Book Review

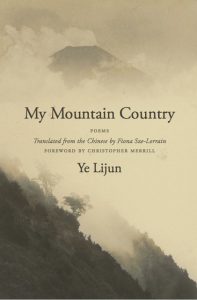

In the delightful collection of poems My Mountain Country by the Chinese poet Ye Lejun (which Fiona Sze-Lorrain vividly translates), readers encounter wutongs, peach trees, jackdaws, and ponkans; and to complement the heavy dose of natural scenery, we bump against oblivion, the clamor of the flesh, and healing without end. The strong presence of mountains (Mount Jiuyao, Snow Lotus Peak, Mount Yuhuang, Mount Nanping) always seems to bump against the misty abstraction of strong emotion. The gorgeous cover strikes the first note of the theme: a traditional mountain landscape with steep inclines nestled in a white fog with a couple of trees breaking the lines and reminding us we are a mix of our roots, dug into the earth, and our branches reaching into mystery and the eternal.

Often the lush vision of fir forests and autumnal leaves evince tranquility, but few of the poems stay settled. In “Full Moon,” for example, we are introduced to the “galactic disc” of the moon, lulling us, and then jarred awake—“Yet among mountains / I prowl each night.” Also juxtaposed are the impulse to tell a story and the need to reflect on meaning. “One day, in the courtyard in my green brick house,” begins “Realgar.”

The narrator seems consistently in search of where the “I” in the poems fits into the universality of natural experience—even when the natural experience include cities and others. “Where is my place?” The poems seem to ask—and, “Do I belong and how?” In the superb “Wandering in July,” the narrator’s restless need to understand and feel accepted is reflected in the animal voices she hears and the poem’s transfiguration of those into human voices:

. . . I weep by the well late at night

listen to voices

of wild geese behind the mountain. Is what I pass by

some transient

eternity? I arrive again at this place, but am no longer

of that time . . . How’ve you been

How’ve you all been

The poem concludes with a gentle prayer for communion:

. . . May

my kin and friends

deep in the mountains

in my rootless body, continue to grow

safe and sound in the universe—

Watching a stormy sea, and especially the waves crashing in sequence, the speaker in “Song of Tremble” feels herself dissolve into the larger motion—“Devoured, like snow into sea”—but the narrator is not consumed: “You lead me to disappearance / and restore me, again in this deep blue.” The alternating crash and reforming of the waves becomes a metaphor for the poet’s interaction with the larger, mysterious world: “I feel so ashamed—O Lord / a life seems to begin / Disquiet is ambushed in the subtle bliss.”

“Wandering in July” begins with an external landscape but almost immediately moves to the interior, where the equal awe of how time and rhythms (from the seasons to the passage of birthdays) create both beauty and despair brushing against the human need to make sense of change; the poet wields a kind of divining rod, susceptible not to water but to the larger, awe-inspiring inscrutability of human experience, and the sensitive soul trembles with gratitude. Trembling is both a response to awe of greatness and to a slight breeze that raises the hair on our arms—we are vulnerable enough not only to sense but react.

The poems long to be intimate without being too personal, universal without being too global. We have plenty of beautiful details—names of cities, specific plants and foods—but even they seem to be larger, more abstract as if they are placeholders for big ideas rather than artifacts from a lived experience. We learn pieces about the central speaker’s experience: the father left, the brother tragically died in a car accident, and the mother grew into old age, resentful and angry. And a shadowy “you” haunts several of the poems—first with an intense romantic energy, then a long-distant desire separated by oceans and mountains, and finally an absent cipher of regret. Memory and memories dance around nearly every poem—how they can’t be reconciled in the present, how they shift as we age, and how they shape a matrix that impacts our behavior both for good and ill.

Perhaps the mother is most fully realized in her years of hard labor and poverty, but she, like the other people, is never named and barely made more real than her circumstances. Though several of the poems are narrative, a larger narrative of the speaker through time only loosely appears: she reflects on turning forty, meeting people from her past, interactions with her father, and various places she has lived, but the impulse to complete a story is submerged in investigation of the sublime and transcendent.

The poems don’t have to be narrative to be beautiful, of course, and the themes of within bind them in a woof-and-weave tapestry that reveal a soul struggling with their place in time’s eternal advancement, her place in the universal design, and the conflict between the draw of the city and the salve of nature. The speaker feels deeply and sees her experiences in the world as meaningful, a kind of education writ large. “Real learning does not begin at school,” they say in “Memories of a Small Town,” and, “I accept the limits of time,” in “Fragments of a Seasoned Stroller’s Soliloquy.”

Ye Lijun’s poems sometimes read like traditional love poems, but her lyrics are not always enjoined to a person but rather a larger, more abstract force like oblivion, a tree, or a snowstorm. As much as individual people, these grand and complex forces are lovers and provide a similar kind of consternation and joy, attraction and mystification. As a poet, she is situated in the tradition of those great wanderers who see themselves aging, see themselves amidst change, and wonder if being a part of natural cycles that repeat is an equal permanence to being more steadfast, like the moon, but ultimately the poet finds comfort in the connection and a resignation to the human position in time’s steady current: “I know / I can’t avoid winter, the coming snow,” she writes, but also, “what an incredible world” (“Autumn Deepens;” “Nest”). The mountain endures, but so does our climbing.

About the Reviewer

Kyle Torke is a teacher of writing and reading, and he has published in every major genre. His most recent books include Sunshine Falls, a collection of nonfiction essays, and Clementine the Rescue Dog children's books.