About the Feature

[Listen to the author read this story]

In 1977, the year I was to begin first grade, my parents decided to take me out of our local public elementary school, where I had attended kindergarten, and enroll me in an all-boys private school across town, in what was back then a fairly downtrodden neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The move, so far as I can remember, came on the heels of a few run-ins I’d had with some older, black kids in the schoolyard toward the end of the previous year (I want to say they took the cookies from my lunch), and so, at least as far as my mother was concerned, my physical safety was a factor in the decision. But my older brother had been moved into a private school two years earlier, when he was in fourth grade, and it’s almost certain that I would have eventually followed suit. Partly it had to do with the fact that the New York City public schools were crumbling under a broken state budget, and my parents, themselves proud products of the public education system, were no longer convinced those schools could provide us with a good education. And partly it had to do with the fact that my parents, who had gone on to graduate from Harvard Law School, understood firsthand the particular pleasures of attending a well-endowed institution. But mostly I think it had to do with the fact that this was what successful professionals in the city like my parents did: enrolled their children in good private schools, so they could get into good colleges and graduate schools and go on to get good, high-paying jobs.

Which is to say that, in the end, the decision probably had less to do with who I was than what my parents had become.

So while my father sometimes acted as though he resented the decision—as though my mother’s anxiety had somehow forced his hand, that had it been left to him, I (let alone, my brother) would have toughed it out in public school as he had done and been the better for it—I suspect that he, like our mother, took a lot of satisfaction, pride even, in knowing that he had done his part to set us safely on the path toward prosperity, success, and happiness.

***

The school was not just any private school, but one of the oldest, most competitive schools in the country, dating back some three hundred years to a time when its founders had to petition the London-based Society for the Propagation of the Gospel for funding. Once a church charity school, after the Revolution the school transformed itself into a college preparatory program modeled on the great English schools, like Harrow and Eaton, establishing a private endowment, easing its reliance on the Episcopal Church, adopting a new motto—“Labore et Virtue”—and, according to the reverend who gave the address at the school’s 150th anniversary celebration, dedicating itself to nothing less than the “rightful training of our rising youth, of our city’s and country’s coming rulers.” Though the four-story building housing the elementary school I would attend dated back a mere seventy-five years, one nonetheless felt as though he were entering an imposing vault of history and expectation.

I remember the apprehension with which I first walked through those wrought-iron gates, the heavy wooden doors, the arched entryway, and found myself standing in the Great Hall, with its high ceilings, its marble floors, its giant glass chandelier casting a gloomy yellow light against the dark corners of the windowless room. To the left stood the receptionist’s hulking wooden desk, beside which arose a broad marble staircase; before me, between two shallow staircases descending to the library, was a seating area with aged leather wing chairs and alumni magazines; to the right, past a series of glass display cases containing old trophies, basketballs, and yellowing, black and white photographs of unsmiling boys in knickers, stood two wooden doors that led to the administrative offices, including that of the headmaster with his bow tie, French cuffs, and wingtips, and a blonde admissions woman with whom I vaguely remember having an interview. At the far end of the hallway, a narrow doorway led to an anteroom through which one entered the small, silent chapel with its rows of wooden chairs, an altar and unlit candles, and a small, wooden cross; beyond the chapel’s entrance a larger, brighter hallway led to the “new” building housing the cafeteria, the middle and upper schools, the large chapel with its towering cross and wooden pews, and the school’s renowned athletic facilities—a six-lane pool and separate diving pool; a giant, turf-covered sports field; a large, modern gymnasium and a wrestling gym—all of which any tour surely included.

