About the Feature

[hear the author read this piece by clicking this link.]

Their hosts in the south of France, the Clayburns, had asked Roger and his wife not to bring the babies with them. But Malcolm was only two-and-a-half, and Travis just six months. Roger and Claire felt they didn’t have much choice. Or Claire felt that way. Roger didn’t quite know what to think lately, buffeted as he’d been by Claire’s erratic moods. Rages. They weren’t connected to anything rational or predictable, and they had come on because she’d acquired an illness after having baby Travis. Graves’ disease. An incurable autoimmune disorder that launched antibodies at her thyroid, messing up her metabolism and her ability to think.

So she was skinny and crazy.

“Thomas and Jane are going to freak,” Claire said as they collected their baggage at the airport in Nice. Roger nodded. They surely would, but he didn’t want to talk about it.

“Maybe they’ll understand,” she said.

Roger pulled one of their bags from the conveyor. Oversized, of course. A sharp stitch ran up the side of his body as he lifted the ten-ton beast. Another thing to try to fit into the car they’d reserved for the windy, thirty-mile trip from Nice to the village. Roger was leading a course on genealogy again; he’d taught here two years ago, part of the cultural, diy programming the Clayburns loved to “curate” for their wealthy expatriate friends. “Like the salons put on by Gertrude Stein, only with better wine,” Thomas had joked when he initially contacted Roger.

Roger had hesitated when Thomas called about reprising the class—they’d just had Travis—but Thomas said Jane and her friends were clamoring for it. They would up his fee and cover his airfare. And they would put him and Claire up in their luxurious rental flat overlooking the rocky hillsides that slanted down to the Mediterranean. Like last time, they would be treated like royalty. As repayment, Roger would betray his hosts by bringing the babies when they’d specifically asked him not to. There had been other betrayals, too, but he would not stop to think about those now.

In the rental lot, Roger stared at a car not much larger than the plastic one Malcolm pedaled around their tiny backyard. The luggage would not fit in the trunk. Seeing their predicament, the lot attendant hurried over. “You upgrade to this.” He pointed to a minivan. Oh, Christ. A minivan! But Roger assented and soon they were strapped into a boxy Renault outfitted with two rental car seats that were far from regulation, but Roger frankly didn’t care.

Claire read the directions aloud from the passenger seat as Travis fussed in the back. Neither child had so much as closed an eye the entire trip from Denver to Frankfurt to Nice, not even the baby—a feat of wakefulness Roger hadn’t thought possible.

“There’s a difference between people who have kids and those who don’t,” Claire said. “Jane doesn’t understand. And Thomas forgets, since his are all grown.”

Roger decided not to engage. Jane embodied an unforgivable combination of wealth, refinement, and stunning beauty, and Claire, who underestimated herself as merely pretty, took regular jabs at her. The digs were worse now, as everything was.

“They’re just worried about lawsuits,” Claire continued. “They think Malcolm will climb up on the windowsill and fall from the flat or something. We’ll write up a waiver. That’s what we’ll do.”

Roger focused on the landscape, unbelievably blue vistas of sea with a ring of white sand along its shores. Out the other window, rolling hills patched with orchards and vineyards. Soon they turned off the main highway and began the slow ascent to the village. Last time they were here, Thomas informed them that October was brush-burning season in these hills and, true enough, a smoky scent permeated through the open windows of the minivan. The road braided into the hills in sharp Ss, and at every blind curve Roger worried they would meet another car head-on. But so far luck was with him. Passing the nestled towns that had always drawn the rich and artistic—the Picassos and Renoirs—Roger felt a boost, a subtle, sexual stirring.

“Oh my god!” she shrieked. “Did we bring my pump?”

He was sure they’d brought the pump. “I think so, but so what if we didn’t? You’ve got the man himself.”

As if on cue, Travis made a gurgling sound and they all chuckled together. Thank god. In his head, Roger reviewed the trip’s itinerary—a welcome hors d’oeuvres party at Jane and Thomas’s house tomorrow, where he would meet his twelve students, a preliminary seminar the next morning, and then three days of class. He’d lugged along two boxes of books and handouts; he was eager to be rid of them so that at least something about their return trip would be easier.

Roger had taught history to high schoolers before branching out on his own. He remembered, five years ago, gathering the courage to leave the school by ordering business cards with the cheesy tagline “Roger That! Genealogy: Your family is my business.” Now he saw that Your x is our business tagline everywhere, but he had been young—a young thirty-one—and thought all of his ideas were original. Claire, two years younger, was the primary breadwinner when he quit teaching to build his business.

“Over there,” Claire said. “That’s the turn.”

“I think it’s the next one, honey.” A casual tone was critical.

“Are you sure?”

“I’m pretty sure,” he said, although he was certain.

