Book Review

As the first story in Tom Williams’s new collection opens, a dejected writer sits alone in a fried chicken joint contemplating his latest magazine rejection—this time from “an on-line number, Boning the Muse”—when he hits upon an idea that will solve his financial and creative woes in one stroke. His face “slick with sweat and tears,” he decides he’ll finally write from his heart and commemorate this delicious meal, a three-piece combo with drink, in fiction. Best of all, he’ll get the restaurant chain to pay for and publish it. His intentions are sincere—to write “a novel of art, love, and fried chicken”—but like all the schemers in Williams’s stories, he runs the risk of being destroyed by his creation.

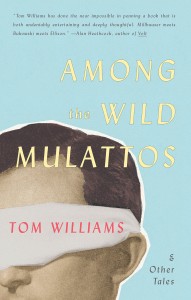

“The Story of My Novel, Three-Piece Combo with Drink” sets the tone for a book that uses high-concept premises to explore down-to-earth questions about identity, cultural intersection, and personal ambition. Among the Wild Mulattos & Other Tales is set almost entirely in a region called the Mid-South, an in-between place appropriately filled with characters who are neither here nor there—not successful and not abject failures, not happy and not sad, not black and not white. Most of the stories are narrated by bi-racial men whose skin color serves as a kind of extreme social camouflage. They find themselves either utterly ignored or ostentatiously singled out, and nothing they do is good enough for those who police their behavior. While frequently funny and surprising, a sense of melancholic dislocation pervades these stories, lending gravity to the outlandish scenarios Williams imagines.

A few short pieces provide a change of pace, but it is the longer stories that are most memorable. In “Movie Star Entrances,” perhaps the funniest, strangest, and most haunting piece here, accountant Curtis Jenkins seeks a desperate remedy for his anonymity and social isolation in the workplace. With the annual office party looming, Curtis hires oddball makeover artists Ramon and Miriam to coach him in making an impression. They outfit him with “a majestic seersucker suit, an item Curtis had never dreamed of owning,” a straw boater, and a hidden speaker system that plays only Professor Longhair’s “Tipitina.”

But the process of giving Curtis “a sense of mystery and intrigue” turns into a referendum on his very humanity. Miriam tells him dismissively: “We make it possible for the most ordinary person to become extraordinary,” but almost immediately she and Ramon fall into a routine Curtis is all too familiar with.

Go ahead and ask, Curtis was thinking. And she did: “Jenkins,” she said. “That’s what, an English name?”

Curtis didn’t want to play at guessing, so he volunteered, “I’m biracial. Mom’s white, dad’s black.”

“Thought I was picking up a little Creole vibe,” Ramon said, snapping his fingers to a tune only he could hear.

At once exoticized and overlooked by all around him—the story of Curtis’s life. “Don’t let them see who you are,” Miriam concludes before sending Curtis off to practice by watching famous film entrances of white stars. Amazingly, the plan works for a while, but the effect on Curtis is more degrading than triumphant. The swanky party makes for a wonderful comedic set piece, and what follows is even weirder. But Curtis’s coworkers, impressed as they might be, perceive only that miraculous suit (and the faint but undeniable strains of Professor Longhair), ending up none the wiser about the man inside.

This combination—dismissal and fascination—repeats itself in various guises throughout Among the Wild Mulattos. In “Ethnic Studies,” a pair of idiotic professors at a homogeneously white college subject four men of color to a grotesque parody of cultural interaction. In “The Lessons of Effacement,” a black man named Jerome has his life stolen by a mysterious double who looks nothing like him—not that any of his coworkers notice the difference. And in the title story, a biracial anthropologist finds a hidden clan of fellow mulattos who, tired of being despised by white and black alike, have founded a utopia of their own.

Williams’s prose is workmanlike and unflashy, a counterweight to the decidedly flashy subject matter. It serves him well, propelling the plot forward with clarity, keeping the focus on the characters and their extraordinary situations. He tends toward formality in syntax and word choice, and while it can sometimes feel a bit stiff, it helps get the point across. These are stories told by men trying to toe an impossible line: Afraid to eat fried chicken because it’s too black, afraid to like rock music because it’s too white. “Odder than two-headed calves, stranger than Uri Geller,” their every misstep is pounced on. We can believe that these lonely, disenfranchised men, caught between competing desires to fit in and distinguish themselves, would try almost anything to break the social restraints placed on them, but a flamboyant prose style really would strain credibility.

The tales Tom Williams has crafted in Among the Wild Mulattos offer complexity without forgetting to entertain, and beauty without sentiment. Like the writer sitting in a booth taking inspiration from fried chicken, this book has something unexpected, yet graceful and vital, to show the world.

About the Reviewer

Benjamin T. Miller is a writer whose fiction and essays have appeared in ZYZZYVA, Santa Monica Review, Epiphany, and others. He earned his MFA from UC–Irvine, and lives in Cambridge, MA. www.benmillerwriter.com