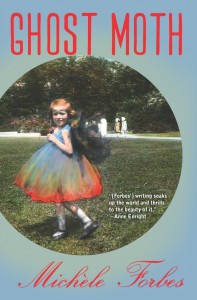

Book Review

The soulful black orbs of a seal’s eyes are enough to move most emotionally functional people to pity and concern—think the baby-white seals of the anti-fur campaign—but that’s not the reaction of Katherine Bedford in the opening scene of Michèle Forbes’s exceptional debut novel, Ghost Moth. Instead, when Katherine swims too far from shore and finds herself face to face with the “great gunmetal gray head” of a large seal, the seal’s “huge, opaque, and overbold” eyes terrify, not charm, Katherine, and “hold on her like the lustrous black-egged eyes of a ruined man.” In Forbes’s deft hands, tension rises precipitously as the two creatures silently bob in the ocean swell, just staring, and Katherine becomes as frightened by what she can see above the water as what she cannot see beneath her: “She thinks of everything under the surface of the water. Just under the surface. Just right there. Any amount of things to pull her down.”

The soulful black orbs of a seal’s eyes are enough to move most emotionally functional people to pity and concern—think the baby-white seals of the anti-fur campaign—but that’s not the reaction of Katherine Bedford in the opening scene of Michèle Forbes’s exceptional debut novel, Ghost Moth. Instead, when Katherine swims too far from shore and finds herself face to face with the “great gunmetal gray head” of a large seal, the seal’s “huge, opaque, and overbold” eyes terrify, not charm, Katherine, and “hold on her like the lustrous black-egged eyes of a ruined man.” In Forbes’s deft hands, tension rises precipitously as the two creatures silently bob in the ocean swell, just staring, and Katherine becomes as frightened by what she can see above the water as what she cannot see beneath her: “She thinks of everything under the surface of the water. Just under the surface. Just right there. Any amount of things to pull her down.”

This powerful opening scene sets the stage for a novel that explores the mysteries that lie beneath the surface of Katherine, a Catholic mother of four living in Belfast in the summer of 1969, when the “Troubles” began in Northern Ireland. The city’s unrest is a fitting and complex foil to Forbes’s portrait of Katherine, who, in mid-life, struggles to find peace for her own troubles: a wrenching conflict between loyalty to a love that might have been—one imbued with erotic tension and passion—versus commitment to a love lived.

Forbes’s narrative moves back and forth between 1969 and 1949, slowly revealing the troubled past that is the foundation of Katherine’s present reality. In 1949, Katherine, an employee in the Ulster Bank, was dating George Bedford, the man who would become a dependable civil servant, volunteer firefighter, and ultimately, her husband. But Katherine was also an amateur opera singer who, during a production of Carmen, encountered Tom McKinley, a costume tailor. After a sudden, secretive kiss, Katherine found herself having tea with Tom: “She was enthralled by the way in which he seemed to draw joy from everything around him. Her world seemed wider.”

Forbes is a master of creating high tension and drama in the simplest of movements and actions. Like the opening scene with the seal, in which the only action is the fixed gazing of the two bodies in the water, Katherine’s first meeting with Tom is as quiet and subtle as a whisper, yet completely captivating. Katherine stood virtually motionless as Tom took her measurements: “His touch was as light as a barely spoken prayer. But the more still she was, the more intense it felt.” The description of the fitting and Katherine’s steadily growing arousal lasts for three and a half gripping pages without ever sinking into sentimentality.

In spite of feeling that “something new was opening up within her” with Tom, Katherine returned home after her tea with the tailor and found George waiting for her, ring in hand. She hesitated, but then thought: “She knew George…She knew his ways, trusted him, relied on him, knew that he loved her and would care for her. Here is a decent man. Here is George.” Katherine accepted his proposal.

