Book Review

There may be no more sane and logical art experience than reading a novel. The process invariably means following a linear pattern. We start at the beginning, read the first word, the first sentence, the first page, turn the page. Everything cascades from upper left to lower right. We want the characters and narrative to pull us through the prose like a lawnmower, systematically dispatching it row by row as we strive to get to the next chapter, the next part, the end. When we finish a book, we often grab another and experience it in exactly the same way.

There may be no more sane and logical art experience than reading a novel. The process invariably means following a linear pattern. We start at the beginning, read the first word, the first sentence, the first page, turn the page. Everything cascades from upper left to lower right. We want the characters and narrative to pull us through the prose like a lawnmower, systematically dispatching it row by row as we strive to get to the next chapter, the next part, the end. When we finish a book, we often grab another and experience it in exactly the same way.

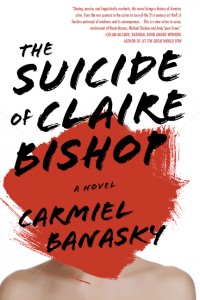

So, how does an author take this inherently rational activity and render a portrait of an unbalanced mind? That’s what Carmiel Banasky attempts—among other things—in her sparkling debut novel, The Suicide of Claire Bishop. In it, the titular character, a 1950s-era housewife, is aghast when a portrait painter includes imagery of Claire jumping to her death from a bridge in what is supposed to be a straightforward rendering. The painting lives on in 2004, when West, fringe character and schizophrenic, runs across it at a gallery and becomes convinced it was painted by his estranged ex-girlfriend. This obsession leads West to wean himself off his medication and engage in a quest to find his love’s whereabouts, a process that leads him to art thievery and, eventually, Claire.

One thing fiction does well is to metamorphose a prosaic quip into a line that staggers with insight, so devastating it makes you laugh. In Suicide, Banasky delivers such moments with uncommon skill. Take her description, from West’s point of view, of his brother-in-law Dan, a Hasidic Jew, a group West has become convinced is involved in a plot to capture his ex-girlfriend. “He has a spy’s eyes. His motives are beyond me. But he says that orthodox Jews don’t marry for love, they marry for respect and, without fail, love blooms from respect.” Maybe not what you’d want to hear on a first date, but the hard-won wisdom of the line is hard to miss. In other instances, Banasky is more openly humorous, like when West starts to skip pills and, in his obsession with the Hassidim, calls his sister Jules:

“Jules, quick, tell me how big the Hasidic population is.” I hope that Dan isn’t there but I’m afraid to ask in case he’s listening in.

“Hello to you, too.”

“How many people you think?”

“What? I have no idea.”

Calmly, slowly, I say, “Hello. Isn’t there a census number you know or something?”

“No one fills out the census. Are you all right?”

“Why don’t they fill out the census?”

“Because. We’re Jews. Bad things happen when you count us.”

It’s this kind of skewering from which Zadie Smith—and maybe Sarah Silverman—has made a career, and Banasky dispatches her zingers with an ease that feels like conversation.

West’s first-person narrative is only half of the book. The other half reveals Claire as she moves through her life up to 2004. I found Claire most compelling when she takes care of her mother, Elsa, who suffers from Alzheimer’s. Claire has encouraged Elsa to ready herself for a theater date with her husband, Ernest, who is long since dead. As Elsa stands at the window waiting for Ernest’s arrival, Banasky writes:

And Claire did nothing. She stood behind her mother, watching her wait, waiting for her to forget what she was waiting for. What had she done? Fairly pushed Elsa into the past and for what? To watch her wait for a dead man? When would it hurt less to be pulled back?

Banasky expertly marks Claire’s growth with in-scene encounters like this with the people she loves, pin-balling her to her destiny.

Banasky’s skillful telling runs ashore a bit as West continues his mental decline, especially in the scene that takes place in his childhood bedroom in Washington state. Here the prose keeps him—and Banasky—safely within its lines, prison-like. A writer could err the other way, as well, by making West’s point-of-view so crazy as to be unintelligible. Overall, though, it would have been more effective if Banasky had used less concrete prose to give West’s particular madness an untethered quality, one with more portent.

A few writers have successfully delivered—through the linear process of prose reading—a genuinely unhinged character. Quentin Compson, Humbert Humbert, and the narrator of “The Yellow Wallpaper” come to mind. For every writer that scores this elusive goal, several others wind up with renderings that—mirroring the form that reveals them—don’t quite shake the harness of rationality. While The Suicide of Claire Bishop might not boast a portrait of mental illness on par with these classics, it offers many of the other rewards of the novel form in spades—characters fraught with complication, a timeline epic in scope, and disparate points of view that both debunk and broaden the notion of truth.

About the Reviewer

Art Edwards's reviews have or will appear in Salon, Electric Literature, the Los Angeles Review, HTMLGIANT, the Collagist, Word Riot, JMWW, Entropy, elimae, Cigale Literary Magazine, the Rumpus, and the Nervous Breakdown. More at www.artedwards.com.