Book Review

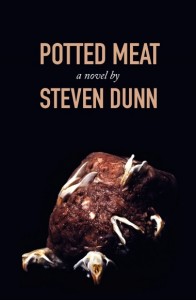

It’s likely that only a small fraction of Steven Dunn’s readers has actually eaten the food product that gives Potted Meat its title. Having tried it for myself recently, I can honestly say that this is probably for the best. In its most common form, potted meat combines salt, vinegar, sugar, and preservative chemicals like sodium nitrite, which prevents botulism, with a variety of “meat” or meat stuffs, including but not limited to beef stomachs, mechanically separated chicken, and what the label calls “partially defatted cooked pork fatty tissue,” which sounds like something the food industry invented to make potted meat sound healthier, as in, “Oh, it’s partially defatted—what a relief!” Mechanically separated chicken is no better, being the result of a process that mixes bone with muscle tissue, nerves, skin, bone marrow, and a few scraps of meat and then purees them all together before pushing them through a sieve that filters out the bone shards. This process results in a paste-like meat product, which is then fashioned into various foodstuffs, including everyday lunch meat. Texturally, potted meat it not unlike bad pâté. Try not to think about the taste.

It’s likely that only a small fraction of Steven Dunn’s readers has actually eaten the food product that gives Potted Meat its title. Having tried it for myself recently, I can honestly say that this is probably for the best. In its most common form, potted meat combines salt, vinegar, sugar, and preservative chemicals like sodium nitrite, which prevents botulism, with a variety of “meat” or meat stuffs, including but not limited to beef stomachs, mechanically separated chicken, and what the label calls “partially defatted cooked pork fatty tissue,” which sounds like something the food industry invented to make potted meat sound healthier, as in, “Oh, it’s partially defatted—what a relief!” Mechanically separated chicken is no better, being the result of a process that mixes bone with muscle tissue, nerves, skin, bone marrow, and a few scraps of meat and then purees them all together before pushing them through a sieve that filters out the bone shards. This process results in a paste-like meat product, which is then fashioned into various foodstuffs, including everyday lunch meat. Texturally, potted meat it not unlike bad pâté. Try not to think about the taste.

This isn’t to say that the book Potted Meat disappoints. Quite the contrary, in fact. Steven Dunn’s award-winning debut novel is a formally innovative, sonically distinctive work of art that offers its readers a rare glimpse into the lives of poor African Americans in West Virginia, where the novel’s narrator grows up. Instead of telling the story in a traditional, straightforward fashion, Dunn breaks up the book into three sections—1. Lift Tab, 2. Peel Back, and 3. Enjoy Contents—then further separates these into chapters (or ingredients). Where one might expect a table of contents, Dunn instead rewrites the label of a can of potted meat, exchanging ingredients like bone marrow and vinegar for “people hearts, rat turds, belts, church, coal, bats, flowers, dust, eyes,” and a slew of other unconventional ingredients of which the FDA would never officially approve. This dark, unflinching revision prepares readers for the often unpleasant, disgusting, heartbreaking, and odd scenes and characters in the novel. In one chapter, the family’s dog, Snow White, is locked in the basement, where it sleeps in its own piss and shit, which the narrator shovels once a week. In still another section, the narrator shoots, beheads, and then attempts to gut a groundhog. Potted Meat is not for those with weak stomachs.

Structurally, these three sections follow the narrator as he contends with poverty, puberty, racism, abusive parents, violence, alcoholism, drug dealing, social inequality, and a lack of opportunity that prevents him from pursuing his art or attending college. The first section, “1. Lift Tab,” presents a young (and still somewhat naïve) narrator who has yet to mature or fully understand his socioeconomic situation. He’s still a boy; he draws on his Etch A Sketch, has a crush on a girl whose family raises hogs. In the final chapter of the section, he’s outside pretending to be a ninja when he sees the body of a junkie with the needle still in the man’s arm. This stark image hits the reader like a slap in the face. Lifting the tab is equivalent to opening your eyes and finally seeing the reality of a situation. In “2. Peel Back,” Dunn strips away some of that youthful innocence—for there is innocence even in the violence of tearing apart lightning bugs and smearing their yellow, bioluminescent enzymes on your face—and shows the narrator struggling through puberty. He is caught masturbating in the bathroom, buys a present for his girlfriend, and lands a summer job as a garbage man. This second section ends with him getting high and having sex, like a teenager.

The third section, “3. Enjoy Contents,” is where the narrator begins to think critically about his circumstances and about the meaning of home, money, and death. In one heartbreaking—but still darkly comic—scene, his grandmother mistakes him variously for her dead husband or her eldest daughter. Family means a lot of things to him, including tenderness, lies, abuse, and neglect; he’s devoted enough to his grandmother to wipe her ass—and yet, when he hears the Gil Scott-Heron lyrics, “Home is where the hatred is / Home is filled with pain,” it strikes something inside him that wants to howl and scream. His family situation is holding him back, and he wants to escape West Virginia, but with his background and his mediocre performance in school, there aren’t many options for him to get out or attend college. His dream of becoming an architect seems utterly unattainable, not because he doesn’t have the skills (he’s actually a very talented designer), but because architecture school is too expensive. This is the reality with which he contends: because of his race and socioeconomic status, he’s statistically unlikely to pull himself out of poverty and get a college degree. Knowing this, he joins the Navy. It’s the best option available to him.

Nevertheless, in the final four chapters of the novel, the narrator questions whether or not it was the right decision. Each of these final four chapters is titled “Stay.” Stay. Stay. Stay, they read, as if they know something that the narrator doesn’t, as if simultaneously trying to remind him of the best parts of life in West Virginia and warn him of the dangers of leaving. Earlier in section three, the narrator and his grandmother sit, talking about death. It “happens in threes,” she says; because of this, the narrator tries to write a mathematical equation plotting death: y = 2x + 1, where x is both Death and ∞. Death is infinite. It’s all around him, lurking in everything and everyone, waiting until it can take him. But the equation isn’t perfect, he knows. It doesn’t account for the time, place, or manner of death. As he says, there are too many “unknown variables,” just as there are unknown, unappetizing ingredients in potted meat. In this light, the unconventional ingredients identified in the chapter titles are not just part of a recipe; they are instead those unknown variables that cause death and conspire to keep poor African Americans down, whether by feeding them unhealthy food or putting them in inadequate schools or limiting their job opportunities. Each chapter focuses on a small moment that illuminates these serious problems. Individual scenes may turn the stomach but, taken as a whole, Potted Meat offers readers powerful insights into what it means to be poor, black, and American.

About the Reviewer

Ruth Joffre graduated with an MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Kenyon Review, Mid-American Review, Prairie Schooner, Hayden's Ferry Review, Nashville Review, Copper Nickel, and SmokeLong Quarterly, among others. She also writes book reviews for The Millions and The Rumpus. She lives in Seattle, where she teaches at the Hugo House.