Book Review

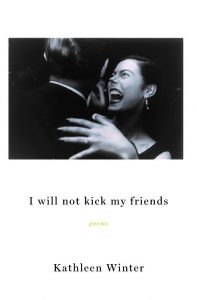

In “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James describes experience as “an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness and catching every air-borne particle in its tissue.” Kathleen Winter’s second full-length collection, I will not kick my friends, seems born of just such a sensibility—a consciousness shimmering with moments gleaned from the lives and work of dozens of artists, scientists, and literary figures, including James himself. Winter filters these moments through her imagination, and the result is a book of insight, written with precision and keen intelligence.

In “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James describes experience as “an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness and catching every air-borne particle in its tissue.” Kathleen Winter’s second full-length collection, I will not kick my friends, seems born of just such a sensibility—a consciousness shimmering with moments gleaned from the lives and work of dozens of artists, scientists, and literary figures, including James himself. Winter filters these moments through her imagination, and the result is a book of insight, written with precision and keen intelligence.

Jane Satterfield, who recognized I will not kick my friends with the 17th Annual Elixir Press Poetry Award, describes Winter’s work as “highly referential,” and indeed, allusions in nearly every poem will add layers of significance for some readers. However, one need not be familiar with the dignitaries whom Winter references to appreciate their role as inspiration for her poetry.

A line from Darcie Dennigan provides an epigraph for the first section, and introduces the id-like forces we see in the pieces that follow. Winter begins with Eve, first bullied by the serpent, then exasperated by Adam’s naivety. Next, the poet considers the strange allure of violent movies, the hubris of celebrities, and the risky precocity of teenagers. Her observations are clever, and often droll, as in “Screenplay for a Homemade Move,” a story of spouse-swapping in suburbia, with its wry “This is as romantic as Pleasanton gets.”

The second section of the book acknowledges an impressive roster of writers, including Katherine Mansfield, Jean Follain, Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, Olena Kalytiak Davis, and Brenda Hillman. However, it is Winter’s spiderweb in which these literary particles have been caught, and it is her sensibility, her voice, we hear throughout.

Winter holds degrees in both law and poetry, and her writing reflects the precision of language shared by those disciplines. Her vocabulary and syntax are well calculated for effect, as is her use of varied line length and space on the page—as we see in the title piece:

the longer you go the faster it went

sayitagain

say sound a shape speed liquefies

say sight a white mustache on sister’s lip

fish

lemons

ice

our eyelid aprons lead

towards night

Because of her facility with rhythm, assonance, and consonance, Winter’s poetry appeals to the ear, even as its brainy content engages the intellect. For example, “Letter from Iceland” notes:

I’m literal in the shadowbox sense

of the parlance diffuse and ruinous bliss

I’m Empress of Laxness I don’t want

to have complex ideas about flowers

The third section of the collection is dedicated to science, with appearances by Freud, Darwin, Feynman, Einstein, and assorted neuroscientists and mathematicians. Winter’s focus is never exclusive, however. She mixes physics with metaphysics and places science and art together; thus “Saints of Meta-Mathematics” closes with an allusion to Constable’s love of trees, and “Plague Saints,” about Remedios Varo, shows the artist as she “stares down a microscope.”

Saints appear throughout this book, but they are holy emissaries with pragmatic assignments. “Dreamland Saint” is asked to watch over the electorate. “Highly Sensitive Saint” checks scalps for lice. There is a saint for disobedient daughters, and one for solitary artists. “Picture Book of Saints” is a delightful litany that identifies, directly and by inference, many of the poems in the collection, and also pays homage to Winter’s influences, which, in the final section of the book, come from the world of art: still lifes, portraits, and landscapes, often examined through a characteristically epistemological lens.

Poetry born of a sharp intellect and distilled into sparse language runs the risk of being clinical, but Winter’s concern for the human spirit is evident, as in “Missing in the Louvre,” which describes an underrepresented population’s struggle to be seen:

One half of humanity

achingly

becoming recognized

as human

as human is a dark

and halting animal

ever possessive

of its own framed

place

in hallowed space.

Nor does Winter limit herself to mind and spirit. She engages the body through the senses: birds in “Rosemary, Pansies, Fennel, Columbines” are “singing in their Greek”; there are surging waves, bleating sheep, banjos; there are hints of arugula, olive, and lemon; and in “The Garden Party,” bourbon vanilla, egg, and even “leaves of grass / in sandwiches” appear. Sight and touch are invoked too, as in “The Grammar of Ornament”:

We shed slickers at the entrance,

before woodcuts of peasants,

bare-breasted. In a downstairs hall

Rome’s muscle glows on the torsos.

Besides Rome (and its muscle), the book’s itinerary includes Eden, Dubai, Provence, London, Iceland, and a guano-covered gannet sanctuary in Ireland. But these are merely external settings for internal journeys, as the speaker in “Luxembourg Gardens” describes: “Sparrows scurrying the garden’s gravel paths mapped / my mind’s traffic, ghost miners fossicking dead veins.”

Like the artists and scientists in her poems, Winter dreams and dissects. In “Tonic,” she notes, “the only way to learn / is hard ways,” and these poems are not always easy to access. But Winter balances insight with compassion, and reaches for the ineffable with humility and courage, so that her investigations become our own. So, when she writes in “Receptive Fields of Single Neurons in the Cat’s Striate Cortex”:

companions:

we have to get past being Man—

there are people so powerful

they go into war zones

and carry only cameras

it is not difficult to think of the poet herself in the role of potent witness.

About the Reviewer

Rebecca Patrascu lives in Sonoma County, California, and works at the local library. Her writing has appeared in Prairie Schooner, American Poetry Journal, Pinch (Literary Award winner, 2009), The Marin Poetry Center Anthology, and Digging Our Poetic Roots. She received an MFA from Pacific University and is the author of the chapbook Before Noon.