Book Review

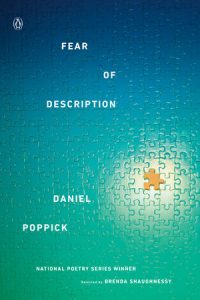

Daniel Poppick’s second collection, Fear of Description, features a collection of sonnets, elegies, and autobiographical essays that examine both a crisis of a generation and a crisis of the self. Through a careful examination of formal restrictions as a means of accessing truth, Poppick attempts to establish trust and beauty within language. In these tests of form, intended to act as catalysts toward a construction of meaning and order, he hopes to uncover a promise of salvation from a broken existence. Instead, Poppick finds himself confounded and unredeemed:

Daniel Poppick’s second collection, Fear of Description, features a collection of sonnets, elegies, and autobiographical essays that examine both a crisis of a generation and a crisis of the self. Through a careful examination of formal restrictions as a means of accessing truth, Poppick attempts to establish trust and beauty within language. In these tests of form, intended to act as catalysts toward a construction of meaning and order, he hopes to uncover a promise of salvation from a broken existence. Instead, Poppick finds himself confounded and unredeemed:

It occurred to me, trying to block out the sounds of a baby crying in the waiting room and construction workers chanting reasonable demands outside, that poetry would not save my life, as I had expected, in the end, it would. On the contrary, sitting there I realized that something called “poetry,” loosely sketched from what I imagined that word to mean when I was a teenager . . . might in fact at some point down the road play a hand in killing me.

Much of Poppick’s work roots itself in tradition, both in its content and formal restraint. The collection opens with a sonnet called “Red Sea,” in which Poppick calls upon Hell, a pharaoh, and an unidentified queen. He brings these traditions forward to the contemporary sphere, utilizing these figures in juxtaposition to modern issues. Poppick immediately establishes his apprehensions in saying, “I’m terrified of a number of fates” and “Committing a thought like this to the page,” positioning the reader to be wary of the anxieties he will investigate throughout the collection.

The reader is granted entrance into Poppick’s consciousness frequently. “Rumors,” the first essay to appear, brings forth an awareness of memory’s ability to fail, then persists despite its imminent doom. Details are misremembered and only sometimes corrected, leaving the reader unsteady in their ability to believe the speaker. Poppick, however, capitalizes on this instability by admitting mistrust within himself, exemplified when he says, “Was it even raining? No, the stars were out. The only games I like negate competition. I wonder what I mean by that.” The reader, through lines like this, begins to feel a sort of empathy for Poppick, as they watch him plow through a narrative in search of meaning that perhaps does not exist. Language proves itself a means of access to further questioning that may hold more truth than the answers in which he desires. The difficulty is not that there is no answer, but that there are too many.

The unfurling of Poppick’s ability to control language in a meaningful way continues in the elegy “Aries,” where he plays on the astrological sign’s significance in that it prescribes fate, removing agency from our lives. He writes:

I think language, for me, is a tool of differentiation from my bloodline

Bound to break down and fail.

Language chooses what to say with you,

It says the waves, reiterated crimes.

At this point in the text, Poppick appears to have surrendered all hope of authority over language. He sees himself as a plaything of language, a plaything of fate. The brevity of this claim comes in calling back to the first line of the entire collection when Poppick stated, “I’m terrified of a number of fates.” The reader recognizes the tragedy in Poppick’s succumbing to fate through language, instead of being able to use language to create order and meaning.

As the collection progresses, a distance begins to develop between an action taking place in the world and the subsequent emotional reaction that is induced. Time begins to feel slippery, as Poppick fails to recall the sequencing of events, with psychological turmoil appearing well after an event taking place. This theme culminates at the end of the essay “A View of Vesuvius,” where numbness is expressed through metaphor. The essay concludes:

When I left my boss’s apartment for the final time I locked the door behind me, and from the other side of the space sang, YOUR SYSTEM IS ARMED. I hope you also have

a blank space between

your head and feather pillow

that’s automatic

In this instance, Poppick is using the metaphor of both a security system and the hope for an “automatic” and “blank space” between pillows to create psychological distance between trauma and feeling.

With the final essay of the collection, “The Hell Test,” Poppick explores trespassing on property, using a large estate as a metaphor for syntax. He sees himself as “of” the ruined estate, and therefore “of” the syntax he has been grappling with throughout the collection. A tragic realization is made when Poppick says, “poetry would not save my life, as I expected, in the end, it would.” The reader has watched language and syntax fail through the entire collection, then is struck by the tragic reality that in fact poetry cannot save us. To Poppick, we are playthings of language, failed messengers trying to make sense of broken lives and a broken generation. Fear of Description is a magnificent calamity of what language cannot be, no matter what we believe it could (or should) provide.

About the Reviewer

Jack Berning is a writer and graduate student at Colorado State University, pursuing an MFA in poetry. He currently lives alone in Fort Collins, Colorado.