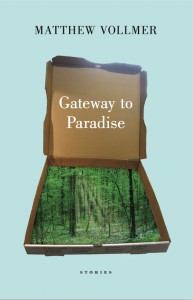

Book Review

Matthew Vollmer’s sophomore collection of stories is bright, sharp, au courant, and thoroughly enjoyable: six stories, all of them well made and a little edgy but by no means horrifying. A few of his characters experience something like pratfalls, but they also possess an earnestness that makes us feel a fondness for them. One of the things Vollmer does best is highlight and sustain an act or relationship that would seem outrageous if he did not also immediately pull the reader back to everyday reality. The trick is slick, but it works, and in the meantime, his characters deepen and become memorable, especially in the last and longest story, “Gateway to Paradise,” where a youngish woman named Riley saves herself. Or is she saved by the religious family that prays for her in Gatlinburg?

Matthew Vollmer’s sophomore collection of stories is bright, sharp, au courant, and thoroughly enjoyable: six stories, all of them well made and a little edgy but by no means horrifying. A few of his characters experience something like pratfalls, but they also possess an earnestness that makes us feel a fondness for them. One of the things Vollmer does best is highlight and sustain an act or relationship that would seem outrageous if he did not also immediately pull the reader back to everyday reality. The trick is slick, but it works, and in the meantime, his characters deepen and become memorable, especially in the last and longest story, “Gateway to Paradise,” where a youngish woman named Riley saves herself. Or is she saved by the religious family that prays for her in Gatlinburg?

Another adjective I might use—if it is not already old hat—is hip. Yes, these stories are hip. They are hip to slang, to youth, to the sadness of trying to find one’s self and one’s place in life. They are also hip to love and loss and the fear everyone has, especially when young or fairly young, of being alone.

In the first story, “Downtime,” a dentist is haunted by the loss of his wife, Tavey, who drowned on their honeymoon. We find this out in the first paragraph. Ted Barber, the dentist, had to fly back to Valleytown, North Carolina, knowing that his wife’s body was stowed in the cargo bay. He is now having a hot affair with his assistant, who is formidably competent and would be a great wife, but images and reminiscences of Tavey keep pulling him away. He finds a solution, or perhaps it is a resolution, but it is far from paradisiacal, and the reader continues to worry about him.

In “Probation,” the man on probation, one Abe Tucker, seems to be that last person in the world who should be on probation. He cares about his daughter and son, which makes us care about him. Wanting to do the right thing, he appeals to us, to our own better instincts. He has been waiting for his twelve-year-old daughter to get home. She’s three hours late, and he is trying to block images of car wrecks and child molesters from his mind, but he is shackled to an ankle bracelet. His crime was pointing a laser at a helicopter. Which led to more than a little trouble. Which led to a lot of trouble.

Abe lives in Valleytown, as Ted Barber does, but they don’t seem to know each other. Abe certainly has more than enough on his mind: daughter, said to have “licked” (not in the sense of “beat”) a guy; son, needs to interview his dad for a school assignment and wants the scoop on the laser; wife, Gina, with whom Abe is having a “trial separation” after she was seen by half the town having sex with an older man on a security videotape.

Clearly, some of these stories are riotous and will make you laugh out loud. “The Visiting Writer” is, on the other hand, less riotous than one might expect. The visiting writer is an older woman, and the person designated to drive her around and keep her on schedule is an untenured faculty member of the local university who will be handing over to the visitor a check for ten thousand dollars at the end of the visit. (I don’t know many small universities that can pay that kind of money.) After he picks her up at the airport, they eat dinner together. Our professor politely orders for himself “spinach salad with tofu,” by way of establishing himself as sensible and intelligent. The visitor orders duck, and soon they are sharing the duck. They have a smoke, “a desiccated-looking Parliament.” He notes to himself that she is “simultaneously fragile and strong.” Indeed, “Her bones, I imagined, were not unlike those that allowed certain birds to soar and glide: hollow, but durable.” In short, he is falling for her, although he has a wife and young daughter back home. “A heat-flume ignited inside my chest,” he tells us. “I felt myself teetering on the brink of some preordained transgression, one composed by whatever Author was writing the script of my life. . .”

“Dog Lover” and “Scoring” are stories that plainly exhibit the “slick trick” I mentioned earlier. The first involves a young woman with an oblivious husband, a dog, and a jar of peanut butter. It includes a sentence that extends over many lines, exaggeration that renders the outcome all the funnier. Is it gross? A bit, but that only makes it more memorable. “Scoring” is more complicated, taking place at a conference in Daytona Beach of teachers who grade Advanced Placement essays (hence the pun of the title: the students get scores, the teachers dream of scoring with women). Martin Ernest Postachian, aka “Stash,” encounters Inge, a manicurist and kiosk-managing free spirit with “[a] beatific smile that reveals an adorable overbite.” Are the guys in this book attracted to every woman they meet? Pretty much yes, but they also suffer consequences. Inge makes an announcement: “I’m not bisexual. At least not when I’m sober.”

Stash is another dreamer. He dreams of “a state of unadulterated carnality.” (The men in these stories are all somewhat Walter Mitty–ish, though their dreams partake of more sexuality than Walter Mitty’s.) But Stash also sees, on Inge’s face, “an expression he sometimes sees on [his son’s] face, when Stash comes in to straighten his covers and falls in love with him all over again. . .” And as he dreams this waking dream, he remembers his wife, Dana, and their wedding vows.

The book closes with the title story, also set in Gatlinburg, and also including prayer. Here at the end, the stakes are raised. Someone is killed; someone is left behind; someone reclaims her life. Nothing is a slick trick, and paradise—until now a place in which to vacation or to sing a song, or maybe to share a toke—takes on gravity. There are still jokes and wordplay, but Vollmer’s larger vision is of men and women who struggle, suffer, and don’t always, or barely, escape.

Gateway to Paradise is fun to read and even more fun to think about after you’ve read it. This is the case even with the last, moving story because Riley sees the light and saves herself.

About the Reviewer

Kelly Cherry is author, most recently, of Twelve Women in a Country Called America: Stories.