Book Review

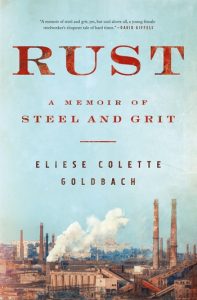

In Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit, Eliese Colette Goldbach reflects on her childhood as the second daughter in a Polish-Catholic family and her three years as a steelworker. As a little girl in Cleveland, she could often see the rust-colored buildings of the city’s steel plant in the distance when she rode through town with her father. Goldbach never imagined her identity would become Utility Worker number 6691, or that Trump would become President: “I wasn’t supposed to be a steelworker. I wasn’t supposed to spend my nights looking up at the bright lights on the blast furnace . . . I attended an all-girls Catholic high school. I ran track. I played Beth in a school rendition of Little Women, and I was valedictorian of my graduating class.” Goldbach’s conservative childhood was mine, and even if it’s not yours, it provides a lesson as to why large parts of the United States vote Republican and suggests how we might approach narrowing a widening chasm of philosophical differences.

Other critics have compared Goldbach’s Rust to J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy and Tara Westover’s Educated. It also shares similarities with Darnell Moore’s No Ashes in the Fire because it’s an insider’s story. There are elements of all three, but Goldbach’s voice and story are uniquely hers. Rust tells a story so personal and experiential that it reminds us that only those on the inside can criticize, empathize, and inevitably distill and postulate about what life’s really like in Cleveland—a city nicknamed “the Mistake on the Lake.”

Goldbach completed her MFA but never received her diploma when she failed to fill out a form. This small act is symbolic of a series of fragmented failures. She’s crippled by student debt, is in a dysfunctional relationship, and spends her days painting houses. Buried in her malaise is a traumatic event that her college swept under the rug and minimized.

When painting a former college classmate’s house, Goldbach learns her friend is working at the mill. She tells him she’s not cut out to be a steelworker until he shows her his paycheck. We learn that “hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people vie for a few open spots.” Like Goldbach, “they want the American dream, or what’s left of it.” Even though the “air still stank of rotten eggs,” she explains that “sulfur was the smell of shifting fortune.” When she takes the reader inside the mill, she’s not just providing access to the inner-workings of a blue-collar worker’s life. She is reflecting back on what brought her there in the first place.

Goldbach has a gift for writing visually arresting scenes. Reading that the dust settles on everything—on walls and fingers, on forklifts and lunches, we imagine the air she breathes and fear for what must have taken residence in her lungs. We weather the six-month trial period where orange hats must prove themselves worthy of a yellow hat and admittance into a life of security as a union worker. Goldbach outlines the stakes when an old-timer tells her about another worker’s ghastly accident: “Imagine it, the old-timer said to me. The weight of that steel. It just split her in half.” The tension rides high in the mill where a steel coil can crush a worker at any moment, or a single drop of water can explode a vat of iron.

How do you reconcile making money from an industrial complex that puts workers at risk? How do you criticize what saves you? The answer is: you don’t. You look below the surface to tell the stories of those who can’t and share one of life’s greatest lessons: what it means to be a small part of something big.

Goldbach’s education at the mill becomes her salvation and her political awakening. We witness her challenging her parents and millworker’s politics at the dinner table in what has become commonplace at dinner tables all across the country. But at a time when the nation is divided geographically, politically, and demographically, Rust feels like a salve. Goldbach could have easily dipped into a diatribe about sexist, patriarchal, Trumpian back-slappers. Instead, she looks through an empathetic lens to provide insight into how and why most of her co-workers and family believe Trump is their salvation as she notes: “We were Republicans because God wanted us to be Republicans. Satan had corrupted the Democrats by tricking them into the sins of abortion, homosexuality, and, worst of all, feminism.”

Rust isn’t just a book about blue-collar workers or quaffed aspirations. It’s a personal narrative about what it’s like to keep a flame alive. The vivid orange flame shooting above the Cleveland steel mill comes to represent the inferiorities of the workers as much as the surrounding inhabitants and their collective histories, tenacity, and resilience. “In a Rust Belt town, that flame isn’t just a harbinger of weird smells and pollution. . . . The flame is very much a part of our history and our identity. It’s a steady reminder that some things can stand the test of time, even in a world where nothing is built to last.”

A lot is going on in this memoir—sexual assault, restrictive religion, politics, life as a steel mill worker, and mental illness—revealing the utter complexities of a challenging life. I can see how some might suggest that there are too many themes in this memoir. But who are we to relegate simplicity, when at its heart, is an honest account of a complex and challenging life and its redemptive narrative of hope and resilience?

What struck me as the most poignant lesson in Rust, is that when the stakes were life or death, liberals and conservatives forged a unified front—as solid as the steel they produced. Goldbach never gives up hope or is denied her dream in the end. And if she can bridge the divide of politics to love the people she came from while rejecting their ideals, perhaps there is hope for all of us?

About the Reviewer

LaVonne Elaine Roberts is an American short story writer, essayist, and memoirist. She is LIT Magazine’s Live with LIT Editor, Cagibi Lit’s Interviews Editor, and the 2020 Diversity Fellow for Drizzle Review. Her essays, short stories, and poetry have been published widely, including in Our Stories, Too: Personal Narratives by Women, WordFest Anthology 2019, The Blue Mountain Review, LIT Magazine, The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, Litro, among other publications. She is the founder of WRITE ON!, where she leads writing workshops and provides literature for marginalized voices. She resides in New York City, where she is completing an MFA at The New School and a memoir called Life On My Own Terms. Her work at Drizzle will include curation of a special issue on ageism in literature, due out in summer of 2020.