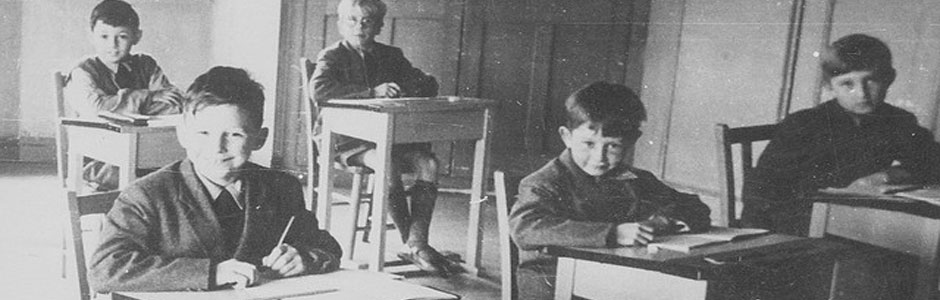

But what I remember most is being led back across the Great Hall and up that winding marble staircase with its wooden handrails worn smooth by the thousands of boys who had gone there before. I remember the leaded glass windows on each landing, and the boys in navy blue shirts on the second floor playing with the wooden blocks I loved (“Those are for the kindergarteners,” our guide noted to my profound disappointment). I remember peeking in the windows of classrooms where boys sat in neat rows of desks, science rooms with shiny lab tables, a music class where students solemnly played recorders beside a grand piano. And I remember how when we finally reached the top floor, home to the oldest boys in their neckties and blazers, I made the mistake of looking over the railing of the staircase, only to feel overcome with vertigo, as though at any moment I might tumble all those stories to the marble floor below.

***

I was, I confess, long before I entered the walls of that school building, an anxious, guilt-ridden boy, fragile in spirit, lacking in self-confidence, a boy who, not unlike his mother, saw danger lurking around every corner, in every unfamiliar face. I was easily overwhelmed, and it’s entirely possible, probable even, that any new environment was going to present something of a shock to my system. Yet when I think back to how wildly vulnerable I felt during those early weeks and months, I wonder whether I wasn’t responding to something particular to that school, a certain harshness or cruelty, even a subtle sort of violence that had little to do with me. For example, early on I developed a habit of calling out in class instead of raising my hand as was expected. Maybe I was excited to share my understanding or thought it somehow funny; maybe I just couldn’t contain all the anxiety I carried around. Whatever the case, it naturally began to irritate my teacher, who eventually created a system that involved marking down on index cards checks (on days I called out) or stars (on days I didn’t). If I received three checks during any given week, she would call my parents; if, however, I managed to keep quiet, I received a colorful (and, from my perspective, highly desirable) sticker.

From a certain vantage point this was a perfectly reasonable, even generous response to a boy who wouldn’t abide by the basic rules and expectations of the classroom, a response clearly aimed at giving me a stronger (and, undoubtedly, much-needed) sense of cause and effect. It was preferable to shouting at me, or throwing me out of the classroom, as other teachers might have done, or, for that matter, acting out her frustration in more subtle and potentially harmful ways. And, though it’s regrettable that my father would grow enraged with me when she called home, she was wise to enlist the support of my parents given the intractability of the problem and their obvious investment in my success. Indeed, compared to what was likely done at that school a generation or two earlier, with rulers and paddles and the like, I could be considered lucky.

And yet to me, there seemed so much vindictiveness in the way she went about the whole thing: how, whenever I called out again, her jaw seized, her face grew bright red, and she marched across the room to her desk, pulled out a note card, and made a checkmark with her ballpoint so emphatically I could hear the pen tip dig into the wood across the room.

It was as though she were going to stop me if it was the last thing she ever did.

Or consider the interactions among the students, a fairly ragtag, motley group, especially given the school’s distinguished roots. That is, while we were for the most part white, upper-middle-class boys whose parents could afford the sizable tuition, we were—unlike the boys of the country’s famous boarding schools, the Andovers and Exeters, from old-money families whose fathers and grandfathers had walked the halls before them—by and large first-generation private school students whose grandparents or, in some cases, parents had arrived in the country as poor immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and, especially, Eastern Europe (by some estimates half the school’s students were Jewish). And like any boys, we quickly seized on our differences, poking fun at one another—for being fat or short, or having a funny name or unusual way of speaking. Yet here, again, it was less the content than the tone of the exchanges that so unnerved me.

To take just one small example: During the early months of school, a boy who at various times I referred to as a “friend” began calling me a “skinny kike.” Maybe he knew an easy target when he saw one, though it’s possible I had provoked him; whatever the case, though I didn’t understand the real implications of the slur (and, to be fair, I suspect he didn’t either), he spoke it with palpable relish, and I felt ashamed. And whereas another boy might have hauled off on him and ended it (he was not so much bigger that this would have been impossible), or at least said something witty to shift the dynamics, I was neither inclined to fight nor confident in banter (and if it had occurred to me to tell my parents or teacher, I suspect I concluded I would somehow be implicated). Instead I suffered quietly, while trying to come up with a plan to stop him.

