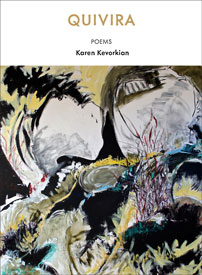

Book Review

The subtle revelations about history, land, culture, and grief in Karen Kevorkian’s third poetry collection, Quivira, are framed by movement: a passing coyote, “Against white snow the brown movement / absorbed by dark tangles of winter deadleaf,” a pilgrim’s journey beneath the “Andromeda galaxy old / sidelying universe,” a recounting of Kumeyaay practices, “for the pine nut harvest taking two days on burro and foot / up a shallow valley of silver sage and red shank,” traveling by car through an arid landscape, “On hwy 40 crossing Arizona / shallow volcanic cones . . . soft pink earth eroding from a cliffside / announces a mesa’s beginning.” Her descriptions, mostly unbound by punctuation and often shifting in time and place, are painterly and exact: “like starlings, small black birds / of gold eyes that with one mind rise . . . to block light then fan and turn / a pointillist demotic.” Quivira’s investigations of indigenous histories and the aftermath of Spanish colonialism are bound by the land formations, the human dwellings, and the species of the American Southwest.

The poems in the book’s title section, “Quivira”—after the “fabled Seven Cities of Cíbola”—document specific places littered with glimpses of the past and moments in the now. In “I Would Have to Think of Others’ Memories as My Own,” Kevorkian writes:

Pale green paloverdes feather Mojave

sideroads to Oatman, 130 miles to Needles

Land Sales, Yucca Proving Ground, gray boxcar

teeth strung across the despoplado

for we had not found

the kingdom, foothills dropped from pinched

fingertips mottled sky a blue and white.

We begin in the present—“sideroads,” “130 miles,” “gray boxcar”—and then somewhere after “boxcar” time shifts, without warning, to the past—“for we had not found / the kingdom, foothills dropped from pinched / fingertips.” Kevorkian continues, “they drew a line to keep us / from crossing over gave us headpieces / and dressed skins not gold and precious stones.” The speaker is now one of the Spanish “explorers” who is describing an encounter with the indigenous people of “Quivira”—an encounter that did not end in the Spanish acquisition of riches but likely resulted in the devastation of the indigenous peoples from violence or disease or displacement. Later we jump back to the present—“a good place to / batter down pueblos, looped aluminum / Xmas tinsel.” With these jumps in time and changes in speaker, Kevorkian melds the inescapable past to the ever-persistent present and creates an assemblage of the land and its inhabitants over centuries. She provides no exposition or explanation to guide us in these jumps and shifts; and so we must work for the meaning ourselves, making the discoveries that much more revealing and veracious in their overlapping complexity.

The book’s middle sequence, “21 Days,” is a pilgrimage through the “leftbehinds” and “the jigger of the present,” with ants, cats, leaves, stars, churches, religious artifacts, the color blue, light versus dark and truth versus lies as frequent motifs. She particularly emphasizes structures—roads, walls, fences, dwellings, and graves:

Cedar posts

and barbed wire bobwire

they called it

along the path

at intervals

rocks in disarray

a pattern that had meant

something, intention.

Both the cedar posts and the rocks could be at intervals. The line and lack of punctuation make it unclear. Their patterns had purpose once—the marking of property, fencing for animals, or, for the rocks, cairns for the dead or some spiritual motive. Similarly, we later come across “stones behind the morada” where “among each heap / a number painted on one stone / to number 14 the Stations // chamisa veering yellowish / and silver dust” and then “No / Trespass Tribal Lands No / Hunting No / Woodcutting such / are the given signs.” Kevorkian offers us these physical touchpoints from different histories that collide in the landscape, and her open form allows room for multiple interpretations to exist simultaneously. Stations of the cross merge into shrubs and dust and hills. The sign “No / Trespass Tribal Lands No” is bookended by no’s but is also broken by line between “no” and “trespass.” Perhaps the “tribal lands” have already been trespassed, “such / are the given signs.”

The poems—elegies, dramatic monologues, little portraits—in the final section, “The Call and the Drag,” feel more personal and mixed. In the elegy “A Voice Immediately Familiar,” Kevorkian begins, “Outside 7 a.m. the spiraldownward shrill, as if hawks spoke Mandarin / saying xie xie” and then:

usually nested in the green of the chinese elm

a name I am sure of, unlike the name

I can’t find for the hawk

its call not matching descriptions in Peterson

photographed from underneath, wings outstretched in flight

the bird would have to die for me to see that

my daughter, at her father’s, waits to name what is left

two turkey buzzards, yesterday

caped in long gray feathers, settling on the roof of his house

such a harbinger

too obvious, for his long dying that will surprise no one.

Word combining is a frequent device Kevorkian uses and one I particularly enjoy deciphering. Here “spiraldownward” grabs our attention because of its length in the line. It depicts the hawk’s movement and also describes her daughter’s father dying. The birds of prey in the poem are death symbols. When she writes “the bird would have to die for me to see that” the meaning is twofold: Naturalists used to shoot birds to identify them, and yet, what knowledge is gained by death from the one who dies and those who are left behind? The turkey vultures are too obvious as symbols, for they are carrion eaters, but they are there nonetheless, unrelenting, waiting. In her poems the coyotes, wolves, birds, and cats bring the weight of their archetypal characteristics with them.

Elsewhere in the book Kevorkian takes up the voice of a medicine man, “I cut open a breast with a stone knife,” questions artists or writers who appropriate others’ experiences, “in the local museum / plenty whiteguy views of pueblos . . . locals posed in costume / for Southern Pacific calendars,” grapples with politics, “Rescue boats wrap / migrant bodies / in gilt blankets / festive as chocolates,” and chronicles natural and man-made disasters, “largest release of / radioactive / material . . . still-high uranium / levels in Arizona / tap water.”

The collection is wonderfully complex in its work towards uncovering un-simplified truths within the near-constant framework of landscape and colonialism: “fantasies of Spanish stucco and red tile nod to / European slaughter over transsubstantive mysteries.”

About the Reviewer

Tracy Zeman's first book, Empire, recently won the New Measure Poetry Prize from Free Verse Editions. Her poems have appeared in Beloit Poetry Journal, Chicago Review, typo, and other journals. Her books reviews have been published in Kenyon Review Online and Colorado Review. Zeman has earned residencies from the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artist Residency, and The Wild. She lives outside Detroit, Michigan with her husband and daughter.