Book Review

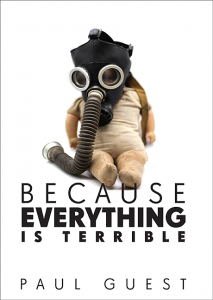

In Paul Guest’s fourth collection of poems, Because Everything Is Terrible, doom is never far away. It isn’t all rapturous, of course—mushroom cloud and debris—rather, it’s something that waits for you at the end of each day. Doom comes in small doses: Norway turns off its FM broadcast, a local doughnut shop closes after decades, your father hoses down his car after hitting a stray cat. This is the world in which we live, full of minor tragedies collected like change at the end of the day, pocketed or left on a nightstand. It’s ordinary and—in its own way—completely debilitating.

In Paul Guest’s fourth collection of poems, Because Everything Is Terrible, doom is never far away. It isn’t all rapturous, of course—mushroom cloud and debris—rather, it’s something that waits for you at the end of each day. Doom comes in small doses: Norway turns off its FM broadcast, a local doughnut shop closes after decades, your father hoses down his car after hitting a stray cat. This is the world in which we live, full of minor tragedies collected like change at the end of the day, pocketed or left on a nightstand. It’s ordinary and—in its own way—completely debilitating.

Guest opens the collection with “After Damascus,” a massive thirteen-part, twenty-one-page poem that sweeps the reader between wild scenes, examining the absurdity of everyday life. “The yearning you felt made no sense,” Guest writes as the speaker bounces from a distant war to karaoke bars to watching John Wayne movies and feeling something akin to grief. The poem is both restless and dreamy, ultimately feeding on the dark humor and collapsible encyclopedic scope that has become Guest’s trademark:

You know you’ve already been defeated

at chess, in tennis, in the dojo of an inscrutable master.

You smile. Your teeth ache.

You wonder why.

Indeed, “After Damascus” leans into all of America’s heat and noise to examine just how absurd and grotesque life within it has become.

Beyond exploring this frenzied state, “After Damascus” investigates how one moves forward in a directionless-feeling era. The poem opens with an epigraph from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, taken from the moment Huck turns his back on the church to save his friend and runaway slave, Jim: “All right, then, I’ll go to Hell.” Indeed, in this labyrinthine poem, the speaker stares down the barrel of a new life and questions whether or not it will lead to fulfillment. In one section, when a jellyfish washes up on the beach, the speaker—curious or bored—punctures its body with a stick, and thinks, “You regretted the harm, / completely, though the thing was nerveless, cold. / You walked back.” The poem forces its reader to consider: How do we learn tenderness when we, as a society, are insensitive to war and violence? How do we learn to grieve? How is it possible to slog forward knowing the intensity of our own nameless suffering and the suffering of others?

Each of these minuscule yet vulnerable moments, in turn, challenges the speaker’s philosophy on living well. In the first section of the poem—which occurs in the midst of war—the speaker calls soldiers from an opposing government “sweethearts,” learns about their mothers, and now must consider, who are the good guys anyway? Just as the poem’s title indicates, this layered piece is its own road to Damascus: an opportunity to consider and reconsider one’s sense of right and wrong, to measure guilt against redemption. Every day, the poem seems to indicate, is a new opportunity to come to terms with oneself, even if that means resigning oneself to hell just like Huck.

And while this collection works in the wake of Mark Twain and the Bible, it’s ultimately forged for the present moment. The collection understands what’s at stake—what living in America in 2018 means—and is determined to make sense of such chaos. In “Inaugural Poem,” Guest’s language reads with a caustic, almost Ginsberg-like tone as it attempts to coax the country back to whatever it was before:

America, spare me,

would you, this blinding headache

and this sense

that nothing will be again

as it once was.

Likewise, in “If Nothing Else This Poem”—a poem dedicated to Heather Heyer, the woman murdered at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville—Guest lays out how hopeless everything feels at both the personal and societal levels: “Yes, something somewhere is / burning down. You will lose / everything. Some day. This is not news.” The poems in this collection are frustrated, mourning all the beauty and optimism that has somehow slipped through our fingers.

And yet, even as these poems wade through immense pain and suffering, they somehow compel the world into song. In his tremendous “All-Purpose Elegy,” Guest weaves together a litany of what’s worth grieving:

For the sun, which will burn out or run down

or dramatically implode in a future

epoch about as awful as this one. For

the one-antlered deer that expired en-route

to an upstate sanctuary because

why not. For the sequoia tunnel tree

which was uprooted in a storm

the other day. For my boyhood fantasy

of driving through it.

Although the details collected are tragic, the poem stands as an excellent example of how elegy, at its core, is meant to celebrate what must be celebrated. Rather than feeling like a funeral, much of the collection feels like a séance, attempting to bring back the past until we can almost sense its familiar presence, if only for a moment.

In the final section of the collection, Guest switches gears and attempts to redeem the world he has laid out. While the first two sections interrogate how the personal intersects with the political—how to appropriately grieve what’s out of anyone’s control—Guest ends the book with meditations on love and peace. It should feel sappy, but it doesn’t; instead, the poems examine what it means to care for anyone in a world that cares so little for us: “For your body. For the sum of all your cells. / The billions which you are. / This is a poem.” Outside, the world still looms, giant and brutal. We remain in the midst of a feverish political moment. And yet, in these final poems, there is a sense of ease. Love, perhaps, can save us—or at least make all that is unbearable bearable.

In Because Everything Is Terrible, Paul Guest reminds us what has made him such a refreshing and illuminating voice for years. These are urgent poems, made all the more urgent by the apocalyptic-feeling political landscape we’ve entered. They overflow with a wondrous kind of dread. These are the poems we need in 2018: skeptical and solemn, tongue-in-cheek, and yet, always big-hearted. Always desperate to praise all that can possibly be praised: Dragonflies mating in flight. Waking beside your beloved. How the stars hang in the sky whether you look for them or not.

About the Reviewer

Rob Shapiro received an MFA from the University of Virginia where he was awarded the Academy of American Poets Prize. His work has previously appeared or is forthcoming in the Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, River Styx, Blackbird, and Pleiades among other journals. He lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.