Book Review

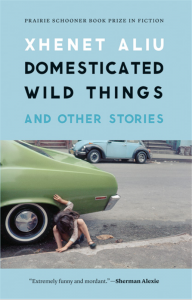

I grew up in Connecticut. More often than not, when I mention this to new acquaintances there’s a presumption that my childhood consisted of languid days on the golf course and tennis matches at the local country club—a presumption that the word “Connecticut” is shorthand for rich and privileged. When I see that knowing look in my new friend’s eye, I usually follow up by saying I was raised in Connecticut-Connecticut, not New York-Connecticut. This distinction may be lost on my listener, but certainly would not be on anyone living in Connecticut’s many small towns and struggling cities, and certainly not on Xhenet Aliu. Aliu’s first collection of stories, Domesticated Wild Things, winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, vividly captures the longing, striving and eternal disappointment in one of Connecticut’s downtrodden cities, without a golf course in sight.

I grew up in Connecticut. More often than not, when I mention this to new acquaintances there’s a presumption that my childhood consisted of languid days on the golf course and tennis matches at the local country club—a presumption that the word “Connecticut” is shorthand for rich and privileged. When I see that knowing look in my new friend’s eye, I usually follow up by saying I was raised in Connecticut-Connecticut, not New York-Connecticut. This distinction may be lost on my listener, but certainly would not be on anyone living in Connecticut’s many small towns and struggling cities, and certainly not on Xhenet Aliu. Aliu’s first collection of stories, Domesticated Wild Things, winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, vividly captures the longing, striving and eternal disappointment in one of Connecticut’s downtrodden cities, without a golf course in sight.

Aliu knows her setting: the decrepit houses, the cars jacked up on cinder blocks, the smoking section at the Greek diner, the YMCA pool. And she knows the people who call it home. Her characters spring from the page in all their crass completeness. Here is a B-grade pro-wrestler who won’t quite give up on the big time; a desperate single mom looking for her big break in real-estate foreclosures; a teenager who escapes her own family’s dysfunction only to land in another’s equally treacherous waters. Their endless failures may not surprise us, but their eternal optimism might. It’s easy to live the American dream when hard work translates into a step up the ladder of well-being, financial or otherwise, but would you feel quite so sanguine when every door you opened led to a worse reality? We mourn for Aliu’s characters’ inevitable losses, but are also astounded at their resilience.

Many of Aliu’s stories follow a pattern: A larger, horrible backstory is contrasted with a smaller scale distress in the front-story. Thus, a young woman whose mother is dying has her special moccasins stolen by a little girl; a boy whose family life is disintegrating, full of drugs and neglect, struggles to protect his pet insect; a woman coping with the death of her five-year-old daughter finds herself the unofficial foster mom to both a stray kitten and to the young man who lives next door. Aliu shows how these smaller moments take on greater import when all that lies beneath is already toxic. How can we be resilient through the small crises when the big ones loom so very large?

Aliu’s characters continue to believe that if only this one small thing could go well, maybe it would mark a change in fortune, a tipping point toward a better life. In the title story, a woman stays committed to community college even after the loss of her young daughter. In “Two Assholes,” a disgruntled housewife takes a course in Excel as an escape route from a miserable marriage. And so the wrestler keeps wrestling. The camp counselor makes it to college. Whether or not they would articulate it this way, these are people who have bought wholeheartedly into the American dream of hard work leading to a better future. The pain as a reader comes from seeing that the facts don’t exactly back up the rhetoric and the dream so lovingly tended may be illusory.

One of Aliu’s writerly talents is her ability to capture the rapid-fire thought processes of her characters, carefully wrought in their own vernacular. In the opening story, “You Say Tomato,” the narrator hits the ground running:

My mother ate taycos and tortillia chips. She had good idears. She said that Mac was playing Nytendo, that he needed some deroderizer for his pits, that my real father had told her his name meant warrior in Albanian, but it was actually more like Shit for Brains.

Many of the stories share this staccato cadence. The voices come at us loudly and insistently. Hear me. In all my ugliness, hear what I have to say. These voices talk fast, demand to be heard, and carry us along for the wild ride.

If there’s a release valve for the painful realities to which Aliu exposes us in story after story, it comes in the form of humor. The voices are sardonic or self-deprecating or just playful. In the title story, for instance, the narrator compares what she sees at her next-door neighbor’s house to her own in this way:

I couldn’t blame Danny for getting so fat, when his grandma was always next door cooking up eggplant parm and a different kind of cacciatore for every day of the week. It was all bacon fat and red sauce over there, and sometimes the smells creeping into my kitchen from hers made the macaroni-and-government-cheese I made three times a week taste better and sometimes just bitter.

The fast pacing and quick wit of Aliu’s narrators kept me entranced. These aren’t people I’m eager to be friends with—I certainly wouldn’t want to step into their shoes and live their difficult lives—but their vivid portrayal forces me to pay attention to them. To feel their pain. To validate their struggle.

If there’s one disappointment I had in the collection, it was that Aliu doesn’t take on class dichotomy as a theme of her stories, a potential missed opportunity. If it hadn’t been specifically mentioned that these stories were set in Connecticut, I doubt I would have recognized my home state. Connecticut is one of the wealthiest states in the US and has one of the lowest poverty rates; it also has one of the highest rates of income inequality. Aliu chooses to keep her stories entirely entrenched in their insular, financially starving world, a place that is interchangeable with the hundreds of other small cities in America for which economic depression is the norm, not a phase. If anything, the characters in these stories seem entirely unaware that another kind of life exists a few miles away.

But this authorial choice does not diminish the quality of Aliu’s powerful fiction. Her dark humor keeps us from being overwhelmed by the futility of her characters’ lives and her knack for choosing the just-right small moment within a life wrought with dysfunction brings her message home without becoming maudlin or preachy. This may not be the Connecticut you thought you knew, but I, for one, am grateful to see those velvet curtains drawn aside.

About the Reviewer

Jennifer Wisner Kelly’s stories, essays and reviews have appeared in the Massachusetts Review, the Greensboro Review, the Beloit Fiction Journal, Poets & Writers Magazine, Colorado Review, and others. She recently attended residencies at the Jentel Foundation, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. Ms. Kelly is the Book Review Editor for fiction and nonfiction titles at Colorado Review.