Book Review

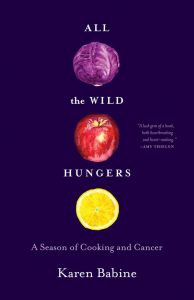

Karen Babine’s essay collection All the Wild Hungers will make you hungry, startle you with beauty, and break your heart. These sixty-four brief, carefully wrought essays center on the writer’s mother’s battle with cancer and on Babine’s use of cooking as a tool to cope. When her mother gets sick, Babine begins a delightful, quirky search to collect cookware—specifically colorful, vintage Le Creuset pieces that she gives names like Estelle and Agnes and Penelope Pumpkin. As her mother struggles with six months of chemotherapy, Babine uses her new cast iron companions to tackle increasingly challenging culinary feats, such as cacio e pepe, aebleskiver, and Julia Child’s boeuf bourguignon. But making these recipes is about more than mastery. The act of cooking emerges from a need for a center, for simplicity, for something to do, and for something to believe in.

Karen Babine’s essay collection All the Wild Hungers will make you hungry, startle you with beauty, and break your heart. These sixty-four brief, carefully wrought essays center on the writer’s mother’s battle with cancer and on Babine’s use of cooking as a tool to cope. When her mother gets sick, Babine begins a delightful, quirky search to collect cookware—specifically colorful, vintage Le Creuset pieces that she gives names like Estelle and Agnes and Penelope Pumpkin. As her mother struggles with six months of chemotherapy, Babine uses her new cast iron companions to tackle increasingly challenging culinary feats, such as cacio e pepe, aebleskiver, and Julia Child’s boeuf bourguignon. But making these recipes is about more than mastery. The act of cooking emerges from a need for a center, for simplicity, for something to do, and for something to believe in.

As the book progresses, we explore all the things that cooking can do, grounding oneself, during a chapter of illness in a family’s life. “On days like this, I need the physicality of cooking,” Babine tells us, “I need the tension of a spatula through cake batter, I need the action on the surface of a simmer, I need the chop. Days like these, I need to slow down, to take the hours required to make broth and stock, simmering mushrooms, Parmesan rinds, beef bones into something wonderful and useful because one cannot maintain . . . frustration and anger long term.”

Cooking also becomes faith at a time when the writer has none. She watches others lose their battles with cancer and thinks of what is happening to her mother and the vast unfairness of it. After the death of a friend’s wife, she writes: “I don’t believe in the Miracle of Modern Medicine either, because there’s blind faith in medicine, too, and that seems just as cruel and capricious as other belief systems. So I put my trust in Rose Levy Berenbaum’s The Cake Bible instead.”

Perhaps most importantly, food in this book becomes a vital mixture of memory, family, and traditions passed down through generations. “My mother remembers her mother standing in front of the stove in her slip and apron on a Sunday morning, browning a roast before they went to church,” Babine writes. Nor is cooking only for the women in the family as she recalls: “We used to call my grandfather Kermit the Pancake King. . . . My grandfather’s griddle of choice was electric, as is the griddle we bought for my father as we crowned him the new Pancake King after my grandfather died.”

Particularly endearing are the stories of aunthood Babine weaves into these pages as she creates new traditions with her niece and nephew. She has a close relationship with her sister’s children, and she cooks with them often, “not just because it’s fun,” but because “I am working to create new historical memories with my niece and nephew, writing the new food history of our family.” The reflections on the author’s solo life and the joy she finds in being an aunt are moving. She takes being a “PANK”—Professional Aunt, No Kids—seriously, lamenting the loss of the children’s baby-speech as they grow up. It is refreshing to see the elevation of aunthood in these pages and its recognition as a meaningful role. The writer’s sister is pregnant with her third child, and this pregnancy, growing within her, serves as a parallel to the cancer growing in their mother. Babine reflects on these contrasting developments—one bringing potential life, the other potential death—both harbored within the body.

All of this makes it sound like perhaps a somber text, one too heavy with the gravity of the mother’s situation to be enjoyable—yet in Babine’s writing, the reader finds moments of startling joy baked into this whole journey. The descriptions of pancake-flipping and crust-making are delightful, and the reflections on food and family are evocative and heartening. As many of us do, the writer sees a sense of herself in the foods her family eats, dishes specific to her Swedish roots and Minnesotan culture: “In summer, approaching Midsommar Dag, we dig tender, tiny new potatoes from the garden, boil them whole, then put them back in the pot with milk and butter, and serve those red potatoes swimming in rich whiteness that glimmers with butter fat. Mjölk och potatis. In summer, we feast on color, cucumbers in salt water, corn on the cob, red potatoes, tomatoes sliced thick.”

On a craft level, the work is skillful and gorgeous in its simplicity. Babine’s pieces often have the feel of prose poetry, giving us lines we can almost feel and touch. In one description she illustrates perfectly the power of comfort food: “I find delight in the fat from the melting cheese having woven itself into lacelike bubbles on the surface, slightly darker than the golden broth, and eating my feelings seems healthy and desirable, the movement back into murmurs of pumpkin and honey as my small nephew fights against sleep in my arms.”

In the end, the gravity of the battle her mother wages in these pages is balanced by the levity of the writing, and by something sturdier—the link of generations and the tight-knit bonds of tribe. This is a book for those who love language, for those who love cooking, and for those who want a new way to meditate and to purposefully slow down. The linked essays tell a meandering story, examining life along the way. There are reflections on motherhood and the choice not to have children of one’s own, as well as discussions of the dismissal of women’s pain and the sexism still pervasive in healthcare today. There are also portraits of place in vivid descriptions of Minnesota hot dish, Christmas Eve carols, and church suppers. To read Babine’s essays is to walk a while with a family, get to know their roots, and come out nourished in every sense of the word.

About the Reviewer

Emily Heiden’s writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Brevity Magazine, the Hartford Courant, and Literary Hub, among others. She holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from George Mason University and is pursuing a doctorate in creative writing and literature at the University of Cincinnati. Follow her on Twitter @_Emily_Heiden_