Finally, reasoning that (a) he’d been born in Rome and (b) no one liked to be called a “freak,” I decided to call him a “Roman freak.” (I don’t think I yet knew the term “wop,” though perhaps that would have been a more equitable response.) When I finally said it, however, it seemed to have exactly the opposite of the desired effect. “Skinny kike,” he said, a little more hatefully, and when another boy laughed, I regretted having said anything.

We were standing in the hallway outside our classroom, and I remember looking around as though for somewhere to hide. But other boys were watching expectantly now, and I sensed that if I didn’t do something, I’d be worse off than when I started. So, reluctantly, against my better judgment, I muttered it again—“Roman freak”—to which he promptly stepped closer still and responded —“Skinny kike”—with enough force that I winced.

I was not unacquainted with harsh exchanges: I routinely sparred with my brother, and my father didn’t hesitate to unleash his rage in my presence. But these were entrenched, long-term relationships with some context, some rhyme or reason, to their intensity. Yet I hardly knew this boy: How could he speak to me with such hatred? And it was this—my disbelief, more than any real desire to hurt him—that prompted me to keep lobbing the slur back.

No matter how many times I did, however, he returned it with a ferocity I can only describe as murderous.

***

I think it’s fair to say that even if I hadn’t been called a kike in first grade, I would have felt keenly aware of my “Jewishness” at that school. After all, even if half the boys were Jewish (and I suspect this claim was something of an exaggeration on the part of parents like mine who felt guilty about sending their boychiks to an Episcopalian school), I was the only one in our class who had a kosher home, who regularly attended shul, who brought to school his own kosher lunches wrapped in aluminum foil for Passover during the holiday. And while others attended Hebrew schools in the afternoons, none had fathers who served on their synagogue’s board, or regularly shared meals with their rabbis, or were as deeply involved in the day-to-day lives of their synagogues as we were.

Yet even a Jewish boy who didn’t identify with his religion couldn’t have helped feeling a little uneasy at a school where we were made to wear shirts with crosses stitched on them, where each week we filed across the Great Hall to the small chapel to listen to a reverend give sermons and benedictions, where once each year we marched down the long corridor to the new building for an all-school Christmas chapel that included an elaborate candlelight processional.

The hymns that began and ended services were especially troublesome for me, not simply because we were expected to sing them, but because the melodies were so lovely that I couldn’t have helped singing if I’d tried. No sooner had I been swept away by the music, however, than we would arrive at some phrase—“Jesus Christ, Our Savior” or “Mother, Mary of Christ”—and my body would seize. Did I stop singing and risk being noticed? Did I utter those words?

Though, like most ordeals at that school, I generally suffered with this one alone, I must have spoken my concerns on at least two occasions, once to a Jewish classmate, who told me he “mouthed those parts,” and once to my father, who declared simply, “Just don’t say it.” And perhaps for a stronger, more self-assured boy, such advice would have been useful.

But never in all my years at that school would the issue seem so simple.

***

It should come as no surprise that at a school such as ours sports, athleticism, and physicality quickly became the central organizing principle of its students, with the most athletic boys subtly and not so subtly wielding their prowess over the others on and off the field. Partly this was just a function of boys being boys in a place where no girls were present to soften the interactions. And, too, especially during those early years, with college applications at a distance, and little attention devoted to the arts, few alternatives existed for channeling our abundant energy. But, though our school was first and foremost an academic institution; though its athletic history was mediocre at best; though its varsity football program had been discontinued following a player’s death; and though the school had, so far as I know, produced only one world-class athlete, it maintained a nearly palpable belief in the value of physical education in “developing the country’s future leaders.”

