Book Review

“There is a painting by Paul Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at. His eyes are wide, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees a single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”

“There is a painting by Paul Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at. His eyes are wide, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees a single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”

—from Walter Benjamin’s 1940 work, “On the Concept of History,” Gesammelte Schriften I, 691–704. SuhrkampVerlag. Frankfurt am Main, 1974. Translation: Harry Zohn, from Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. 4: 1938–1940 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.)

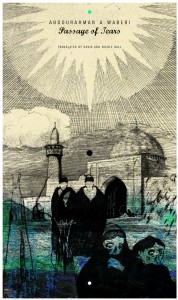

Passage of Tears by Abdourahman A. Waberi, translated by David and Nicole Ball, is as much an invocation of Walter Benjamin as it is a palpable illustration of life in Djibouti. In supple flowing prose, Waberi layers image upon image of life in that arid, rocky land where the Arabian and Red Sea meet in the Gulf of Tadjoura. Narrated in journal entries and letters penned by three separate people, the novel alternates between seemingly disparate perspectives, as if the reader were sifting through the private papers of strangers. Waberi’s central character, Djibril, now living in Montreal and working for an American economic intelligence firm whose details and objectives remain elusive throughout the novel, reluctantly returns to his native Djibouti on business. As he chronicles his activities in a series of journals, his attention is drawn ever more towards his childhood and the medley of endearing and repulsive memories so common to homecomings. But this is no ordinary homecoming and Djibouti is no ordinary land. Strategically positioned at the narrowest point between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (called the Gates of Tears), its history of French colonialism and penal colonies have displaced and marginalized Djibril’s poor and nomadic people.

Waberi alternates between the poignant images of Djibril’s childhood, such as this memory of his father:

I saw my father, walking along the mosque that goes down to the biggest square in the city. And I felt ashamed of that man, ashamed of his crab-like steps and jerky walk. Of his poverty, too. He was on foot, whereas I would have liked to see him at the wheel of a Peugeot—even a beat-up Peugeot. He was bringing back a box-spring mattress that we didn’t have at home. He was carrying it on his head, probably to save the price of a collective taxi.

And threatening letters Djibril receives from an imprisoned radical Muslim whose network is tracking Djibril’s every move. The letters are written on scraps of paper that include previous passages from an unknown author about the exiled writer Walter Benjamin. At first, Djibril doesn’t seem bothered by these letters imploring him to return to his faith in Islam or suffer death. Instead he ponders the absence of his twin brother, Djamal, the lost tenderness of his grandfather Assod, his mother’s rejection, and the unexpected childhood friend he found in a French Jew named David. The mystery of David plays a central role in both displacing Djibril’s twin from his affection and setting him on a nomadic path of his own. He has never reconciled David’s disappearance, one as sudden as his arrival, and it plays a part in his abandoning Djibouti and striking out for Paris where he met his wife, and then later on to Quebec.

The long passages within the letters that detail Walter Benjamin’s life, however, ultimately affect both men. The Muslim questions his faith, while Djibril finds a measure of understanding about his lost friend David, even as he awakens to the present danger of the Muslim’s threats.

Waberi’s novel takes a linear trajectory in its events, reading at times like a spy novel, yet the story is anything but straightforward. Readers seeking plot will find frustratingly little of that, but those willing to marinate in his imagery will reap a rich awareness of Djibouti and its struggles. Waberi provides ample clues about how to read this work, as in this passage to Benjamin, which could easily be to the author himself:

. . . more than anything, you love pasting pieces together when you tell stories, Ben. Piling stories on top of each other like the palimpsests of medieval times. Organization and classification are tempting but they do not suit your stories. You will leave traces in people’s memories.

Ultimately Passage of Tears is a story about rejection, estrangement, and exile. Waberi delivers a satisfying end that readers will consider many more times after the pages are tucked into the bookcase. Set at a strategic geographic crossroads, the novel brings together the primary branches of Abrahamic tradition in their modern and ongoing struggle for dominance and restoration. As Benjamin describes the Angelus Novus—Angel of History in Paul Klee’s painting, which Waberi quotes—Djibouti sits in the center of a region that dreams of awakening the dead and making the smashed whole again, but the storm still blows, driving it into the future. And the pile of wreckage grows toward the sky.

About the Reviewer

Heather Sharfeddin is the author of four novels. Her work has earned starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews and Library Journal, has been honored with an Erick Hoffer award and at the New York and San Francisco Book Festivals, as well as the Pacific Northwest Book Sellers Association. Her first novel, Blackbelly, was named one of the top five novels of 2005 by the Portsmouth Herald. She lives in Oregon’s wine country. She holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is working on her PhD in Creative Writing.