He followed the maze-like turns until he saw the arrow to the village. They had to stop at Thomas and Jane’s to pick up the keys to the flat, and this would be the reckoning. He imagined Jane’s eyes, which were always darkened in a way that made him think of Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra. News of the kids would likely disrupt any chance he might have to steal away with her.

“I can’t believe we’re back.” Claire sighed happily. The creases between her eyebrows were gone, and she looked almost like she’d looked pre-derangement, except that the whites of her eyes were gigantic, constantly surprised—a product of the Graves’.

“Believe it!” Roger said. They drove up one of the steep hills that backed to the Clayburn estate; Thomas and Jane had bought a medieval stable and transformed it into something out of Architectural Digest. Stone walls, wood floors, built-in wine cellars, and a spiral staircase that led up to lofty rooms. Last time, Roger had entered the upstairs rooms only once, when Thomas had an appointment and Claire was asleep in the flat with Malcolm. He remembered the bed took up half of the room. In Jane’s passion she’d stripped off all but the fitted sheet, and afterward the linen curtains rippled with the breeze and lapped at their bare toes.

He left his family in the car and walked up to the low, stone courtyard that fronted the Clayburns’ home. The arched door was restored from the 1600s. At eye level, an open knot in the wood resembled a face in profile; the door gave off the illusion that it was breathing.

He knocked and Jane opened it within seconds. Cleopatra. She looked even prettier than she had two years ago. She had straight, shiny brown hair that he remembered as the purest black. A crooked smile crossed her lips, and then she turned to call Thomas.

“Hey, stranger!” Thomas lumbered toward them from the recessed reading room, his index finger stuck in a thick hardcover, his big face filled with genuine happiness at seeing Roger. “Where’s your gorgeous wife?”

“Thomas! Good to see you, my man,” Roger said. They shook hands, and Roger and Jane kissed each other on the cheek, then he stood while they both stared at him, waiting for his answer.

“You see,” he said, “I know this is going to surprise you, and not in a good way, but she’s in the car. With Travis and Malcolm.”

Jane and Thomas looked at him, neither saying a word. Then they looked at each other. He felt a moral chill. This was a long way to come to spring this on them.

“Well,” Jane said, her eyes cold. “I guess you really did it, then.”

Thomas looked less shaken, but Roger knew that Jane’s disapproval weighed heavily on him. Jane and Thomas had met just five years ago. They were still newlyweds of a kind, and Thomas was much older than Jane—in his fifties, while she was just in her early forties. He needed to work extra hard to keep her happy.

“Let’s not worry about it, okay, Jane?” Thomas said.

“I know you’re concerned about the window, so we’ll sign a waiver,” Roger said, remembering Claire’s idea. “Do you have one? Because if you don’t, I can write one up.”

Thomas walked to the kitchen, opened a drawer, and came back with a set of keys. “Don’t worry about it, okay, Roger? Could we not worry about it, Jane?”

Jane agreed, so long as Roger was watchful of the low, screenless living room window that overlooked a courtyard, forty feet below. The keys were handed off, and the entire encounter was blissfully over. For now.

When Roger got back to the van, Claire was frenzied. The baby had woken up. Malcolm had kicked him in the head (“An accident!”), and there was no help—no help!—and she hadn’t slept for so long, and all of it just seemed so hard. Why did it have to be so hard? Why?

“I don’t know, honey,” Roger said. “I don’t know.”

Prior to being a pricey rental, the flat had been used by Jane and Thomas; they had lived here while watching over the stable renovations. The door opened to a gorgeous, hideaway kitchen that hummed behind complicated cabinetry. In front was an island with a basket filled with fruit, wine, and cheese, a vase of freshly cut flowers. Jane’s touch. Then, as you entered, a wall of windows took over; out of these wood-shuttered windows you could glimpse hazy valleys and red-tiled roofs all the way down to the Mediterranean. Utterly breathtaking. Two bedrooms off one side of the kitchen, and then the master bedroom, sharing the same view as the living room. Claire and Roger dropped their bags, put the baby in his carrier and Malcolm on the floor, and hugged each other.

“I’m sorry, baby,” Roger said. “It’s been hard, but this will be great, you’ll see.”

“Me too,” she said into his neck. “I love it here. I’m sorry, too.”

That was it. He wouldn’t start things up again with Jane. No sneaking away from the seminar to have a quick tryst in the bathroom; no tiptoeing up to her house in the middle of the night to throw a rock at her window and meet her in the alley behind the five-star restaurant. No trekking up there to ask for something like detergent or sunscreen for the kids, getting a quickie in, and then returning with the soap or lotion as an alibi. No. He wouldn’t. He was a better man than that.

“Honey,” Claire said, smiling. “Are you getting frisky?”

“I always am for you,” he said, and Claire smiled in a genuine way.