To this end, we were early on introduced to regular physical education classes—wrestling, swimming, a variety of team sports—supervised by a humorless group of former athletes with varying claims to fame (one, for instance, had run a sub-four-minute mile; another had been an all-state wrestler) who herded us in our school-branded gym clothes to, depending on the activity, the small or large gym, the swimming pool, or the turf, not speaking so much as barking at us—to stay in line, to pass with more force, to spin out of an arm bar, to scramble up a rope—scolding us for our inattention, referring to us by our last names. Though athletic ability did not give you a free pass with them any more than it inured you against the teasing of other boys (I remember one boy in particular who was both strong and athletic but got teased mercilessly about the bowl-shaped haircuts he received from his mother), the best athletes undoubtedly avoided the brunt of their derision and frustration, teaching the rest of us that our destiny at that school would in no small part be determined by our success on the athletic field.

I was at a disadvantage in this environment, not only because I was skinny, prone to broken bones, fevers, sore throats, and rashes, but also because, in part due to my ailments, but also to the frantic efforts of my mother to fatten me up, I believed my body to be vulnerable and feared physical confrontations. And though I liked playing sports, I was not especially coordinated, and I had a terrible habit of flinching that hampered my efforts (and invited the jeers of my classmates). But I understood what was at stake, so I did what I could to make up for my inadequacies by, on the one hand, foisting myself into heated and ultimately doomed matches with superior athletes, and, on the other, distancing myself from boys with comparable or inferior skills by refusing to pass the ball, belittling their efforts, throwing an elbow—all of which made me a lightning rod for the frustration and even hatred of my classmates and teachers, who wasted no time in yanking me off the court and sitting me in the corner, face to the wall. Even unstructured recesses saw me desperately trying to establish my credibility: Instead of walking off with the other spastics to kick a ball, I would head to the pick-up football game, where I would wait in silent shame for a team captain to choose me (last), only to endure the humiliation of rarely if ever touching the ball. On those occasions when the ball was thrown to me, I was so surprised, so determined to prove my worth, I would almost invariably drop it, thereby solidifying my position in the order of things.

As is true with most of my struggles at that school, I’m inclined to blame myself for what I suffered on the playing field. Yet sometimes I can’t help wondering what my experience would have been like had winning and losing not seemed like a matter of life or death.

***

Years ago, I worked with a woman who told me how she spent a week at a Jamaican resort that was surrounded by such poverty and destitution that she hardly left the premises, not simply for fear she would be harmed, but because of the unease, the guilt and shame, she felt at having access to so much where most everyone else had so little. Though I couldn’t have articulated it back then, these exact feelings were an integral part of my experience attending that school, surrounded as it was by burnt-out buildings; graffiti-covered doorways; empty, overgrown lots. I remember being in first and second grade and hearing stories of older boys who had been mugged on their way home (and that was despite the volunteer parents in bright red ponchos patrolling the area); and we all knew that the “new” building had so few windows because it had been built during the race riots. And even less observant boys than I couldn’t fail to notice the faltering neighborhood on the van rides to and from school or, in later years, during morning lineups outside the gates.

Nowhere was the disparity more evident, however, than on the sprawling green turf that sat atop the single-story structure joining the old and new buildings. Some sixty yards in length, surrounded by chain-link twenty or thirty feet high, the field sat directly across the street from the stark concrete and steel yard of the local public school whose students were as dark as ours were light. What we must have seemed like to those kids—a bunch of a white boys carrying on in our blue shirts and pressed chinos behind that towering fence on our million-dollar sports field in the middle of their neighborhood. No wonder they mugged us! No wonder they shot bb’s or threw down from the surrounding buildings objects that could have killed someone! Sometimes someone—it might have been me—would get into a staring contest with some kids across the street, or shout something down; occasionally trash talk ensued, though of course the fact that we stood a full story above them rendered their words as impotent as stones cast against a castle’s ramparts. And I remember how afterward, intoxicated by our bravado, we’d run back into the safety of our building, laughing and carrying on as though we’d vanquished the enemy.

And maybe the others really felt that way. But I often felt so beset with guilt and fear that, left to my own devices, I might have run back out and begged for forgiveness.

