Book Review

Stephanie Sauer’s deftly written lyrical memoir, Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family, presents domestic violence, the legacy of trauma, art-making, and depression as part collage, part crazy quilt—asking us to rethink received ideas of the personal narrative. There is a huge range in this fascinating book, and while a conventional memoir might tie its threads neatly together, Sauer resists convention and instead enacts in her prose the expansive thinking and experience being described.

Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family sets itself up as an exploration of the legacy of domestic violence—the trauma of the abused and abusers. Organized in diary entries, each passage is prefaced with location and date. The book joggles between entries made in Rio de Janeiro and Nevada County, California, where her grandmother and parents are from. Sauer’s grandmother had an abusive husband, the trauma of which has haunted the family. He had served in WWII and returned with his own psychological wounds. As their granddaughter, Sauer explores how trauma is physically passed down through the generations, quoting scientific research that suggests that past traumatic experiences “leave molecular scars adhering to our DNA.” One’s experiences become so much a part of them that their “residue” can be inherited. This theme develops throughout the book as Sauer’s visual artwork of quilts, sewing, and installations act as a way to wear her grandmother’s trauma and exorcise it.

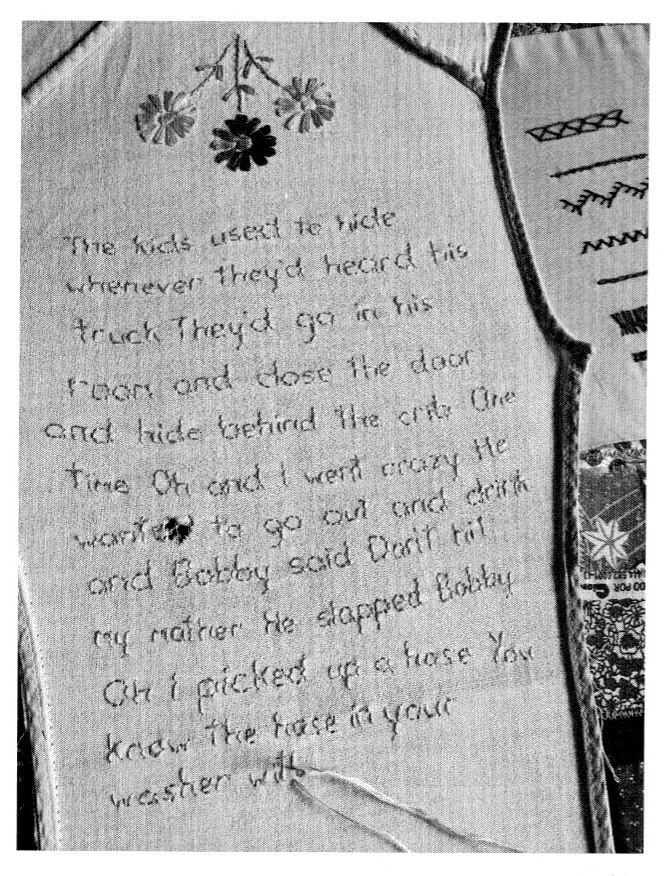

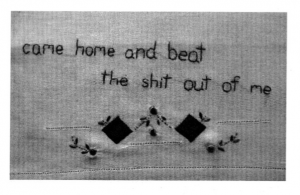

In her visual art practice, Sauer sews handkerchiefs with testimony from her grandmother’s experience. She sews “came home and beat the shit out of me” onto a handkerchief with delicate flower buds below.

Sympathy for the grandmother is the generator, but all women are invoked in this medium so directly associated with domesticity. One section reads:

The kids used to hide whenever they heard his truck They’d go in his room and close the door and hid behind the crib One time Oh and I went crazy He wanted to go out and drink and Bobby said Don’t hit my mother He slapped Bobby Oh I picked a hose You know the hose in your washer wi

The text is left unfinished, threads trailing out of the final incomplete word. Sewing is a cathartic entry point for an artist confronting this difficult family history.

Sprinkled with images of sewing, patterns, pages of other books, notes, receipts, Almonds Are Part of the Peach Family embraces its collage technique. At times the images flow directly from the prose, at times they feel arbitrary. At times Sauer is from Nevada County, at times Kentucky. At times her non-white ethic background seems foregrounded, at times she’s a “white woman.” The insecurity in this storytelling is key to its form and was one of the most satisfying lessons to take away from reading it. In an image from a book scribbled all over with underlines, highlighted words, excited asterisks, Sauer reveals the method behind her disjointed, diary-entry, lyrical prose. The passage cites academic Estelle Jelinek describing women’s autobiographical tradition as “episodic, anecdotal, non-chronological, and disjunctive,” with a “multidimensional, fragmented self-image.” Sauer’s writing is all of these things, and this purposeful, feminist embrace of women’s writing infuses every part of Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family. The diary entries are not chronological. Images are inserted and often distracting as our brains try to connect them with the surrounding prose. Anecdotes are shared and not analyzed, leaving that work to the reader. To read Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family is to be reminded that the construct of a linear, analytic memoir with a focused lens and chronological approach need not be the only way to write one.

I am taught by male example . . . not to point to a cultural past since such a gesture is to present oneself as unoriginal when the Western ideal of Art is originality. But there is nothing original about any of this human becoming. There is nothing original about the sequencing of words on a page, in the mouth. To deny these genealogies, to absorb them without honoring them first is an act of cowardice, a fragility I cannot respect. Far worse than cannibalism: parasitic.

Despite the disjunctive aspect of much of the book, Sauer does allow for some conclusions. The theme of mental illness caused by trauma returns as she considers the weight of a violent cultural past. Reading an article about a West African approach to mental illness, she reckons that “what we call an epidemic of mental illness in the West is just the clamoring of our unburied past.” An unburied past of trauma will haunt and Sauer’s writing itself has been a cathartic journey: “I consider my healing so far, the possibility that mine is not a broken story but a healing one.”

Almonds Are Members of the Peach Family resonates with anyone who has a troubled family history, for anyone who has felt she must take on a new identity for each new place she finds herself, for anyone who has felt the real or vague threat of violence in life or on the page—essentially, for any woman. But to say that this book is only for women is wrong. We are all finding out that the disjunctive, non-chronological, and anecdotal parts of being human are essential to how we convey our experiences, how we write our own lives. Leading by example, Sauer shows that not only can our stories can be messy, hard to pin down, transcendent, painful, healing, and provoking—the form in which we tell them can be too.

About the Reviewer

Emily Wolahan is a writer and teacher who lives in San Francisco. She is the author of the poetry collection HINGE (National Poetry Review Press, 2015). Her poetry has appeared in Boston Review, Georgia Review, Oversound, and many other publications. Her lyrical, historical essay, “The Direct Account of Frank Thomas,” won Arts & Letters's Unclassifiable Contest. Her essay "The Drawn Word / The Disappearing Act" is anthologized in Among Margins (Ricochet Editions, 2016). Other essays appear in The New Inquiry and Quarterly Conversation. She has won the Loraine Williams Poetry Prize and was runner up for the Drenka Willen Prize for Poetry in Translation. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and an MA in Literature from the University of Houston. She has received fellowships from the Headlands Center or the Arts and Vermont Studio Center.