Book Review

I look away, a ridiculous retch rising—my friend keeps her eyes on the screen, bemused. We are watching “Mario Montez and Boy,” a short Warhol film, in which the famed drag queen Mario Montez and “the boy” Richard Schmidt share a burger together with increasing passion. It’s deliciously camp, the music written to accompany the film for this event rising to a crashing crescendo of squirting ketchup. Maybe it’s McDonald’s, maybe not, but that burger with its plastic cheese and dripping juices, making out with these people, consuming them as they are consuming, that burger turned my stomach. And yet I’ve eaten those burgers, I am a connoisseur of consumption. Avoiding the screen, my eyes flick around the theater, taking a straw poll of who is looking, who prefers to look away. The intersection of humor, consumption, grease, sex selling, and capitalism pulls us in as an audience and asks, what? Or, more importantly, where? Where are you placing yourself in this glorious mess?

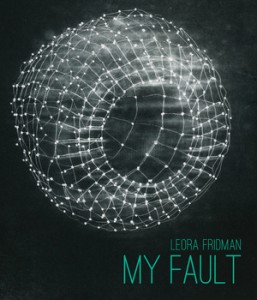

This space between play and consumption critique is a gulf from which My Fault blooms. In “Delicate Matters” we see consumption of the ocean, consumption of a woman, consumption of dying plants, and plastic consumption filling the deepest darkest landfill:

my conscientious

waste

meals as protectors

of broke chemistry

every ache sound

we can’t eat

becomes a cheap

solution

Fridman has no interest in didacticism. Though deeply invested in an examination of climate change and capital, the poems of My Fault position themselves firmly in the glorious mess of complicity. It is not that My Fault refuses the political, rather that these poems dedicate themselves to the idea that the personal is political. The “cheap / solution” is bound to the “we,” implicating the speaker and their own “conscientious / waste” in the poem’s wreckage. When, later, the speaker asks:

how could you

lessen levels

if you never

ever shame

we know that shame radiates both inward and outward, a question of effectiveness.

There is a devastating, at times deceptive, lightness to Fridman’s debut collection. Wild, skinny stanzas, dominantly couplets, skitter across the page but avoid sparseness. Though there are a few prose poems within the collection as formal outliers—notably the darkly comic poem “3D House of Beef”— a rangier sense of the line prevails. “To the Recent Sea” drops us a tiny ars poetica: “No meaning / is patient / with me.” It is easy to read an inheritance of imagism into My Fault—there is certainly the language of common speech, prizing of the image, and a commitment to concentration. The skinny stanzas of My Fault, however, use the white space to make huge leaps of metaphor. These poems are deeply invested not only in movement, but also in the act of connection, and of engagement.

An undergraduate professor once told me, at a time when a professor’s definition of a poem was still gospel, that “a single word cannot hold a line.” I don’t remember disagreeing—or if that cloud ever fully lifted before reading Fridman’s deft, brief lines that skip with joyful abandon while indicting the systematic destruction of environment, capitalism and its consumption. That professor’s statement rests on the possibility of dissection, of taking a poem apart to define its fundamental units. For Olson, it was the breath, for metrical poets it’s the foot. My Fault is not afraid to rest a line on a single word because no line is alone, everything must engage with its surroundings. A single line, just like a single person, is inextricably embedded in the systems in which it exists.

This engagement is rooted in a deep sense of ecopoetics. The epigraph from Alice Notley “Pained and similar plants, now don’t I have to / give?” serves as rallying cry and blueprint. Fridman’s fierce sense of connection, holistic, holy, and wholly consuming is predicated on interconnectedness. To be human is to be part of a family, to be part of an ecosystem, to be part of large and powerful system, to be caught in capitalism. In “My Dispersing Sorry” the declarative opening couplets

my new pledge

is I will matter

without

being fuel

mutate and writhe to become so much more complicit in their politics. The rousing call to individual resistance, the seemingly simplistic statement, shifts:

I am no middle America,

no quietly crucial selection

that remains to be made

between what rules us

The “I” that becomes “us” is a lost voice in the closing line: “as we forget one more pledge.” Beyond the crushing understanding of an idealism lost, what these seemingly tiny shifts do is open up the gulf alluded to in the title—the fault of it all. Geographical and geopolitical, the fault here is not apportioned nor claimed by a martyred speaker. In an interview solicited by the Library of Congress (but ultimately rejected and published by Bloof), the poet CAConrad addresses the uncomfortable friction between writing and citizenship: “No matter how many poems I write I cannot undo my complicity.”

Rather than search for absolution, Fridman writes into the complicity, into the fault. This is signaled early in the collection with “How to Hold”:

You normally feel regret

and are proud of

your ethics, but

when it comes to things

you can easily cover

with only your hands

you do not defend

them from yourself.

Poets are often praised in a frustratingly abstract manner for how they ask what a poem is, or what it can do. My Fault presents this as not an abstract question, but a pressing concern. In “Indoor Poem,” the delicacy wrought of “a hyacinth / in the garden of my dreams” is pierced with a question as to why one would assign value to this beauty—“I’m not proud of them.” The resounding final thought, “Every culture / has its decorative arts” charges this complicity. What can decoration do for an earth that dies?

What can poetry do to confront its environment when “no fault is our fault / just fractures in the land”?

About the Reviewer

Caroline Crew is the author of PINK MUSEUM (Big Lucks, 2015), as well as several chapbooks. Her poetry and essays appear in Conjunctions, Salt Hill Journal, and Black Warrior Review, among others. Currently she is pursuing a PhD at Georgia State University, after earning an MSt at the University of Oxford and an MFA at UMass-Amherst. She's online here: caroline-crew.com.