***

So much seemed out of my control during those years, so much seemed beyond me. Even my own behavior seemed hopelessly out of reach. I can remember, for instance, in second grade telling a quiet Japanese boy with whom I had no grievance whatsoever that he had a “flat face.” And in third grade, I took another boy’s drawing, brought it to my lips, and pretended to tear it by making a whooshing sound with my mouth—only to realize I’d actually torn it in half. And more times than I can recall I antagonized a bigger, stronger boy, or called out another answer in class—even before I realized what I’d done. Even when I considered the consequences beforehand, even when I imagined the retaliation from classmates, the calls home to my parents, my father’s fury—even when I told myself not to do something because of the trouble it would cause me—I often couldn’t stop myself, as was the case, for instance, in third grade, when I pulled the stool out from beneath another boy in science class, causing him to land hard on the floor. And I remember how immediately afterward I protested my innocence, insisting I hadn’t meant to do it, hadn’t even wanted to do it, and feeling genuinely befuddled when no one believed me. Because that’s how it really felt to me: as though I hadn’t even done it.

So disconnected did I feel from my actions that sometimes I was accused of doing things I had no recollection of doing. For example, one day in second grade, I allegedly stepped on the face of a boy who often bullied me, creating a dark bruise on his cheek. Yet, even moments afterward, I had no memory of doing so. More troubling still, in third grade, I was accused of stabbing a classmate (whom I actually liked) in the palm of his hand with my pencil. “What did you do?” my teacher shouted, as she tried to stanch the flow of blood.

“Nothing,” I said, stunned at the accusation. “I didn’t do anything.”

“It’s your pencil,” she said, and I certainly couldn’t argue with that.

“Well, but I didn’t mean to,” I muttered, struggling to make sense of it. “It was an accident.” And I remember how panicked I felt, not simply because of the heavy cost I would pay with my classmates and teachers, but because I was no longer sure whom or what to believe.

That winter I received my report card, which, though not without praise, had a line that by then had become a staple of every report since first grade: “Andrew lacks self-control.” And I have no doubt my teachers were right: I frequently acted with little regard for the consequences that might befall me or anyone else. Yet had you asked me, had I been able to articulate it, I might have told you it wasn’t me but everything around me that was out of control.

And even now, some thirty years later, I’m not sure I would have been entirely wrong.

***

There were, of course, during those years, amid the chaos and conflicts and anxiety, moments of connection, softness, order, even genuine pleasure. I have, for instance, a fond memory of my first-grade birthday party at a local bowling alley, and of several pleasant if short-lived friendships with boys from my first- and second-grade classes, as well as the beginnings of a friendship with a Hispanic boy I remain friends with to this day. I remember spending many fun afternoons at the apartment of the boy who called me a kike, and the high-fives I received after catching a touchdown pass during a football game on the turf, and the quiet hush that fell over our fourth-grade classroom when our teacher informed us that one boy’s father had died. And I remember the perfect white teeth and high, pink cheeks of our school nurse, whose hand on my forehead I eagerly looked forward to during my frequent visits to her office.

By far my greatest source of comfort during those years, however, was my best friend, Mitchell, a pudgy, handsome boy who lived down the hall from us; a boy I had known since I was old enough to know anyone; a boy who was one grade below me at that school and whose lack of coordination, general distaste for school, and awful stutter undoubtedly left him feeling as dislocated as me. Though, in the perverse way these things work, his shortcomings kept us at a distance while at school (he was simply too much of a liability to be associated with), back in the safety of our building, I clung to him like a brother during a storm.

Even from an early age, Mitchell and I were allowed to come and go between each other’s apartments with relative freedom, and we spent countless afternoons together, playing knock hockey, kicking a ball in the hallway, playing handball in front of the building, spying on the girls from the girls school next door, and throwing all manner of food from our building’s rooftop. Mitchell was someone I could confess to without fearing his wrath or shame. And though occasionally our friendship ran aground, compared to the rifts with boys at school or, for that matter, the blow-ups at home, those with Mitchell were relatively harmless and short-lived; we cared too much about each other to remain angry for long, and I, for one, couldn’t have afforded to stay angry even if I had wanted to. He was, after all, the one person in the world in whose presence I consistently felt something resembling my self.

