Book Review

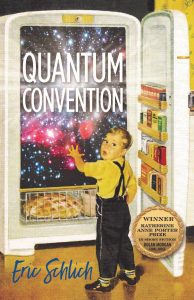

The stories in Quantum Convention, the 2018 winner of the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction, have a playfulness that one normally associates with light reading. Indeed, many of the stories draw the reader in with humor and a measure of absurdity. But there is nothing inconsequential about the subject matter underlying each of the stories. Instead, the lightheartedness of the stories serves to prime the reader to enter into uncomfortable explorations of human existence. As such, each story in Quantum Convention contains both the proverbial spoonful of sugar and its companion medicine, all in one dose.

In the title story, “Quantum Convention,” the protagonist attends a convention in which he can meet the other versions of himself that exist in parallel possibilities of existence. Of course, the experience is not what he expects, and the specific versions of himself that he meets—which he gives nicknames like “Aftershave Me,” “Prom Date Me,” “Fashion Disaster Me,” and “Mullet Me”—are neither inspirational nor affirming. Their conversations are, however, hilarious, as they explore all the consequences of choices, big and small, on a life. But the story does not stop there. It is when the protagonist runs into his wife that we understand why he has been looking for answers from himself and the universe—and how very doomed this pursuit is. The story suddenly changes from a humorous imagining of a concept of self that has long tempted the introspective to a cautionary tale about relying on an immersion in self-examination to avoid figuring out how to live. The story is lighthearted while it also engages with a universal truth of human existence when faced with unanswerable questions about identity.

Similarly, the story “Lucidity” at the outset reads like a parody of self-help and other wellness initiatives. It tells the story of man who looks to a dream-improvement group—complete with journaling, a guru and mantras—to improve his sleep story lines. This seems like a mismatch because his life situation—his plainspoken friends, his job involving physical labor, his probation officer, and other hinted circumstances—make him seem too grounded to want what sounds like complete quackery. Only in tiny bits and pieces—almost in the manner in which facts arrive in dreams—does the reader come to understand the dark secret hidden in his past: his desire for the ludicrous dream improvement is to combat the nightmarish quality of the background narrative to his waking and sleeping. What’s most striking is that this desire for relief from reality, particularly the escape from reality in one’s own mind, is terrifyingly relatable to the reader.

A natural continuation of the same kind of tale, “Merlin Lives Next Door” is a matter-of-fact account of a magical being who stalks the ordinary, if compulsive, narrator through time. It would be compelling if only because it deserves a place within the recent coterie of books and stories dealing with magic as an incidental or prosaic background—what one might think of as the post-Harry-Potter genre. But as part of this collection, it resonates beyond mere entertainment as it explores how little humans notice about their own lives and choices until they fall under someone else’s scrutiny. In the story, the narrator’s neighbor, Merlin, has magic, but not of a useful or miraculous sort. The magic merely alienates neighbors and wreaks havoc on the dishware that he constantly breaks when he zaps out of time at inconvenient moments. Merl, as he prefers to be called, is ultimately neither likable nor insightful. His only value seems to be as a mirror to the protagonist who is otherwise content to live his life by a rigid regimen without self-reflection or critique while his life slips away. Only when he realizes his stalker has been present at every key moment in his life, does he reflect on his choices and considers living differently.

Not only does Schlich have fun with content, but he also beguiles the reader with playfulness in form. The main story line of “The Keener,” in which a silent orphan is drafted into a troupe of professional funeral mourners, alternates with versions of fairy tales about a banshee told by several characters. While this is a fairly common story-within-a-story style, what is more unusual is that in the telling of the banshee stories, the characters (or circumstances) make it clear that their stories are not real but have been altered to fit their purposes. Thus, the very acts of storytelling cast doubt on the veracity of narrative. Readers are pushed to laugh at themselves for trying to trust any story for meaning. In “The Keener,” Schlich makes certain that the barrier between story and truth is repeatedly blurred.

Meanwhile, “Not Nobody, Not Nohow” seems different from others in the collection because it has a historical feel and contains no overtly fantastic elements. Upon closer scrutiny, however, the reader can see this story also plays with form. The story tells a seemingly based-on-real-life account of the actress, Margaret Hamilton, who played the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz opposite Judy Garland’s Dorothy. While this account of a pivotal moment in American moviemaking and the makings of modern celebrities is absorbing enough, Schlich again intersperses this storyline with another: the bittersweet account of a six-year-old boy who spends a summer playing at being Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz only to face his classmates’ mockery upon his return to school in September. Both storylines are technically free of fanciful or unrealistic elements, however, because each one focuses on a transformation— one transformation into a character for the movie camera and the other away from a character to fit society’s expectations—there is, in the end, a similar kind of magic that makes each protagonist irrevocably overplayed with the identity of a fictional character. This alchemy and the way the two storylines echo and undermine each other are thus a perfect amplification and continuation of the qualities of the other stories in the collection.

Quantum Convention is a collection that deserves to be read alongside the work of writers such as Etgar Keret or Aimee Bender, who use the fantastic and even farcical to illuminate the universal and ordinary. Like their works, this collection bends traditional storytelling forms to perform a story, and while the stories’ premises seem almost laughable, in their execution, Schlich makes them exquisitely beautiful and painful.

About the Reviewer

Amanda Moger Rettig is a writer living outside of Boston with her husband and three children.