Book Review

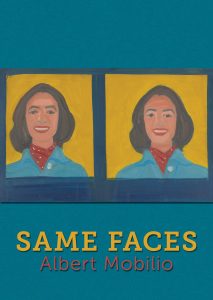

In Albert Mobilio’s poetry collection Same Faces, readers encounter a tour de force of personal, artistic, and social commentary. Immediately, readers will notice the focus on faces: an image and construct that permeates the collection both literally and figuratively, as the narrator poses not only images of human faces, but images of emotional face(t)s and “faces” formed by landscapes and “headscapes.” Nonetheless, readers will also notice something else—careful shadowing appears throughout the collection in gracefully posed questions such as: “What’s the story they tell about strangers at doors?” balancing the darkness of statements like, “Dreary occasions spent posing: / however strong / we set our chins the photos lacked plot.” In its entirety, Mobilio’s collection summons images of paintings like Caravaggio’s Narcissus because of their tenebrism—the artistic concept of dramatic illumination created by violently contrasting light and dark and utilizing darkness as a dominant feature. The intricate structural and verbal tenebrism combines with the collection’s triptych structure and forces readers to consider the collection not only as a whole, but in the way its smaller sections act as autonomous frames within the collection. Mobilio’s Same Faces, like Caravaggio’s Narcissus, consists of three frames. The first frame one might notice in Narcissus is the black, detail-obscuring pool into which Narcissus stares, his features somewhat unrecognizable. The first section of Same Faces––untitled with poems whose structures waft between couplets and tercets and quatrains––is like the pool into which Narcissus stares. With its powerful opening poem, “Triumph of Poverty,” the narrator creates a depressing scene:

In Albert Mobilio’s poetry collection Same Faces, readers encounter a tour de force of personal, artistic, and social commentary. Immediately, readers will notice the focus on faces: an image and construct that permeates the collection both literally and figuratively, as the narrator poses not only images of human faces, but images of emotional face(t)s and “faces” formed by landscapes and “headscapes.” Nonetheless, readers will also notice something else—careful shadowing appears throughout the collection in gracefully posed questions such as: “What’s the story they tell about strangers at doors?” balancing the darkness of statements like, “Dreary occasions spent posing: / however strong / we set our chins the photos lacked plot.” In its entirety, Mobilio’s collection summons images of paintings like Caravaggio’s Narcissus because of their tenebrism—the artistic concept of dramatic illumination created by violently contrasting light and dark and utilizing darkness as a dominant feature. The intricate structural and verbal tenebrism combines with the collection’s triptych structure and forces readers to consider the collection not only as a whole, but in the way its smaller sections act as autonomous frames within the collection. Mobilio’s Same Faces, like Caravaggio’s Narcissus, consists of three frames. The first frame one might notice in Narcissus is the black, detail-obscuring pool into which Narcissus stares, his features somewhat unrecognizable. The first section of Same Faces––untitled with poems whose structures waft between couplets and tercets and quatrains––is like the pool into which Narcissus stares. With its powerful opening poem, “Triumph of Poverty,” the narrator creates a depressing scene:

What graph demonstrates what we’re improving?

There’s a newer model in the catalog.

We drive, carry, then drive further.

Sky crowded with gray—metal rubbed in soot.

The decorations are sagging, the dance is over.

Longing on faces, faces hung like freight.;

Gaze entertained by an incessant to-and-fro.

According to experts, heredity is our factor.

A nihilistic obscuring occurs, beating into readers’ psyches despair and hopelessness, and like the negative image of Narcissus in the pool, shadows cover both the narrator’s and the collection’s “face”: “Zero times zero performs a scurrying sound.” As the first section’s “face” continues to open and express, poems such as “An Implication” become like the shoreline onto which Narcissus balances himself in Caravaggio’s painting, that point where subtle light bleeds into the darkness and causes readers and viewers to shift their eyes to the midpoint and pause. “An Implication” continues with more despair, but this time the despair blends with John Entwistle-like humor that both shocks and delights readers: “Look what happened to my broken toaster. No one fathoms the / distress I endured when it died.” What is most powerful about this shift is that the narrator now focuses not on themself and the duress and distress they bear. Instead, the narrator focuses on an inanimate object, their relationship to it, and how its “death” causes anxiety, emotion: “I don’t have the connective tissue that enables me to wear my / own face without distraction; hence, I am a ringer for myself.” The reader then leaves this section with the help of the poem “Wanderers,” and the light, like those objects depicted at the midpoint of Narcissus, remains dim but growing brighter: “The treatments you get may not explain the problem / but they restore your grasp of its lexicon.”