***

One reason my parents sent me to such a rigorous school (instead of, say, one of the city’s many average private schools like the one my brother attended) was that I was diligent, thoughtful, and highly self-motivated. I had an obvious aptitude for and interest in learning, and I was able to concentrate for long periods of time. When set up with a project with clear directions and a tangible goal, I took an almost obsessive approach to completing it, refusing to take a break until I had. In short, despite my anxiety, or, perhaps, because of it, I seemed more than capable of the high caliber of work that school demanded.

And for a while I managed to do just that. Though my behavior in class left something to be desired, once I arrived home, I immediately opened my book bag, sat at my desk, and set to work, making flash cards, practicing penmanship, memorizing math tables, and generally doing what was necessary to master the material I was expected to learn. And I enjoyed it: the learning process brought me a unique pleasure, a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment, even a rare feeling of control. But in fourth grade something changed. Though we’d always had assessments of one sort or another—though we’d long known that our academic performance was akin to Fate—that year we began to receive actual grades, and, confronted by this added pressure, I began to unravel. I can remember the awful dread I felt whenever our teacher announced a test; how I would study for days in a panicked frenzy and lie awake the night before worrying about what I still didn’t know; how I would sit during the test, leg shaking, changing my answers so many times the paper would tear; how, immediately afterward, I would curse myself for the mistakes I had made. To add insult to injury, I would later discover that had I stuck with my original answers I would have done better. “You’re doing just fine,” my mother encouraged me, and my father tried, too, in his own way: “You can’t worry so much,” he said. “It’s just a test.” But things continued to spiral out of control, and before long I found myself in the leather chair of a child psychologist.

One could argue that my parents were ahead of the curve, enlightened, even, in their willingness to take such a step; after all, it wasn’t so commonplace then to send a struggling child for therapy. And especially for my father, who believed in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, this was a generous, even courageous move, even if I knew he considered it a “crutch.” What is more, my memories of the gray-haired, mustachioed man whom I visited each week for the remainder of the year suggest he was well intentioned, sympathetic, experienced, a man who made every effort to engage me in the process and address what he reasonably referred to as the “personal problems that jeopardized my performance” at that school. Yet it strikes me as a little odd that never once in all our discussions together did we talk about the possibility that that school was somehow failing me, only that I was failing at school.

Which might explain why, whenever I sat across the desk from him, I felt as though he were looking at me through the wrong end of a pair of binoculars.

***

The higher we climbed in that building, the more chaotic things seemed to become. In fifth grade the relative calm of homerooms was replaced by a revolving door of new classrooms and teachers and expectations, and our small, fairly predictable physical education classes were upended by the addition of the raucous sixth-graders. What had in the past been primarily verbal confrontations increasingly became physical ones, and even lighthearted interactions routinely involved headlocks, noogies, hip-checks, and hard slaps on the head. Our teachers, once capable of commanding our respect or, at least, attention, became the objects of our hostility, derision, and threats, and any unstructured moment—climbing the stairs, walking between classes, lineups outside of school—saw an eruption of unbridled chaos. Even walking into the bathroom was something of a free-for-all, as you were liable to get bombed with toilet paper or shoved into the urinal while you were simply trying to relieve yourself.

It wasn’t like the school was easing up on us. On the contrary, each year the rules grew more rigid, the expectations more imposing, the consequences more severe. In fifth grade, our polo shirts were replaced by jackets and ties, and our female teachers were replaced by males. Bells began to blare, compelling us to race between classes or be marked late, and our grades, once mere indicators of our understanding, now “counted.” Our misdeeds were increasingly punishable by detentions, suspensions, and even expulsions. Though other boys may not have had fathers as unforgiving as my own, only the most senseless could have ignored the sensation of the walls closing in around us.

But the more intense the pressures grew, the more frantic we became. In the fall of fifth grade, someone—we never found out who—sent the heavy leather briefcase of an overweight, effeminate boy crashing down four flights of stairs to the floor of the Great Hall; that winter, a series of bomb threats forced us to stand outside in the freezing cold. The following year, one of my classmates tried to drown another in the swimming pool, and in the spring, one boy shot another in the face with a curtain hook, just missing his eye.

It was as though the rules were creating the very chaos they were instituted to contain.

And, increasingly, I lost my sense of where that school ended and I myself began.

