Book Review

Recent years have seen a proliferation of highly specialized anthologies within the field of Ecopoetics and environmental writing more generally. For example, Camille Dungy’s Black Nature, published in 2009 by the University of Georgia Press, documents four centuries of African American nature poetry, offering readers a concise window into the genesis and evolution of a particular area of environmental writing. Likewise, G.C. Waldrep and Joshua Corey’s 2012 anthology, The Arcadia Project, collects the work of contemporary poets (Joshua Harmon, Forrest Gander, and Timothy Donnelly, for example) responding to and reworking an inherited tradition.

Recent years have seen a proliferation of highly specialized anthologies within the field of Ecopoetics and environmental writing more generally. For example, Camille Dungy’s Black Nature, published in 2009 by the University of Georgia Press, documents four centuries of African American nature poetry, offering readers a concise window into the genesis and evolution of a particular area of environmental writing. Likewise, G.C. Waldrep and Joshua Corey’s 2012 anthology, The Arcadia Project, collects the work of contemporary poets (Joshua Harmon, Forrest Gander, and Timothy Donnelly, for example) responding to and reworking an inherited tradition.

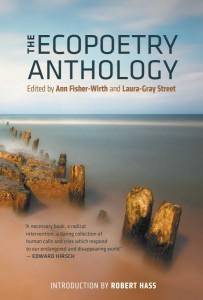

With that in mind, Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street’s The Ecopoetry Anthology offers a much needed overview (and reframing) of the tradition of nature poetry as a whole. Published in 2013 by Trinity University Press, the volume includes several critical essays, written by the co-editors and award-winning poet Robert Hass, which offer readers an overview of the various scholarly approaches to ecopoetry. Although the volume positions itself as a general introduction to the field, readers shouldn’t be fooled by the editors’ modest claims. The Ecopoetry Anthology offers a radical intervention into existing approaches to canon formation and scholarly interpretation.

What’s perhaps most useful about The Ecopoetry Anthology is the series of critical prefaces, which, rather than attempting to forge a cohesive definition of ecopoetics, acknowledge a variety of approaches to (and relationships between) poetry and the environment. These critical essays portray ecopoetry as operating at the nexus of many different literary and cultural influences, ranging from modernist poetry to science, astronomy, and geology. Robert Hass’s “American Ecopoetry: An Introduction,” for example, explores how “the human imagination in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has been absorbing many possible meanings of what astronomy has to tell us about the universe, what geology has to tell us about the earth, and what evolutionary biology has to tell us about life.” I find it fascinating that Hass presents ecopoetry as an interdisciplinary space, in which writers may explore the various relations between and resonances among different disciplinary approaches to understanding our surroundings. Like all of the critical essays that preface this volume, Hass’s “American Ecopoetry” offers a critical lens that elucidates, while at the same time complicates, the texts contained in this well-designed and carefully conceptualized volume.

Indeed, the editors’ careful planning seems especially evident in their selection and inclusion of many core texts since the environmental movement of the 1960s, as well as historical texts (what Hass terms “great poems”) that represent the tradition with which these poets were in dialogue. Many of these earlier texts, presented in a section labeled as “Historical,” are crucial for understanding and contextualizing the contemporary poems that appear later in the volume. For example, Dickinson’s work (particularly “#116/328” and “#126/348”) provide illuminating formal and thematic contexts for approaching Jane Mead’s much later piece, “The Origin.” In much the same way that Dickinson uses dashes to fragment and rupture the poetic line, suggesting the impossibility of a single voice accounting for all of nature’s grandeur, Mead implements a similar formal strategy in her piece, using dashes and fragmentation to evoke the speaker’s diminutive stature in relation to the natural world. Mead writes,

Twice I have walked through this life—

once for nothing, once

for facts: fairy-shrimp in the vernal pool—

glassy-winged sharp-shooter

on the falling vines. Count me—

among the animals, their small committed calls.—

Count me among

the living. My greatest desire—

to exist in a physical world.

What’s most interesting about this passage is Mead’s use of Dickinson’s formal choices to address contemporary environmental concerns. Mead speaks of a world that is becoming increasingly technologized and less “physical” by the moment. I find it fascinating that Mead builds on Dickinson’s work, placing her formal choices in new syntactic and thematic contexts. In many ways, the structure that Fisher-Wirth and Street have envisioned lends itself to these kind of connections and resonances. While one might object to such a sharp divide between “historical” and “contemporary” texts, it seems necessary to create some temporal boundaries within the anthology, as these poets write from vastly different social, political, and aesthetic backgrounds.

The sections of the anthology that include contemporary writings represent a wide range of aesthetic choices and sociopolitical approaches to pressing environmental questions. For instance, Jennifer Chang’s “Geneology” and Tony Hoagland’s “Romantic Moment” present a radical, yet at the same time necessary, contrast. Chang’s poem, as finely crafted as it is meditative, presents a speaker who stands “stock-still as the trees,” suggesting the ways that the natural world fosters reflection and self-awareness. Hoagland’s piece, on the other hand, explores the myriad ways in which the natural world makes possible various personal and social relationships. He writes:

Instead we sit awhile in silence, until

she remarks that in the relative context of tortoises and iguanas,

human males seem to be actually rather expressive.

And I say that female crocodiles really don’t receive

enough credit for their gentleness.

Then she suggests it is time for us to go

do something personal, hidden, and human.

Hoagland suggests the myriad ways in which the natural world facilitates, and is woven into, social interactions and personal relationships. In many ways, this piece presents a radical contrast to Chang’s meditative and solitary “Genealogy.” Fisher-Wirth and Street have successfully curated a collection that represents vastly different perspectives on the natural world and our relationship to our surroundings. The fact that such different worldviews coexist within the same volume speaks to the editors’ concerted efforts to create a well-rounded, comprehensive, and representative anthology.

With that in mind, The Ecopoetry Anthology seems a necessary and useful addition to recent publications within the field of ecopoetics and environmental writing more generally. Fisher-Wirth’s and Street’s anthology provides useful and illuminating context for more specialized volumes in the field that appeared shortly before their own. In short, The Ecopoetry Anthology is a beautifully constructed, carefully planned, and intelligently framed volume. Readers looking for a concise introduction to the field of ecopoetry, or a thought-provoking intervention into contemporary scholarly approaches to ecopoetics, will find this book a worthy addition to their library.

Published 4/1/2014

About the Reviewer

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of seventeen books, which include Melancholia (An Essay) (Ravenna Press, 2012), Petrarchan (BlazeVOX Books, 2013), and a forthcoming hybrid genre collection called Fortress (Sundress Publications, 2014). Her awards include fellowships from Yaddo, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and the Hawthornden Castle International Retreat for Writers, as well as grants from the Kittredge Fund and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is currently working toward a Ph.D. in Poetics at S.U.N.Y.-Buffalo