetic form—text on open field pages echoes edges and ocean, rivulets and hillocks and ledges. Land or ocean or idea offers, and Teare meets it in “White Graphite / (Limantour Beach)”:

the spit’s edge open

to ocean goes pure

contour : absence

of light, self’s how

a tern’s clutch nests

in next to nothing :

beach without moon

mere rumor, blur’s

texture a scumble

scoured of color :

…

matter a mere shift

in limits, even skin’s

a trick of the liminal :

This opening poem holds much of the book’s explorations in microcosm: precise arrangement of words and lines; form reflecting content (here, spare language sketches images and concepts of edge and space); a glimpse of the elegiac to come; language as extension of thought and/or thought as extension of sound; and an introduction to one of the theoretical threads pursued across the book (the relationship between matter and spirit).

A summer walk offers, as in “Quakinggrass /(Briza Maxima),” and Teare braids multiple perspectives, “not collage exactly,” into a poem that combines landscape with language and biology: “Gnats hovered above dirt /path between chaparral /(pretty word—Spanish—‘evergreen oak’—”. After isolating personal and ecological threads, Teare entwines them with theory as the speaker walks alongside an unnamed “he” whose “storied thigh/scarred just so… & tilted toward me”: “I followed him— / no one had said ‘love’ yet— / high bluff cliffing the Pacific…(‘a detail overwhelms // Entirety,’ writes Barthes)—”. The poem weds etymology and translation with attraction, weds landscape with theory, as varied in its spatial arrangements and mechanics as in its content, and ends/arrives at:

Little grammar of attraction—

Inflorescence—

(What is “lyric”)—

The book fell open on its broken spine

(florere, “to flower”)—

“It’s quakinggrass,” I said—

When Emily Dickinson was down, her lexicon was her companion. Here, too, where phenomena’s best expression comes in terms of absence—“not collage exactly,” not love “yet”—and suggests larger absences—it is language that provides structure and shelter. The speaker wants “to get / closer to where material / touches language”, wants “two grammars to / marry the mutable to fundament.”

In part two, the center of Companion Grasses, rests Teare’s “Transcendental Grammar Crown”: a gem-studded crown that opens with five epigraphs, one each by Emily Dickinson, Margaret Fuller, Charles Ives, Emerson, and Thoreau—invocations for the carefully shaped musing that follows. The sequence, a laurel of fifteen poems, fourteen lines each, weaves signature insights in a mode both critically engaging and laudatory, perhaps as consolation for other facts, or death, or the fact of death. The sequence is part prayerful garland, part homage, part smart literary love note. The poems are not mimetic of the work by those invoked in the epigraphs—rather more ekphrastic in how they speak out across time and space and genre to connect with ideas, more synchronized as in breathing with. It’s a pleasure to witness Teare give these ideas additional faces and forms, as in the beginning of the paean “What’s / (—)” to Dickinson and her signature dash and slant rhyme:

as saint

is slant

to pain

storm norm numb null

thorn pressed to thumb

The poems in this section are further woven together by echo and repetition of the last line of each poem to the first line of next, so that the poem that contains strands of Emerson’s “Oversoul,” and ends with the words “sweeter than seeing,” is followed by a poem entitled “Vision Is Question”; and the last lines of the last poem, “…the leap from matter / to a transcendental grammar,” harken back to the first poem, “Leap From Matter.” In the end, it seems it’s the Thoreauvian more than the Emersonian brand of transcendentalism held aloft. The poems’ power to convey the spiritual comes from forms in the natural world, and love of those physical forms, despite or because they are ephemeral, as in “Star Thistle /(Centaurea solstitialis),” dedicated to Reginald Shepherd (April 10, 1963-September 10, 2008):

the thistle is not metaphor

& extends into the future

as far as I can see, easily filling the field I love :

…

& the wild deer in us were released at last

at dusk to disappear into the stand of manzanita far across the field I love :

The book contains a weave of praise, consolation, critical inquiry, and lamentation. The critical inquiry is not found exclusively in the more essayistic poems, nor is the mourning limited to the book’s two final poems, one dedicated to the poet’s father, one to poet Reginald Shepherd. It is a distinct feature of this book that it impresses into service both logic and passion, and that it can sustain a nerdy delight in physical artifacts alongside metaphysical meditations.

Thoreau, in his relative solitude at Walden, which is to say his self and spiritual exploration, speaks of the impossibility of loneliness (and perhaps the impossibility of endless mourning) when he writes that in his solitude “Every little pine needle expanded…with sympathy and befriended me.” A similar suggestion and inherent argument is made in Brian Teare’s Companion Grasses, which renews intimacy with language, fact, landscape, literature, and everyday feeling—such rich company.

About the Reviewer

Jacqueline Lyons is the author of the poetry collection The Way They Say Yes Here (Hanging Loose Press, 2004) and the chapbook Lost Colony (Dancing Girl Press, 2009). She teaches creative writing at California Lutheran University.