Then one morning in sixth grade, my science teacher, a short, bookish man with thick glasses and hard leather shoes, asked me to stay after class. The previous day, after going over a test, I had informed him that he had mistakenly marked one of my answers wrong, and he’d promised to look at it. Now, as he led me across the room, I assumed he was going to give me the credit I deserved. Instead, he pointed to a microscope in the corner of his office, beneath which my test ominously sat. I glanced back at him for some clue as to what he had in store for me. “Go ahead,” he said, refusing to meet my gaze. “Take a look.”

I peered through the microscope at the brightly lit page of my test. “If you look closely,” he said behind me, “you’ll see your correct answer is on top of my red X.”

I could see what he meant but didn’t follow his logic. “I don’t understand,” I said, looking up again.

“Well,” he said, pushing up his glasses on his nose. “It would seem that you wrote the correct answer on top of my correction.”

I felt a sudden rush of heat to my face. “You mean, I cheated?” I said.

“Well,” he said, awkwardly, “I’m not sure what other explanation there could be.”

I remember having the overwhelming urge to protest, to defend myself, to tell him I hadn’t cheated and never would. I did nothing wrong! I wanted to shout. But I couldn’t bring myself to say anything; it was as though I were physically incapacitated. Don’t just stand there, I told myself. Say something! But the longer I stood there, the less sure I was what I would even say: Maybe he was right. Maybe I had cheated. How else could I explain the marks on the test?

So instead I turned and, without a word, walked out of the room.

It was mid-morning, second bell had rung, and the hallways were quiet. As I made my way up the back stairs to my next class, a profound exhaustion settled over me. It occurred to me that I should hurry, or at least go back and get a late note from my science teacher. But I just continued to walk up the stairs, slowly, listlessly, as though I had nowhere in the world to be.

At one point two boys burst through the third-floor doorway, laughing and carrying on, and one of them shouted something in my face. I didn’t even startle; I just kept climbing, one step after another, listening to their laughter disappear down the stairwell. Then all that remained was the quiet scuffing of my own footsteps, though soon those vanished, too, and I was left with a feeling like none I’d ever experienced before. It was a feeling at once troubling but also, somehow, exhilarating. Not numbness, exactly, or emptiness, or even loss.

It was instead the feeling of being swallowed whole.

***

In my basement closet, in the home where I live with my wife and sons, sit twelve navy blue yearbooks, one for each year I attended that school. Each is embossed with a golden shield bearing a cross and the words “Labore et Virtue.” More than once in recent months it occurred to me to consult them to help me understand what really happened at that school. But, inevitably, I found excuses not to. Though my middle and high school years were less tumultuous than my early years—though eventually I began to find a place for myself at that school—the pain of those early years sat hard inside me, and I suppose I felt reluctant to confront it so nakedly again. But I also didn’t like the idea that I was hiding from that school—that somehow it still had power over me all these years later. So, one afternoon, despite my misgivings, I dusted them off.

I don’t know what I was expecting to happen: An outpouring of grief? An eruption of anger? A torrent of shame? Maybe I feared those pages would somehow reach up and swallow me all over again. Yet, as I flipped through their yellowing pages, studying the photographs of faculty seated in their offices, boys at play on the turf, classes lined up in front of the school, as I looked at myself smiling no more or less awkwardly than the other boys and identified my classmates and read through their handwritten notes (“Thanks for a fun year”), I couldn’t help thinking that it all seemed rather, well, harmless.

Yearbooks, I know, present sentimental portraits of their institutions; indeed, the whole reason they exist is to project favorable images to the world, to encourage alumnae to dig into their wallets. And this alone might account for why I felt the way I did.

Yet, as I returned them to their shelves, I couldn’t help wondering whether I was making something out of nothing.

***

How can we rescue the truth of our experiences from the distortions of memory? How can we peel back our feelings about the past so we can discover the realities lying beneath? Not long ago, while visiting with an old friend—a boy with whom, though we’d attended that school together for twelve years, I became close only after graduation—I asked him whether he thought my impression of that school as somehow harsh or punitive was unwarranted. To be fair, he was from the beginning far more popular than I, a better athlete, more successful academically, more well-liked by our teachers—which is to say, his experience at that school was vastly different from my own. But he’s levelheaded and honest; he’s not, so far as I know, wedded to any particular perspective about that school; and I trust him deeply. “I don’t know,” he said thoughtfully, and already I felt again like a young boy being unfairly blamed for his problems. “People were pretty nice when my father died.”