The second section of the collection, titled “The Same Faces You Can’t Believe In,” is like the second frame of Narcissus, where viewers see his face more fully. Light casting from the frame’s left corner reveals flesh tones, a white blouse, light brown hair, smooth skin. In Same Faces, the “casting” of “light” occurs via the act of erasure. Readers encounter full narrative poems like “This dancer is out,” a seemingly self-deprecating work declaring “This dancer is out of step with that one whenever / the mood makes you wish you.” When readers turn the page, just like when the viewers of Narcissus shift their eyes, “light” has illuminated the work’s smallest details. In “this dancer,” “This dancer is out” is reduced to its smallest parts: “step whenever / the mood makes / your mental / crumbs / come home.” The words extracted from the larger narrative become like the careful folds and threads visible in Narcissus’s blouse, the small spot at his collarbone revealed for all to see. The philosophical poem, “By the time summer arrived,” is just as powerful in its embrace of this technique as it depicts a human’s recognition of his painful place in existence:

By the time summer arrived he knew he was a long

digression in everyone else’s argument even

though he drank a beer quickly to chase

off the smell of burned up worlds he should have

set the toaster on medium but outtalked is why

he found himself stuck in what old doc grady

dubbed a painful marital situation.

When the “light” filters onto this poem and its smallest details become visible in the brightness, what emerges is “the time,” an imagistic stream that, with its observances of “burned worlds” and “this man / free of tarnish” and its command to “lie inside memory” waxes reminiscent of German synthpop band Wolfsheim’s psychologically thrilling song “Upstairs.”

Small Faces closes with a resolved, meticulous third section titled “Guide for the Discouraged.” Reading this section is like stepping back, looking at, and studying Narcissus in its entirety. The reader notices how the collection’s three parts, despite their autonomy, need one another, rely on one another. Here, the collection continues its intellectual and emotional dramas: materialism’s choke hold on the individual, the symbolism nature provides to a hopeless existence, the struggle of the individual against a society hellbent on killing wanderlust and identity, the demise of intimate relationships one believes will last an eternity—because that’s the way fairytales, forever-afters, and societal expectations portray them. Readers return to the other two sections with those individual calamities, oppressions, and shortcomings in mind in order to fully understand the entire collection. In “Guide for the Discouraged,” the narrator pulls out all the stops: “I’m always taking the test—the cake / I have or the cake people recall.” These opening lines—with their subtle allusion to a historical misquotation associated with Marie Antoinette—like Narcissus’s continued staring into the pool at his own reflection, establish selfhood and defiance, a will that no outside force can counter. The speaker of the poem continues the contemplation of self as it relates to, and fits into, the surrounding details by posing the self as the smallest part of an infinite whole. Sciences and the universe are invoked: “There’s no mystery. Astronomy / makes us lazy by fixing our sight / on the exit light.” The narrator’s despair and nihilism established in the first section thus returns and continues—again drenched with black humor—acting as the invisible lines between literal and metaphorical darkness and light: “If grief is a cunning guest we should / hide the towels.” The collection ends rhetorically, with images of “A wretched stranger” who fell “prostrate at her door.” The narrator experiences a self-reckoning: “Me in action—a marionette whose flailing / limbs mock my ardent ascent.” The reader receives a challenging, prophetic warning:

You look and look but the mirror

remains unchanged. The mouth

is ruined by silence, the gaze will not

relinquish its obdurate pity.

Readers bring to this collection what viewers of Caravaggio’s Narcissus bring to the painting: the stark awareness of shifting light and encroaching darkness, the observance of the careful balance of the fine and the dense which shape and form and mold not only the individual poems, but also the sections, and the collection in its entirety. The twist of the shortest word in a line of the longest poem acts as a flicker of light brightening the most minute detail in the frame, and the power of this collection lies in those word-twists, the emotional turns that act like the curl of an upper lip on a face ready to express the slightest bit of emotion.

About the Reviewer

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian-American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, is the recipient of a July 2020 Writing Residency at Gullkistan, Creative Center for the Arts in Iceland, and is a Tupelo Press June 2020 30 for 30 featured poet. Her poetry collection Triskaidekaphobia is forthcoming from the UK press Black Spring Eyewear Group in 2022.