He laughed bashfully. Their sex life had fallen off since Travis was born, naturally, just like when Malcolm was a baby. But last time there was no disease impeding their progress back to the new normal.

Roger went to retrieve the rest of their luggage from the van. When he returned, Malcolm was climbing on the couch facing the tall windows in the living room, and the baby began to titter and kick. Roger clapped his hands and went to work. They’d brought a portable crib that fit, through a marvel of product engineering, into a duffel bag. He took it into the bedroom to assemble it.

“Maybe we shouldn’t,” Claire said. Then she thought for a second. “No, I guess we have to.” She meant have the baby in their bedroom. By the middle of each night, the baby would be out of the crib sleeping between Claire and Roger, the baby’s mouth suctioned to Claire’s breast. In the morning her nipple would be elongated and wide at the tip, especially if Travis kept his grip all night, which he miraculously did from time to time. Roger thought of it as Travis’s way of tagging his territory: This is mine. Stay away. It’s for me. And who could blame him?

That night, Roger spent some time trying to get his head around the curriculum. On the first day he always wowed them with his philosophical line of inquiry: Why does it matter? Who cares about our ancestors, our forebears, our past? It matters because it creates meaning for us here on earth. He paced the room in his boxers and a T-shirt, barefoot on the cool tiles, and ran through stories he’d tell of people finding their families in the direst of circumstances. One man found his biological great-uncle, who, having outlived the rest of his family, was alone on his deathbed. His nephew arrived just in time to take his hand.

Every photograph you have is a clue. Primary sources are the holy grail: Every letter. Birth certificate. Death certificate. Family Bible, of course, and journal. For secondary efforts you might log onto the census data commercial sites, check birth and death records online, scan newspaper archives and online forums. Hardcore genealogists could turn to DNA testing and extreme measures, but that seemed so impersonal to Roger. No, he enjoyed telling his own story, encountering an original source that had inspired him to leave teaching and start Roger That! He’d gone to northern Michigan to help his mother clean out her parents’ old barn, and in the musty confines of its attic, she’d held out a bundle of letters to him. The envelopes, stiff with age, were covered with the most opulent handwriting he’d ever seen. They were written by his great-great-grandfather Roger to his wife, Alicia, during the year he was off fighting in the Civil War. “It’s my pleasure, dear Alicia, to address a few lines to let you know that I am in good health,” they started. Holding the letters, Roger had felt something new—a tenderness and gratitude that started with the bundle in his hand, traveled up his arm and across the surface of his skin, but finally burrowed down into him. It was a sensation he hadn’t known he was missing, and he’d felt a shock at its being granted to him. Something he didn’t have to earn. Had his great-great-grandfather not survived the war, his mother was saying, she would not exist, Roger would not exist. Nor would Malcolm or Travis, now, and that thought made the space behind his navel pull and ache.

For weeks after reading the letters, Roger’s life felt richer. It was as if he were glimpsing strangers through honeyed light—the tenth grader in his world history class who used to drive him crazy with his ceaseless banter was suddenly beautiful. The grumpy vice-principal whose toad-like visage was one of the few Roger ever found abhorrently ugly—suddenly he felt glad to see him and told him so. Genealogy is a map to your heart, Roger would say to his students. It makes you naturally kinder, lured into the shared space of our humanity. To uncover such personal history is the most powerful feeling in the world.

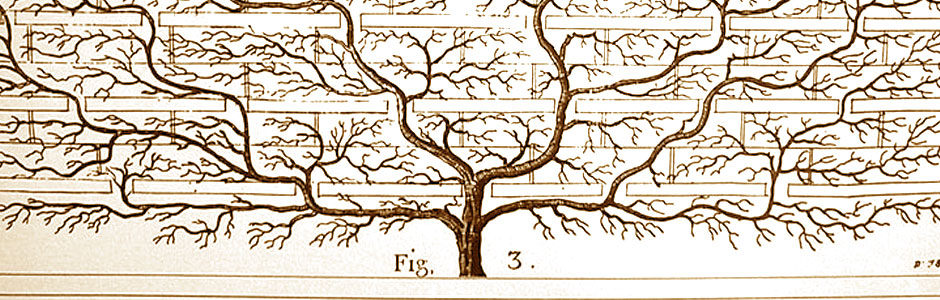

France provided heightened atmospherics. Here history mattered, evident in the architecture, the landscape, the literature. Look at the Clayburns’ own house! Ancient and meaningful. America was not like that, and suburban America, where he’d grown up, even less so. As the course marched on, he’d hand out pedigree charts. They’d perform mock interviews. He and Thomas would set up multiple computers with wireless Internet and people would log into databases. Some of the participants would cry. Some would be in shock. Others would be touched, seemingly for the first time, by their own larger stories. He knew that people would always be happy with his product, because his product was their lives, getting in touch with their lives. It was magical. A guaranteed smash hit.