While Katherine’s engagement does not immediately end her exploration with Tom, she does ultimately end the affair. She marries George and becomes a committed and satisfied mother: soothing sunburns, organizing picnics, and playing nighttime rounds of chicken shadows. Nevertheless, tensions bubble beneath the surface of this seemingly tranquil domestic soup as Forbes carefully adds and mixes the ingredients of Katherine’s quiet present with her unresolved past, including a mystery surrounding the end of her affair with Tom.

One of the strengths of the novel and the key to the mystery of Katherine’s past, however, is that Forbes does not allow her characters to fall into neat and tidy categories. Katherine has much more to choose between than just the magical versus the mundane. She discovers that Tom’s magic may not be all that it appears to be, and George, too, is not as predictable as she has come to expect. As a result, Forbes creates characters and situations that feel authentic. Life here is both messy and mundane, and, at times, transcendent.

Forbes’s novel is further enriched by her use of powerful imagery. From the crystal-clear description of the seal to the delicate portrayal of a porcelain statuette and the details of an old black and white photograph, Forbes has the eye of a poet, painting a vivid world in which the ordinary is chock-full of mystery. However, Forbes suggests that finding meaning behind the ordinary is, like most things in life, a question of choice. For example, one morning before dawn, Katherine sits with her daughter, Elsa, and describes her experience as a child of waiting for ghost moths to appear. She tells Elsa how she lay down in the garden and watched “[p]ure-white moths rising and falling above the grass, as if they were dancing, moving toward me, hovering over me.” One time the moths landed on her, covering her from head to toe. She says to Elsa: “I remember thinking, This must be what it feels like to be in Heaven.” Katherine’s father had told her at the time that “some people believed that ghost moths were the souls of the dead waiting to be caught, and some people believed that they were only moths.” When Elsa pushes her mother to say which she believes them to be, Katherine is unable to respond, unsure as she is of how, or if, she will find meaning in recent and past events in her life.

The tension between Katherine and George deepens as they each struggle to decide what meaning and weight the past will have for their present, and this emotional conflict is mirrored in the real-life political struggles and violence in Belfast in 1969. The “Troubles” reached a peak in August of that year. Unionists and republicans, frustrated with Parliament’s lack of movement to address social and political ills such as institutional discrimination against Catholics, clashed violently. The situation became so severe that British troops were sent in to restore order. Forbes weaves these realities into her narrative insofar as they impact Katherine’s life. She wakes one morning to see from a distance gray smoke pluming above the city. “What in God’s name is happening? She wonders. Riots in the streets, petrol bombs, cars and buses burning?” Subsequently, the impact strikes closer to home. The local grocer’s shop is burned by a petrol bomb, and Katherine is spit upon on the street for being a “Fenian,” a slang term for Catholics and nationalists. Katherine’s daughters are also not spared. In one instance, walking home from school through a Protestant neighborhood, they are pelted with eggs in spite of the fact that all “clues that they are Catholic are, as usual, covered by their navy coats,” suggesting that some things cannot remain hidden.

Ghost Moth is a compelling novel with a sharp emotional lens that rarely loses focus. Katherine’s experiences remain authentic yet are touched by an Irish sensibility of faith, and Forbes’s poetic imagery is consistently and powerfully poignant. As the story nears its resolution, however, several scenes make us worry that Forbes might try to guide her story too neatly back into the harbor and secure any loose lines to the dock. Fortunately, she resists this temptation and allows her story to moor offshore long enough to suggest that the complicated journey will continue.

Ghost Moth suggests that life is really all about choices. In the end, as Elsa rides in the back of a car past the burned out grocery store, she reads the slogan painted on the wall: “The Past Is Not Quite Past.” “Elsa wonders what it means. Then she puts her hand up against the window and blots it out. Now she can no longer see it.” Like Elsa, we have a choice, not just about whom we choose to love or what we choose to believe, but, more importantly, how we will love, how we will remember, and how, if possible, we will forgive.

Posted April 10, 2014

About the Reviewer

Susan Donnelly Cheever is an English teacher and poet. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts.