Book Review

We’ve come to expect a certain arc from the story of one who was sexually abused as a child by a family member. Perhaps dating from the burgeoning of the self-help industry in the 1980s, the story starts with the revelation of the traumatic event. Then confusion sets in for the victim. Did it really happen? Maybe it wasn’t a big deal. Should I come forward with this information? Flashback to the sometimes long period of silence when the victim, consciously or otherwise, tried to put the incidents behind her (it is usually—but not always—a girl). Once she feels comfortable enough to reveal the secret to a friend or family member, it quickly spreads through the clan, bringing new rounds of guilt, confusion, even recrimination. In the climax of this story—this part I remember distinctly from an episode of Roseanne—the victim confronts the assailant, a completion of the circle that started with these two alone in an entirely different power dynamic. Hence, redemption, transformation, a wrong righted. Run credits.

We’ve come to expect a certain arc from the story of one who was sexually abused as a child by a family member. Perhaps dating from the burgeoning of the self-help industry in the 1980s, the story starts with the revelation of the traumatic event. Then confusion sets in for the victim. Did it really happen? Maybe it wasn’t a big deal. Should I come forward with this information? Flashback to the sometimes long period of silence when the victim, consciously or otherwise, tried to put the incidents behind her (it is usually—but not always—a girl). Once she feels comfortable enough to reveal the secret to a friend or family member, it quickly spreads through the clan, bringing new rounds of guilt, confusion, even recrimination. In the climax of this story—this part I remember distinctly from an episode of Roseanne—the victim confronts the assailant, a completion of the circle that started with these two alone in an entirely different power dynamic. Hence, redemption, transformation, a wrong righted. Run credits.

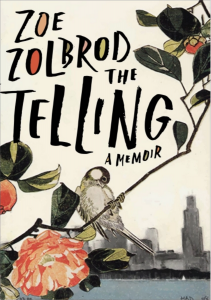

Some of this archetypal story exists in Zoe Zolbrod’s memoir The Telling—which reveals that Zolbrod was repeatedly molested as a five-year-old by her sixteen-year-old cousin Toshi—but something else in it is unique. There is a sense while reading that the simplicity of a rote recounting is exactly what Zolbrod doesn’t need, that its pat reassurances do her no good. Toshi abused her but also brought her an unexplainable bond at a young age, something nebulous she can’t quite pin down, that her “secret” with Toshi “was a secret from me even as I helped keep it.”

Growing up in Pennsylvania, Zolbrod came across similar abuse incidents in V.C. Andrews’s novels and The Color Purple, but she didn’t relate to them. “I still wasn’t quite sure what to look for,” she writes. “I wasn’t quite sure whether I qualified,” meaning as one traumatized by abuse. There’s a sense that for Zolbrod these cultural examples were more doors than windows.

Even more confusing is her reaction to Toshi himself, who as a cousin remained in her life. During college when Zolbrod was flirting with fringe activities like punk rock, drugs, and strip clubs, she chanced upon Toshi at her parents’ house and walked right by him, staring at her feet. “I was aware that I was pantomiming awkwardness and resentment at least as much as I was feeling it.” How much of her abuse history is genuinely damaging, and how much of it lends a twisted credibility to the “wild and lonely hunger to be real” she had at the time? As she finds her way through these possibilities, the mold of the canned abuse story breaks and something else emerges, both more genuine and perilous.

The remembered incidents bring mixed messages, as well. For example, as a five-year-old, despite her never wanting Toshi to come into her room at night, when the abuses occurred, Zolbrod admits, “I was intensely interested in what transpired.” Such admissions are the very epitome of our modern catchall “it’s complicated,” but how refreshing to have that cliché unpacked for once, revealing a fuller spectrum of human possibility.

The eventual revealing of the abuse to her father’s cousin Rebecca, a successful D.C. lawyer, is fraught with emotions that should be anathema, but Zolbrod, in her twenties at the time, can’t ignore them. Rebecca pries Zolbrod for information about the time when Toshi lived with her. Rebecca seems to know something, and Zolbrod does what she can to politely move the conversation past this uncomfortable topic. Finally, Zolbrod reveals the abuse to Rebecca, and afterward, being driven to a friend’s apartment, she writes, “I felt like a victim—less of Toshi than of Rebecca, that’s on whom I placed my blame. I do not say this lightly: I felt like I was being driven home from a party at which I’d been sexually assaulted.” This is the perfect example of how The Telling turns the abuse story on its ear. Rebecca would be crowned a hero for this type of coercion in many traditional narratives on the subject. As Zolbrod puts it bluntly later: “Pushy therapists, experts, telling a vulnerable woman that they knew more about her life and feelings than she did, especially if they could monetize her need for their truth? That was The Man all over, even if the therapist was a woman. And it was no good.” It’s one more convoluted truth for Zolbrod, but one that adds to her emerging sense of self.

Ultimately, abuse stories aren’t about confronting the perpetrator—though bonus points if he winds up in jail. They’re about the victim gaining authority over her own telling, what in the self-help language of the 1980s might be called coming to terms with one’s past. There’s clearly no single way to alight at this destination anymore than there is a single mode of abuse, or level of abuse, or kind of person. The reality of such trauma lies in its nuance to the individual, and The Telling bravely reveals Zolbrod’s own truth—not vindication over her assailant or some easy political score. It’s about charting genuine growth, the hard kind, because it all but can’t conform to type.

About the Reviewer

Art Edwards’s reviews have or will appear in Salon, Colorado Review, Entropy, the Rumpus, the Los Angeles Review, the Collagist, JMWW, Word Riot, Cigale Literary Magazine, and the Nervous Breakdown. His novel Badge (2014) was a finalist in the Pacific Northwest Writers Association's literary contest.