The night of the welcome hors d’oeuvres was touchy. Roger knew that he and Claire would be straining good will to show up to the party with the children. At the same time, the boys obviously could not be left alone.

“I’m not staying here,” Claire said. “You can stay here if you like, or we can trade off, but I am not going to sit in an apartment in France while you’re off with the Clayburns sipping the best wine and eating foie gras. It’s just not happening, so let’s not talk as if it’s happening.”

So they both got ready, almost as if they were playing a game of chicken. Obviously he had to attend—he was the reason for the party. Some of the students were returning from last time, but about half of them were brand-new. This would be their chance to meet him and one another, so they could feel at ease once things really kicked off.

Roger adjusted his tie—sadly, this was an occasion for a tie—and Claire ironed her hair flat and put on what seemed to be a smidge too much makeup. She was more beautiful the less she wore; she knew he felt that way, so sometimes he took her caked-on look as a deliberate act of rebellion. With what cause? The question implied there was one, and there never seemed to be.

She wore a full-length, tight-fitting dress. Her stomach was completely flat; her arms downright skinny, her formerly ample backside now a miniature version of itself. She was at least fifteen pounds lighter than usual—something her doctor was trying to address with little white pills she frequently skipped taking, claiming they made her too tired.

“Okay,” he said, standing next to her at the mirror. Her long blonde hair gave her a tan, movie-star look. “So we’re all going?”

“We’re all going,” she said, concentrating on her mascara tube. She shoved the wand in and out vigorously. She was on her third coat. “And if you have anything more to say about it, why don’t you just say it instead of asking me questions? Why don’t you make a statement?”

“Here’s my statement,” he said. “Let’s go.”

The party spilled out onto the front stone patio, illuminated with flickering gas lanterns in the early dusk. When they entered through the gate, Jane approached Claire with her arms outstretched. She cooed at baby Travis, patted Malcolm on the head like a dog. At one point, when Claire turned to hug Thomas, Roger saw Jane’s eyes rake over Claire’s body, measuring its new contours.

“We’re so glad you made it, lovely Claire,” Thomas said, kissing her joyfully on the cheek. He widened his stance, which was already wide, because he was wide, and pivoted out to show Claire that another party guest, an American expat, had a baby—adopted from China! She sat in the dark at the far end of the patio, trying to coerce the baby to eat. Thomas called over to her, introducing Claire, and Sally smiled, waved.

Claire went with the boys to sit by Sally, and the two women were quickly engaged in conversation. Malcolm took a seat next to his mother and began to eat cubes of cheese, and Roger moved into the house feeling lighter than he’d felt in days.

The recessed reading room was overflowing. Three new students introduced themselves. A fifty-something Indian woman named Gita and a pair of English sisters—young to show an interest in the topic. Both seemed to be in their late twenties, and one was pregnant. He also greeted four others, local expatriates from Australia, Ireland, and America, whom he had met last time. He gave them his standard: “Are you ready for this? It’s going to be an adventure; that much I guarantee.” Everyone was eager. They began telling him what they already knew. This had been their homework: Interview the oldest living members of your immediate family. That is, grandparents, if you have them; parents, if you have them; then move out to aunts, uncles, siblings, cousins, and the like.

Gita pulled him aside. “I hear nothing but good things about your seminars from Jane,” she said. “She’s actually quite fanatical about them.”

Something about the confidential way she said this worried him. Perhaps Jane had told her about their fling, and it had given her ideas. Not that he was such a catch; just that he was novel. Not bad looking, sure—he still had his hair and wore the same 34s he’d worn for eons—but the most important thing, he suspected, about Jane’s attraction to him was that she’d never have to see him again. Maybe ever. And the feeling was mutual. He wouldn’t have pursued his attraction to her had she not, two years ago, pulled him into the washroom after cocktails, her fingernails painted deep red, her long-boned hand groping the wall to turn off the light.

Claire wandered into the house with the baby, Malcolm at her heels. He appeared to have been crying, and Roger knew what that meant.

“You’ll have to excuse me,” he said, smiling at Gita’s skeptically pursed mouth. “It seems I’m needed to handle the newest buds on our family tree.” He willed a glimmer to his eye, and she smiled in response, maybe devilishly, as he walked over to his wife.

The rest of the party was a blur of obligation and flirtation. After what Gita had said to him, he felt called to act the part. In truth, he was one of the more monogamous men he’d ever known. He’d cheated on Claire only once, with Jane, during their sexual dry spell after Malcolm was born. Add to that the reality of becoming a parent—sincerely shocking—and the lure of the village itself. The air here carried something intoxicating along with the wood smoke, and in its haze he felt different, like someone on vacation from his real life.

“Roger.” Jane approached him from the other side of a plate of triangular caviar toasts. “Did you find the flat satisfactory?”

He assured her that he had. Claire had gone back outside, once again exiled with the other mother and baby, and he now held Malcolm on his hip, but Malcolm began squirming and kicking his legs, a scene that Jane watched with a mixture of horror and bewilderment. Placing him down, Roger grabbed a toast and popped it in his mouth.

“Good,” she said. “Now I can lord something over you.” She winked, leaned forward as if she would brush his lapel, but stuck something in there, a note, and moved on to the other guests. He watched her walk away, the black dress hugging the tininess of her waist, the amplitude of her curves. She was an earlobe biter and a screamer and a dirty talker.

Roger swallowed the caviar—oily with a subtle brackish aftertaste—and turned to see Malcolm standing, tiptoed, at the Clayburns’ antique buffet. His fat little hand reached for a glass oil candle, and Roger lunged to sweep him back up in his arms. He needed to get out of here. Since Claire got sick, he’d become everything—the breadwinner, the primary parent, the doting spouse, and the one with the keys to the insane asylum. In moments of self-pity, he saw himself as a besieged figure, an average guy weighed down by diaper bags, car manuals, dishes to wash, classes to teach, personal consultations to deliver, and a wife to please. The problem with the last part was there was no way to know what she wanted until it burst out of her with a certain velocity.

“I just can’t do this anymore,” she had yelled at him months ago, when they still didn’t know what was wrong with her. “You know? I just hate my life. I can’t do it anymore.”

“You hate your life,” he’d repeated.

“Yes. It’s a stupid life. Who ever thought it would be so . . .”

He waited.

“Senseless,” she said.

The baby had had a blowout—poop spilling from his diaper up his back and down his legs—the second time that night. After the first time, she’d given him a bath, changed his sheets, put him in new pajamas, replaced all his blankets. When she put him back in the crib, the entire thing happened again. So she was angry at Roger for having had an easier turn the previous night. Angry at the baby for having multiple blowouts. Angry at the universe for what she didn’t realize at the time were antibodies firing at her thyroid, causing it to swell and overact and rob her of sleep and moderation.

“You want me to go change him this time,” Roger had said, irritated. “You think it’s not fair that you got stuck with this night, even though I’ve had tough nights in the past and you didn’t offer to take over for me.”

“You don’t understand.”

“I’m sure I don’t. Do you?”

She’d started crying. She picked up the new package of diapers, the next size up, and when she couldn’t get them opened, she kicked the entire package against the back wall. “I fucking hate this!” she yelled.

Roger picked up the package of diapers and ran upstairs to do the changing. He couldn’t believe how quickly things had devolved. Now they were kicking diapers against walls. That was where they were in their happy little lives.

It wasn’t long after that he’d insisted she go to the doctor to check out her constant shaking and sleeplessness. Weight was falling off of her. The doctor at first thought she needed to eat better, and that was believable. She’d developed a terrible diet. Needing more calories for nursing, she had moved to mochas instead of lattes, whipped cream instead of foam. She’d added cheese to everything, and still: shaky, skinny, moody. He’d wondered if this was simply the new Claire.

Now, after the diagnosis and the occasional beta-blocker, the rages were accompanied by a certain fatalism. She was convinced that she was doomed, and Roger’s job was to dissuade her from this conviction. When they got home from France, she was supposed to nuke her thyroid—swallow radioactive iodine that the gland would take up suicidally. He badly wanted her to follow the doctor’s advice, but she wouldn’t hear of it. Part of the reason they were on this trip was for her to prove she was okay: See, we can still go to Europe, even with the disease! We can be the family that travels with small children to Europe, even with Graves’ and no savings account, and everyone enjoys it and takes lots of pictures and eats out and it’s the absolute mofo American dream. Got it?

When they left the party, Claire and Roger were pretty drunk. Roger read Malcolm a book and put him to bed, and when he came to his room, the baby was asleep in the crib and Claire was taking off her clothes. She appeared angry and unsteady.

“Did you notice anything weird about Jane?” she said.

Roger’s forearms tensed as he loosened his tie. “Weird, how?”

Claire was wearing her black bra and panties, and Roger noted them. She yanked off her earrings with a habitual force. “She kept staring at me, and then she said something really rude.”

To hide his face, Roger turned and hung up his jacket. “What did she say?”

Claire stood in front of the mirror, wiping off her eye makeup with cotton balls doused in blue liquid. “She said, ‘It must be hard sharing your husband with so many women; don’t you get jealous?’ And I didn’t have the heart to tell her that all the women were old like she is or even older. God, I’m so not worried about it, but her saying it really kills me. She must have a crush on you or something.”

Roger let out too loud a snort. “Oh, come on!” He was giving it all away. “She’s just making small talk.” Inwardly, he fumed. What the hell was Jane doing? Did she so resent their bringing the babies that she was willing to toy with his marriage? Roger imagined lesser, weaker men being defined by infidelity. He had convincingly deferred it. The trysts from two years ago were something to be thought about only, if at all, when he needed to muster passion during a lull in his lovemaking with Claire. Roger walked through the grocery store, the library, the daycare feeling not like an adulterer, but like a man burdened by other, more trivial worries. And here was the miracle of it: the world, Claire, Roger himself, everyone had let him do this. It was as if the universe had granted him a trove of absolution, and by coming here, by coming back to the scene of the crime, he was trying to give back that gift. He was almost begging to return it.

The thought paralyzed him; this trip was the height of foolishness.

Roger couldn’t even think of losing Claire. He’d always loved her with the same immoderation she showed, ironically, now. He’d been the one to pursue her when they both taught at the same school. In the hallway one day, he asked if she’d like dinner and she said, “If you promise not to make me laugh. I have a history of choking.” They’d gone to a rib place and she’d told him her life story and he’d fallen in love. She ran half-marathons, grew tomatoes in her garden, and did complex math in her head. Plus, she was a knockout.

Even two years ago, with Jane, he’d known the affair was just a hiccup in his life, a desirable life, mostly because Claire was in it.

They went to bed without making love. Roger had locked himself in the bathroom to read Jane’s note, asking if he’d meet her in one of the rooms at the auberge after the first class. I’m not as strong as I look, she’d written in the note. I need this. He softened toward her a bit and wondered what was wrong. The baby was asleep next to Claire, who managed to cradle him in her arms even in sleep, and Roger heard the telltale sound at the door—footsteps, then the doorknob turning. For the second night in a row, Malcolm was coming into their room at two thirty in the morning. Roger leapt from the bed, ushered Malcolm back into the living room, and closed the door gently behind them.

“Hey, little man,” he said, trying to focus his eyes. “See how dark it is outside? That’s because it’s the middle of the night.”

“Yay!” Malcolm said, throwing his arms in the air. “Middle of the night!”

He had not adjusted to the time difference. Roger was starting to doubt that he would. Malcolm took his father’s hand and pulled him toward the couch. Since the baby was born, Malcolm and Roger had become closer. Now Malcolm came to Roger when he was sad or needy or even joyful, and although he wasn’t yet as verbal as some two-and-a-half-year-olds, he broke Roger’s heart when he’d said, looking at Claire and Travis, “Mommy has a new baby.”

Malcolm let go of Roger’s hand but then grabbed it back. First he paused to lick his little pink lips, then he kissed the hand on its wide flat back. This was a new thing he did, now that Roger and Malcolm were a team. The gesture filled Roger with a love that ached in his midsection, and he lifted Malcolm into his arms and squeezed him, nuzzling his neck until Malcolm’s giggles threatened to wake Claire and Travis.

Roger set up his laptop to play a Disney movie that he’d brought. This was going to be absolute agony. Why, again, had they decided to come? Oh, that’s right. It was their American dream to be world travelers with babies.

As the sunrise began to streak the horizon, Roger stood up from the chair he’d been dozing in and turned to see the movie was long over and that Malcolm was asleep, his tiny mouth gaped open on the silk pillow that had been placed nattily on the yellow couch. Everything was pristine. No wonder they didn’t want children here. He found a throw blanket and covered his son with it.

He thought to move into the bedroom to get some sleep, but it was too late. If he fell asleep now, he’d be mid-rem when it was time for his opening remarks meant to inspire the group about the journey ahead. He prepared mentally for the fact that his eyes would likely ache all day; he’d have that punchy, unhinged feeling during discussion, which actually sometimes worked in his favor. People who laugh during seminars end up enjoying them.

“You’re up early,” Claire said quietly, emerging from their room with the baby.

Roger thought of the torture that made up the last two nights and almost said something about it to Claire, but it didn’t matter. He would get no special credit. “Yeah, our little guy was up and ready for life at two thirty.”

“Oh, god,” she said. “I’m so sorry. I slept terribly, too.”

He raised a hand, swooped in to grab the baby from her. Travis’s face broke into a pudgy smile. Claire covered her mouth, and when she removed her hand, she too was smiling. Glowing like she used to glow.

Maybe she was getting better.

He left the flat in good spirits despite the lousy sleep. When he finished teaching, he’d go back to the flat and Claire would be exhausted, ready for him to take over, so he’d go from work to a different kind of work, all without the benefit of their home, their routines, the kids’ toys, the network of family and babysitters they had back in Denver. But it was okay. As he walked down the cobblestone path to the center of town, he passed the boulangerie and its aroma of fresh croissants, the fruit stand whose doors and windows were thrown open, and the Place du Puits, filled with townspeople and tourists sitting at the metal tables, drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes.

The air was warming when he made the turn down to the hotel where most of the students were staying, an auberge with an airy little atrium in which he’d be running classes. What was Jane thinking—suggesting they meet here? His earlobes tingled at the thought. When he walked into the dark-paneled building, the owner, Jean-Paul, said something briskly in French to him, and he responded in something that was a hybrid of French and Spanish, and Jean-Paul shifted gears. “Okay,” he said. “Please, we will come in with the lunch at noon, with the trays.”

“Yes,” Roger said, too tired to fake French. “Yes, noon would be great.”

He walked into the atrium, which held all the light in the world, and checked the setup. Everything looked great. A large seminar table. And, as he’d requested, white paper hung from the wall near his chair; he flipped it up—there were more pages underneath. He should be all set for the session. He had his handouts. His first questions (“What do you already know about your family? Write it.”), his first points for discussion (“What do you imagine are the absolute best sources for amateur genealogists—either commercial or standard?”), his first anecdotes, like the one about the red-headed man who discovered the source of his curly hair—a grandmother who was part Jamaican!

All of it was ready, and it was in Roger. He thought of Claire calling her life “senseless.” Wrong. His great-great-grandfather, fighting off Confederates and a bout of the measles (“it is a nasty mean disease, dear Alicia”), he’s the one who gave the redhead his Jamaican grandmother. Roger was part of a legacy—every person was—and no one could think their life senseless if they understood it as part of the grand narrative. Yet Roger knew too many people who had no moorings, no religion, no philosophy, nothing. Their emptiness terrified him.

“Am I the first one here?” Gita walked in like a woman who was used to being watched as she entered a room.

“You are first,” he said. “And foremost.”

“Wonderful,” she responded. “Where are you sitting?”

He pointed to his materials, and she took a seat a couple chairs away from him, which put him at ease. The rest of the group trickled in, one at a time, and finally, at the stroke of ten, Thomas and Jane arrived, all smiles and Hello, hello! and Did you find the book I mentioned? Everyone helped themselves to coffee or tea. Roger cleared his throat. It was time to get started, and Jane looked up, narrowed her eyes at him, and then sat, disturbingly, right next to him. Thomas chose a seat between Gita and the pregnant Englishwoman.

They all gave what Roger called their “elevator intro.” This was intended to frame, for themselves and others, who they were, why they were here, and one interesting fact they already knew about their family. Gita said that her family in Bombay had always found her amusing, living in the south of France, marrying an Englishman. The English sisters had grown up in a castle that became famous because one of the Beatles married there. Sally went next, talking about adopting a Chinese baby in France, then came intros from several of the returning folks, and the whole while Roger was thinking about Jane’s neck, the way it elongated when she was on top of him.

Thomas coughed. He said he already knew everyone so he would be brief. He was interested in finding out more about his father’s family. His father had died when Thomas was very young, yet his paternal grandparents were the ones who’d put him through Yale, all anonymously and from a distance. He hadn’t learned of it until his mother told him, just before she died. His successes in life, he conceded, were in a material sense quite vast, and he could trace them back to the ghost-presence of his father. He was a little choked up by the end of his speech, and when Roger looked around, so were a lot of the people there. They all seemed to genuinely love Thomas. Made sense—he was garrulous, friendly, interested in other people. Jane’s only complaint about him, she’d confessed two years ago as they caught their breath near the rushes behind Le Chateau, was that he was overweight and boring as sand.

Now Jane was up. “You all know me,” she said, reddening a bit, despite her usual savoir faire. She looked down while she talked, tracing designs on the table. In this light, Roger could see the etched lines around her eyes and mouth that makeup and evening hues could camouflage. He didn’t mind the lines and felt they worked in counterpoint to her large, blue, cold interior. “I’m here because I didn’t get as far as I wanted to since the last class. I filled out some of the sheets you gave us last time, Roger, but for some reason, I just seem to be”—and here she looked up at the group—“blocked.”

Roger nodded encouragingly. “It’s amazing how much this kind of research can be like a creative undertaking, and of course you hit creative blocks. Partially because you’re not just digging for information, you’re trying to patch together a story.”

“Yes, and I can’t tell you how much I’ve dreamed that you would come back to me,” she said. “To us,” she added quickly, her voice catching. If she would have laughed then, Roger could have seen the whole thing blowing over, but instead she seemed to panic, and he felt certain that everyone in the room must know about what they’d done. He flushed and could not look in Jane’s or Thomas’s direction.

She spoke rapidly, now, glaring at her notebook, softening her voice to try to gain back control. She didn’t know her real parents; last time she’d spent the entire course investigating the ancestry of the people who’d adopted her when she was just three. Her real parents—

Claire burst into the room with the baby strapped to her chest. Taking this in, Roger had a thought: What had he done with Jane’s note? Where the hell had he put it?

“Is Malcolm here?” she said. Her lips quivered as she spoke.

A pulse of alarm moved through Roger. “What? Claire, what . . . ?”

She could not find Malcolm. He was lost.

“The window!” Jane cried. “Did he crawl out the window?”

“No,” Claire said, holding out a hand, as if pushing Jane away. “I looked. I looked! The door was open. I swear I fell asleep for just one minute while I was feeding the baby. I swear!” She was sobbing.

“The downstairs neighbors,” Thomas began, “maybe he went down—”

“No! They’re helping me search,” Claire said. “He’s gone. He’s gone!”

Thomas leapt up from his chair. “I’ll go to the police station,” he said, brushing by Roger.

“I’ll go see if any of the shopkeepers has seen him,” Jane said to the whole room, then she put her hand on Roger’s and added, “You don’t know French!”

“I know that,” Roger said, yanking his arm away as if she were diseased.

Everyone scrambled from the room to look; they all knew at least some French. Roger stood, numb and dumbfounded, but as the room emptied out, Claire delivered Roger a look so tinged with blame, scorn, and terror that he was physically jolted to move. He ran outside, through the gate, onto the street, then stopped, looking wildly each way. He’d taken Malcolm to the park behind the plaza, which was a small, fenced-in number with slides but no swings, which Malcolm had regretted. Maybe he’d wandered there? His heart battled on in his chest.

As he ran through the plaza, he saw students from the class rushing about as well, stopping to ask strangers at the outdoor tables and along the cobblestone streets. He felt a swelling of gratitude to these students, despite his terror. He thought of Malcolm, the way he would climb out of his bed some nights and curl against Roger in their bed, the way he’d never been able to imagine, once Malcolm was born, a world without him in it. Malcolm the physical form, those pudgy fists and legs stomping before the hallway mirror, and Malcolm the boy who would evolve into a beautiful adult, an adult with his own genealogical chart that would only meet Roger’s halfway. Now that boy, the one in the moment and the one in the future, was gone. Just like that. His teammate. His love.

This was what Roger had earned, his true reckoning. A hot nausea rose up in him, and he was headed for the next narrow alley, where he could safely vomit, when Jane approached him. She was holding Malcolm in a blanket in her arms. He was naked and dirt-smeared and, seeing his father, he smiled. Roger leaned in to take him from Jane, cradling him in his arms, crying, unconcerned by who saw him. He cradled Malcolm’s young, bare butt in his arms, and breathed in the smell of coconut baby shampoo, dirt, tears. Grateful to Jane, but indifferent to her at the same time—the weight of his son in his arms was the only matter he cared about right now. He found himself bouncing and swinging Malcolm lightly, as he’d done when he was an infant in need of comfort. But it comforted Roger now.

All the while, Jane spoke to him, breathless about how Malcolm had let himself out of the apartment, how he’d wandered down the street naked, how such-and-such famous author’s daughter, who lived as a recluse in the family flat, spotted him, brought him in and called the police. As she spoke, Jane moved toward Roger as if she would touch him, and he was so grateful to her, frankly, he could have kissed her on the mouth, but then her eyes flitted beyond him and changed shape. They widened, following something. It was Claire with Travis, running. She was crying, and he knew, squeezing Malcolm, exactly how she felt. In fact, no one but the two of them knew how it felt to see Malcolm in one piece, alive. He went to open his embrace to let Claire and baby Travis in, but she was blubbering and took Malcolm and buried her face in him, kissing him, holding him carefully so that he wasn’t crushing the baby.

“I want you gone,” she said.

Roger looked up. The life he knew singed at the edges and curled away.

“I want you gone,” she said again, but dear god, she was saying it to Jane.

Jane held up her hands, her mouth hard and twitching, and turned to walk away. Others from the class were keeping a distance, relieved, their hands steepled in front as if in prayer. Roger tried to read Claire’s eyes, but she was still crying, still kissing Malcolm, still ignoring Roger. It was possible, Roger thought, that she was angry with Jane about something altogether separate from him: the comment at the party, her reaction when she heard Malcolm was missing. Her superiority. Her childlessness.

“Baby,” he said, touching Claire’s shoulder. “Baby.”

She flashed her gray eyes at him then, and he could see that if she knew, she didn’t care right at this moment. Some things made you forget even the worst trespasses. Roger could be worthy of this grace; he would be. He pulled Claire and the baby closer, took Malcolm back in his arms, and all of them stood there together, stunned, huddled against a gradual chill.

About the Author

Andrea Dupree’s fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Virginia Quarterly Review, Valparaiso Fiction Review, Confrontation, Crab Creek Review, and elsewhere, and she recently won a MacDowell Fellowship for her novel-in-progress. She cofounded and codirects Lighthouse Writers Workshop, an independent literary center in Denver.