“Well, sure,” I said, trying not to sound defensive. “But I’m talking more generally, about the daily interactions, in the classroom, among the students.”

“Maybe it was a little harsh,” he admitted. “But, I mean, we got a great education.”

“A great education?” I said, bristling at a phrase my parents might have used. “What does that even mean: a great education?”

“Well, it means we learned to think, to formulate arguments, to write—”

“Anyone can learn to write,” I interrupted.

“Not really,” he said. “Not well. Besides, look at you, look at me, look at our classmates. You know how smart the kids are from our graduating class?”

“What, because they aced their SATs? Because they got into Ivy League schools?”

“Well—”

“What about our inner lives?” I said, and even I was startled by how forcefully I spoke. “What about our selves?” And though I knew better than to keep going, I couldn’t have stopped myself if I’d tried: “That school didn’t do a fucking thing to help me understand who I am.”

In the awkward moments to follow, all I could hear was the sound of my own heavy breathing, and I remember how ashamed and confused I felt for having betrayed more than I’d intended—more than I’d even realized was inside me to betray.

“I see what you mean,” my friend said, breaking the silence. “You’re probably right.”

But I couldn’t be sure whether he actually agreed with me or was just wisely stepping out of an argument he saw he couldn’t win.

***

Why had I reacted so strongly? Why had I gotten so upset about experiences that had occurred more than thirty years earlier? Why this fierce, almost primal insistence that that school had wronged me? I mean, even if the school had somehow caused some me harm—and, really, the worst that could be said is that it had turned a blind eye toward my vulnerabilities, that perhaps it had tried to turn me into something I was not—the damage had hardly been irreversible or even, for that matter, long-lasting. On the contrary, the life I live now, in Portland with my wife and sons, writing and teaching and taking care of our home, is as meaningful a life—as much my own life—as any I can imagine.

If I really wanted to assign blame for what I experienced at that school, wouldn’t it more reasonable to blame my parents, not for sending me there (they were, alas, typical in this regard) but for doing so little to support me once I arrived? After all, had my father been less volatile, less inclined to blame me for my struggles; had my mother been able to see me through her worries about me; had they, together, created a more nurturing home environment, surely I would have had a stronger sense of self that would have allowed me to meet the challenges of that school instead of crumbling before them.

At the least, they might have seen the school wasn’t for me and found a better match.

And yet, the sad truth is, no matter which way I point the finger, I can’t help feeling that, when all is said and done, what happened at that school was all my fault.

***

Children are notorious for seeing the world as an either/or proposition—mine/yours black/white, right/wrong, good/evil. One could even argue that a large part of growing up is discovering that most things, in fact, fall somewhere in between. Probably, the safest, most truthful thing to say is that it was just a bad match; like any failed relationship, what I experienced at that school can, finally, be chalked up to bad chemistry. There were, alas, no evil players here, no malevolent forces, no one person or group or entity to finally hold accountable. On the contrary, everyone was probably just trying his or her or its best.

Yet part of me continues to resist this interpretation of events; part of me continues to go over it all in my mind; part of me continues to wander those hallways, defending, accusing, rationalizing, excusing.

It is as though some part of me believes it could somehow all still be different.

***

The stories we tell ourselves about the past invariably dictate our decisions for the future. In this light, it’s no surprise that I send my five-year-old son to a school where he is encouraged to play instead of perform, experience instead of memorize, cooperate instead of compete—a school dedicated (merely) to “nurturing the imagination, cultivating the intellect, and recognizing the spirit of each child.” And maybe one day he’ll accuse me of losing sight of him in the tangle of my reactions to the past. But if you want to know the truth: the relief I feel when I walk with him into school each morning is nothing short of exquisite.

About the Author

Andrew D. Cohen teaches English at Portland Community College in Portland, Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two sons. His essays have appeared in such journals as the Missouri Review, Confrontation, upstreet, the Saint Ann’s Review, and Hunger Mountain (as the winner of the Creative Nonfiction Award).