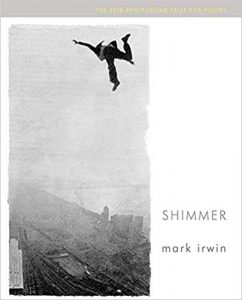

Book Review

Shimmer, winner of the 2018 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry, is Mark Irwin’s tenth collection. As one might imagine from the title, these are poems imbued with light: “light we smear / on faces and hands, then touch the far within one another,” and “Look, there’s snow / creeping down from the glacier and we’re blinking against / the bright light, opening door after door with a red knife.” Light wends through bodies and jars of marmalade. It seeps from doorjambs and device screens—and where this radiance permeates, darkness also gathers. “Sometimes the words are branches, recalling / saplings, then one day you’re older and realize that all the doors / are shadows,” and, “this world was built of praise where our bodies spoke, unlike these words / that sometimes cover up the white with a newer, stranger dark.”

Mortality’s shadow looms in many of Shimmer’s poems. The speaker mourns his mother while she lives and after she dies; he writes about other human losses, intimate and societal like those who perished in the 9/11 terrorist attacks; and he profoundly depicts environmental losses, species-specific and planetary. The collection opens with the poem “What a Great Responsibility.” Using anaphora, the speaker lists things no longer here, then lists other responsibilities—our use of language and our foreknowledge of death, and finally closes with an image of two kids that seems ordinary at first but turns toward the impossible:

What a great responsibility to think of things that no longer exists – the tree house

with ladder struck by lightning.

The skyscraper whose floors and ceilings collapsed as people dined above

while below computer terminals and desks flew out the windows.

What a great responsibility to think of creatures no longer here.

The Tasmanian tiger hunted to extinction, or the golden toad that burrowed

in the high cloud forests of Costa Rica.

And finally:

What a great responsibility to speak of things and people. This boy pulling

on his father’s work-gloves, or that kid in April, dragging an old violin

through loose soil till the pear trees bud and flower in an instant.

Irwin favors repetition, extended metaphors, quick shifts and turns in time and subject, and Lorca or Celan-like surreal impossibilities to create reflections and recollections that are slow and quick simultaneously and bend the real toward the unreal. In “Domain,” many lines begin with “To”: “To be alive, to feel / pain – cold on the teeth,” and, “To find domain in beauty’s / ephemeral wave. / To climb a stair for nothing but to stare, / purposeless as a flashlight at noon.” He moves the reader quickly through different ways to experience the world via our senses. And then he writes, “Once we really moved through a landscape, but now the scenery / unrolls lush colors on a screen.” The screen is our new epistemology. What does it mean to have this kind of knowledge, but to have lost our knowledge of physically being in the world? What does that mean for rest of life on earth? The poem ends with a striking and frightening image:

I’m entering that one’s house now, where the dinner guests are no longer

at their seats but under the dark table, the young and old blowing

out candles, and now we’re taking big spoonfuls, handfuls of burnt

sugar and flour, and with eyes closed thrust them into each other’s mouth.

In “Emaciated white horse, still alive, dragged with a winch cable to be slaughtered…” and “Uniform,” Irwin makes the reader wince with his descriptions of everyday violence against people and animals. In “Emaciated,” the speaker watches a YouTube video of a horse being mercilessly killed: “Stop, I screamed, the long // parameters of that word. Stop, I said, till the horse / becomes a house for us all. We live inside the hide / of that archival tent the wind still bellows / wild.” “Uniform” begins with a veteran in a wheelchair screaming at a man in car “‘Com’on, hit me, God dammit, hit me,’ / and he hit my stopped Honda, again and again, blood on the one chrome / rail of his chair.” Next, the poem shifts to “Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh who – dressed in an orange gown, / doused with gasoline by ISIS – was placed in a steel cage and burned alive.” He places us inside the hide/house/cage where we cannot look away.

The houses in Irwin’s poems function as symbols of memory and longing. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes that rooms and houses “are psychological diagrams that guide writers and poets in their analysis of intimacy” and that within them “[s]omething unreal seeps into the reality of recollections that are on the borderline between our own personal history and an indefinite pre-history.” Irwin also contemplates how language, words and grammars mediate our emotions and experiences in the world. In “Herald,” a poem written after his mother has died, he writes:

I remember how guilty I felt

putting sunscreen on the day after you died. – Noon’s

glare off snow, bright seeds from the Big Bang. I should have

let it burn my face. How odd to speak

of you now, a name glittering off the tongue

into air. Better to speak orphaned words

not clothed in a suit of grammar

And later:

[What] I’m trying to say is that sometimes the wooden

door opens to deer, the deer toward the woods, and the woods

toward lumber that becomes a house again where you stand, holding

a shirt like a body, trying to wash the bloodstain out, its tiny waves

like lips or distant, sunset-hands.

Irwin’s poems are not despairing but, in their impossibility, and dreamy realness they are present in a way that mirrors our daily range of emotions as we move through this life. Shimmer’s lyrical beauty and uneasiness in portraying the self in relation to others and the world reminds me of why I first loved contemporary poetry.

About the Reviewer

Tracy Zeman's first book, Empire, recently won the New Measure Poetry Prize from Free Verse Editions. Her poems have appeared in Beloit Poetry Journal, Chicago Review, typo and other journals, and her books reviews have been published in Kenyon Review Online and Colorado Review. Zeman has earned residencies from the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artist Residency, and The Wild. She lives outside Detroit, Michigan with her husband and daughter.