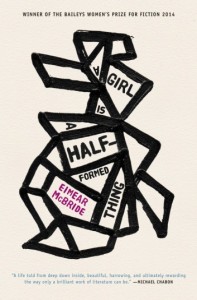

Book Review

With its staccato opening lines, Eimar McBride’s audacious and harrowing first novel, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, announces its linguistically disruptive intentions:

With its staccato opening lines, Eimar McBride’s audacious and harrowing first novel, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, announces its linguistically disruptive intentions:

For you. You’ll soon. You’ll give her name. In the stitches of her skin she’ll wear your say. Mammy me? Yes you. Bounce the bed, I’d say. I’ll say that’s what you did. Then lay you down. They cut you round. Wait and hour and day.

Though the themes—absent father, devout and overburdened mother, wayward daughter, sexual predation and religion—are familiar Irish literary territory, the book’s unnamed first-person narrator remaps it using sentence scraps, orphaned clauses, neologisms, and misspellings. It can be daunting reading initially, but the book’s rhythm rapidly asserts itself, and a liberating awareness sets in: it is not essential, or even possible, to always know what is happening, and yet on a visceral level, we understand. Ultimately the novel’s style reframes our expectations of prose and clarifies an urgent reality: we are all half-formed, to some degree.

Those first two words of the book—“For you”—introduce the narrator’s brother, who will remain a second-person pronoun, as names in the narrator’s world, including her own and those of places, are largely omitted. McBride uses this anonymity to limit our sense of the narrator’s formation and of the book’s setting; ultimately we wander the same unmapped physical, mental (and literary) Ireland the narrator does. A landmark that is named, though not immediately, is the brain tumor that struck the brother in childhood. Though treated with surgery, it remains a physical and metaphorical threat:

Listen to doctor chat . . . It’s all through his brain like the roots of trees . . . He’s running out I’m afraid. I’m afraid he’s running down . . . He’s not. He is. Can’t you operate again? We can’t. Shush. Something?

The tumor is all through the family as well: the father departs, and the mother’s responses to difficulty alternate between affection and abuse. The tumor affects the brother’s appearance and behavior, and he is ridiculed by schoolmates: “I know they have you off down there. That you’ll be butt and crib of jokes.” The narrator feels his humiliation as if it is her own: “It empties me. Throws me out. Dirty water. Dirty cup. I think for moment I’d rescue you.” Her empathy for him, central to the novel, never abates and in fact intensifies and shape-shifts into extremes of behavior and thought that McBride writes with unflinching realism. It makes for troubling and yet essential prose.

Catholicism offers morality to the narrator, but only through agents such as a manipulative grandfather, a mother who might either pray or deal vicious blows, and the well-meant but toxic intrusions of devout do-gooders. The narrator responds with contempt toward and rejection of God, but she cannot escape fear of punishment, such as when she is thirteen and her sexuality awakens: “What is it? Like a nosebleed. Like a freezing pain . . . What? Is lust it? That’s it. The first splinter. I. Give in scared. If I would. Stop. Him. Is a mortal mortal sin.” The “him” is her uncle, with whom she begins a sexual relationship that both repulses and allures her. There will be a great many other men after him, and for the narrator, sex is always an amalgam of relief, weapon, and burden. The book’s sexual episodes can be alarming reading, and yet these profoundly brutal scenes, such as when the narrator demands her uncle physically hurt her, demonstrate the novel’s unerring unity of form and content:

Alright slaps my face. That’s all I’ll manage. Some more than. Please. Take off my clothes. Stand in front I of him bare . . . More. He hits hard. I say don’t be done . . . I don’t want this he says I don’t want. Just till my nose bleeds and that will be enough . . . so he hits til I fall over . . . Jesus he says. I feel sick. But I’m rush with feeling.

We look directly at atrocity, but through a fractured screen of prose that both protects and terrifies us. If we have not already realized it, such scenes make it clear the narrative could not have been rendered in any other way.

McBride’s nationality, as well as her literary originality, have invited reviewers to invoke Joyce. The comparison is apt: McBride told the Guardian that when she first encountered Ulysses, she declared, “everything I have written before is rubbish, and today is the beginning of something else.” Her “something else” is a book whose linguistic athleticism is as essential to its design as multiple voices, metafiction, and mythic infrastructure are to Ulysses’s Dublin.

There are rare moments in McBride’s novel where the difficulty of sustaining her formal innovation seems to show through—later scenes, for instance, in which one may wonder why the narrator’s diction seems little changed as she nears twenty, and the end of the novel targets its conclusion with a certainty that feels predetermined. Neither tendency, however, diminishes the excellence of the novel, because the ending, like the prose, does its job with an air of singular purpose: no other finish and no alternate style could be substituted without degrading the whole. The result is that elusive quality of utter originality. Rereading this remarkable and brilliant novel a week, a month, or a decade after one’s first encounter will be no less an experience of discovery than it was the first time.

About the Reviewer

Geoff Kronik lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, and has an MFA from Warren Wilson College. His fiction and essays have appeared in Salamander, the Boston Globe, SmokeLong Quarterly, the Common, and elsewhere