Book Review

When a German Gestapo officer pointed to a photograph of the painting Guernica, he asked Picasso, “Did you do that?” The artist famously replied, “No, you did.” A century later, Solmaz Sharif could offer the same response to the military-industrial complex of the United States with Look, her explosive first book of poetry. Instead of representing the devastating effects of carpet bombing a Basque town, Sharif embeds her verse with words and phrases from the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Such re-appropriation radically breaks the chains of signification behind the machinery of war that continues to so tragically define our nation, and, consequently, much of the Middle East. In “SAFE HOUSE,” each stanza (a poetic term derived from the Italian “room”), becomes more dangerous with language designed for our “SECURITY.” Ironically, attempting to “SANITIZE” discourse destabilizes the verse to which we’ve come in search of shelter.

When a German Gestapo officer pointed to a photograph of the painting Guernica, he asked Picasso, “Did you do that?” The artist famously replied, “No, you did.” A century later, Solmaz Sharif could offer the same response to the military-industrial complex of the United States with Look, her explosive first book of poetry. Instead of representing the devastating effects of carpet bombing a Basque town, Sharif embeds her verse with words and phrases from the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Such re-appropriation radically breaks the chains of signification behind the machinery of war that continues to so tragically define our nation, and, consequently, much of the Middle East. In “SAFE HOUSE,” each stanza (a poetic term derived from the Italian “room”), becomes more dangerous with language designed for our “SECURITY.” Ironically, attempting to “SANITIZE” discourse destabilizes the verse to which we’ve come in search of shelter.

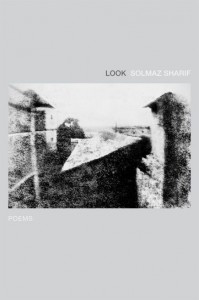

A book so attentive to meaning, which begins with a title poem declaring, “It matters what you call a thing,” warrants close attention to its name. In an age of countless unlimited poetry books, titles sometimes seem to be all that matter; at first glance Look appears insultingly easy and didactic. The imperative verb becomes a noun used by the military, however, when defined in epigraph: “In mine warfare, a period during which a mine circuit is receptive of an influence.” On the cover of Look is a copy of the first photograph ever taken, which charges the book with similar visual implications to tread carefully. A view of an estate from an upstairs window in the Burgundy region of France appears unrecognizable enough to both sustain and displace the gaze in a search of true origins. Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, cited such loss of the subject’s originating “aura” through photographic replication. Represented in black and white, this first photograph introduces a collection of poems that expose the inherent decadence of the symbolic by separating it from its forced martial referents.

While this clever approach sufficiently accounts for why Sharif has garnered multiple awards, considering it a mere conceptual project risks undermining her creative use of the self– as– Other to further interrogate the linguistic relation to hegemonic power. Standing outside of the Republican National Convention, in a poem of the same title, an unnamed man tells her that if he were from her native Iran, he would put up with “TORTURE.” Framed by legalistic clauses beginning with “Whereas,” the poem quickly turns to personal destruction: “Whereas years after they LOOK down from their jets and declare my mother’s Abadan block PROBABLY DESTROYED. . . .”

The sensibility that develops throughout this collection, like an early photograph, can perhaps best be considered “romantic postmodernism.” Contradictory impulses between poetry’s long tradition of preservation through image and the current trend of foregrounding symbolic decadence through documentary poetics inform much of the lyric tension. Rather than merely foreground thwarted meaning in playful yet limited acknowledgement of its loss, Sharif insists on the self’s interrogation of destabilized representation. Positivist intuition of the nineteenth century turns suspect and must suffer in its attempt to make sense of what can’t be fully recollected. In this respect, Look achieves Wallace Stevens’ critical standard of poetry by deftly responding to the true spirit of the time in which it is written. Following a list of military operations called “PERCEPTION MANAGEMENT,” a series titled “Personal Effects” begins to recall the poet’s uncle, preserved as image on her computer desktop, who died in the Iran-Iraq war. “This album is a STOP-LOSS,” declares the speaker, as though the perception of her uncle has been managed for us as readers cum viewers:

He suspends there

by STANDING ORDER,

a SPREADING FIRE in his chest,

his groin. He is on STAGE

for us to see him, see him?

He stands in the noontime sun.

Later in the series, with her uncle’s “PERSONAL EFFECTS” in “a white archival box,” the speaker declares, “I am attempting my own / myth-making.” Yet how can she? Her uncle’s body itself has become as commodified as the discourse she interrogates:

Daily I sit

with the language

they’ve made

of our language

to NEUTRALIZE

the CAPABILITY of LOW DOLLAR VALUE ITEMS

like you.

The effect of the personal, recollected in such essential fragmentation, defers and displaces clichéd elegiac grief. A few pages later (it is a long and rather extraordinary series, very much a kind of clinic on how to write one), the speaker aptly captures the lost moment, noting how “each photo is an absence, / a thing gone. . . .” An earlier series of letters as erasures written to a Guantánamo inmate who sadly can never reply dramatically marks a related absence.

The language of blurbs on the back of poetry collections, like the military diction Sharif leads us to question, has tragically been bled of its hyperbolic significance. Ordinarily, the seemingly impossibly high critical praise for this book would warrant critical debunking. Look, however, is no ordinary book. In this respect the usual adjectives with which it has been stamped—“beautiful,” important,” “distinguished,” “perfect”—seem to fall somewhat short in capturing its real essence. Crossing into such volatile aesthetic terrain charged with a radical decadence, this collection threatens even the relevance of such superlatives with obliteration. Quite possibly, it deserves to be called dangerous.

About the Reviewer

Roger Sedarat is the author of two poetry collections: Dear Regime: Letters to the Islamic Republic, which won Ohio UP’s 2007 Hollis Summers’ Prize, and Ghazal Games (Ohio UP, 2011). He teaches poetry and literary translation in the MFA Program at Queens College, City University of New York.