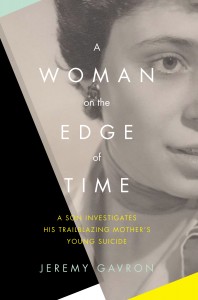

Book Review

As if writing a family memoir for public consumption isn’t difficult enough, Jeremy Gavron takes on an even higher challenge: to capture the life force of a mother he barely knew as he unravels the riveting story of her suicide. A Woman on the Edge of Time succeeds at being generous and skillfully constructed—“part fairy tale, part detective story, magic and ordinary at the same time”—by virtue of the author’s meticulous and persistent research. Gavron may have written a personal inquiry into what he describes as “the hardest human act to understand,” but by presenting his findings with great openness he allows readers to recognize themselves in his book. Of all the stories we hear in our lifetime, with all their imperfections, those that become required reading reward us with the gift of insight. Here Gavron’s major achievement is insightfully delivering this literal “story of his life” with the intrigue, if not pace, of a thriller.

As if writing a family memoir for public consumption isn’t difficult enough, Jeremy Gavron takes on an even higher challenge: to capture the life force of a mother he barely knew as he unravels the riveting story of her suicide. A Woman on the Edge of Time succeeds at being generous and skillfully constructed—“part fairy tale, part detective story, magic and ordinary at the same time”—by virtue of the author’s meticulous and persistent research. Gavron may have written a personal inquiry into what he describes as “the hardest human act to understand,” but by presenting his findings with great openness he allows readers to recognize themselves in his book. Of all the stories we hear in our lifetime, with all their imperfections, those that become required reading reward us with the gift of insight. Here Gavron’s major achievement is insightfully delivering this literal “story of his life” with the intrigue, if not pace, of a thriller.

In the opening pages of the book, we learn the facts of Hannah Gavron’s death as they were reported in the Camden & St. Pancras Chronicle of North London in December 1965 when the author was four years old. He crafts the details using the distance necessary for him to stay passionate and purposeful as the memoir’s narrator and main character. Having been led as a child to believe that his mother had died in a car crash, Gavron finally learns the truth from his father when he is sixteen. It isn’t until fifteen years later when coincidences between his brother’s death and that of the son of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath compel him to write an article for The Guardian. Replies he receives in response to the article serve as a catalyst to new discovery and revision of his reflections. He pieces together Hannah’s life like an archeologist, “making due with fragments to construct a whole.” On his obsessive journey, he races through her past seeking answers from those who knew her, each time revealing something new. He follows leads that allow him to construct this woman who is “clever,” “intense,” “fascinating,” and “fierce,” with “film star vitality,” and yet “easily bored,” “needing excitement,” and “narcissistic.” We inevitably gain an interest in Hannah as if she were someone we used to know. In fact, her life has all the trappings of a real-life manic pixie dream girl: a once-tomboy with a countryside gang who became the “most interesting person” in her coed boarding school and then an actress in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and finally, an unfulfilled intellectual, completing a PhD and pursuing the publication of her expanded thesis. The tension is made more palpable because we do not forget that we are seeking the reasons why a Jewish woman born into the second World War gassed herself at age twenty-nine, leaving her husband and two young boys behind.

Unraveling family secrets makes for a good narrative engine. Some of what Gavron discovers deepens the mystery, but it is ultimately his ability to sustain a story with a stated lack of conclusiveness that keeps the reader on edge. By developing layers of information he gives us greater understanding of suicide’s complexity and Hannah’s character. Halfway through, he voices the question that remains just below the surface of the text: “How do you remember someone who erased herself? How do you mourn someone who so completely rejected you? How do you carry on your own life in the face of such a thing?” When Gavron enters what he calls “Hannah’s part of the story” in the final third of the book, we discover that her found letters are those he has already been using to structure the book, so we revisit what has already been revealed in narration. From the outset we are subject to the twists and turns of many plausible subcontexts that have a humanizing effect on a son’s search for meaning, so that by the end when we count eight different theories about why Hannah took her life, there is no awkwardness about displaying this, warts and all, because its clear purpose is to give life, the purpose of all writing.

Death is the final act before falling off the edge of time. What Gavron has created is an investigation of a life and all the people affected by that life. In his own final act, we get the “narrative verdict,” an inventive adaptation of a recently devised English coroners’ court report “used in instances where the cause of death, or the responsibility for that death, cannot be easily categorized,” not granted in Hannah’s case. It reads like summation, but it is a unique literary maneuver. The attentive reader has felt Gavron’s narrative engine getting them somewhere and now the “why she killed herself” comes as a long list of ideas like a twisted Keatsian truth, one that eludes Hannah when she says to her father before her death: “Ideas are no use to anybody today: you’ve got to have something, to be a scientist, a physicist. Just ideas are no good any more: you need the machinery to carry them into effect.” By Gavron’s self-admission he is the “least qualified to write this but” writing and revision bring him to his final purpose. In the end this is the song of a motherless child who needs to write things down, who doesn’t memorize entire conversations. We do what we can with our ideas. When Gavron’s desire to relate, confess, and investigate come to an end, his effort allows us all to settle into the life before us. His work is essential for anyone struggling to make sense of the past.

About the Reviewer

Gil Soltz lives in Paris, France and is the founder of the Yefe Nof Residency in Lake Arrowhead, California. He is the author of the self-published 2015 “promonostory,” Inspiration Drive.